The Scandalous Flap Books of 16th-Century Venice

Cheeky pages revealed more than their drawings initially let on.

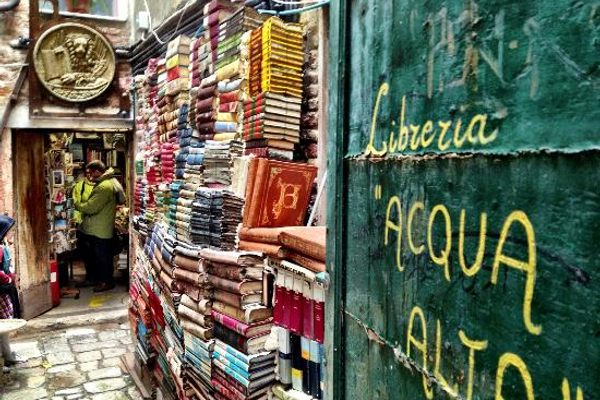

Imagine you were a rich European in the 16th century, and you wanted to travel. Top on your bucket list might be Venice, a cosmopolitan, free-wheeling city, known for its diversity, romance, and relaxed mores. Venice was a wealthy place, where Titian, Tintoretto, and other famous artists were at the height of their powers. As a republican port city, it was tolerant of all sorts of people and all sorts of behavior in ways that other European cities were not.

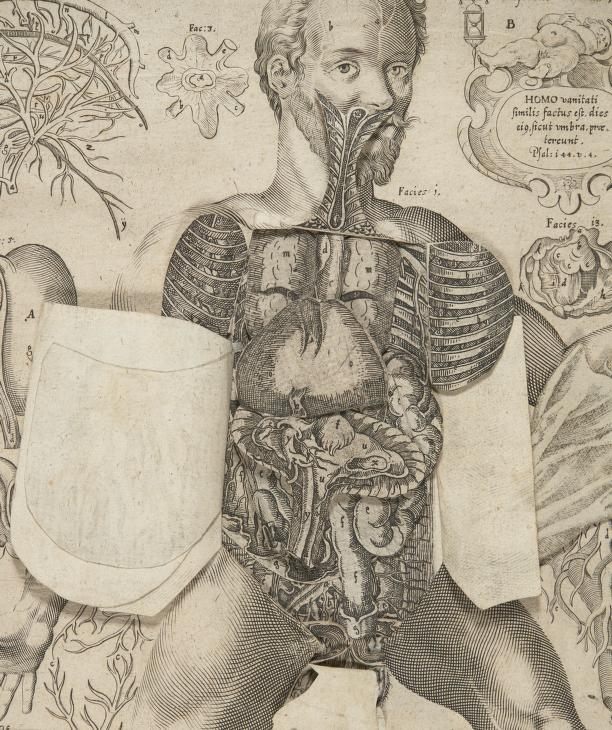

While in Venice, you might purchase a flap book to help you remember the good times you had there. Above is one example of an illustration from Le vere imagini et descritioni delle piv nobilli citta del mondo—“the true images and descriptions of the most noble city in the world.”

This image is part of a new exhibition at the New York Public Library, Love in Venice, which includes two flap books from the late 16th century that depict a lascivious kind of love.

The books are attributed to Donato Bertelli, a printmaker and bookseller, although it’s hard to say exactly who wrote the book. What is clear, says Madeleine Viljoen, the curator of the exhibit, is that the book is connected to “a family of very savvy book publishers who understood how to take advantage of people coming to Venice for tourism and people curious about what they might see there and experience there.”

In the 16th century, flap books were a fun innovation in publishing, used for purposes both serious and satirical. One of the most studied types of flap book displayed the anatomy of the human body: you could dissect a person by paging through the flaps. Publishers also would use layers of paper to create volvelles, wheels made of paper that might be used to calculate the movement of the sun or moon.

But there were also some cheekier uses of the flaps. During the Counterreformation, for instance, one flap book let the reader lift up the robes of Martin Luther and peek underneath. “I don’t think it was meant to be playful or titillating,” says Viljoen. “It’s about humiliation.”

Some of the images in the Venetian flap books have an edge to them, too. One shows a woman riding a donkey; flip the image up, and it’s revealed that she’s riding on the back of a man, an image meant, perhaps, to warn of the dangers of female power. There’s also another image of a woman with a flippable dress, but underneath this dress, there are only skeletal legs.

For the most part, though, flap books were supposed to be fun. Another image in the exhibition plays on the famous trope of a woman and her not-very-good chaperone:

“It’s meant to be playful and mischievous and point to why Venice was perceived as playground,” says Viljoen. “What went to Venice was left in Venice.”

To experience the playground of modern-day Venice, join Atlas Obscura on our July trip: Hidden Venice with a Psycho-Mambo Twist.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook