Up Close and Personal With the World’s Most Artistic Mollusks

Deep sea “carrier snails” painstakingly turn their shells into tiny dioramas.

Step into the Zymoglyphic Museum in Portland, Oregon, and you’re immediately surrounded by impossible creatures. One case holds a couple of Scaly Eyeball Plants, contorted and peering out of jugs, and a Pond-Headed Cactus, its crown like a miniature fishbowl. In another small tank, multicolored crabs hide in the sand, and clams disguise themselves with oversized sunglasses. Elsewhere, in a place of honor, the Zymoglyphic Mermaid rests on a spiky coral throne, her sharp beak pulled into a smile.

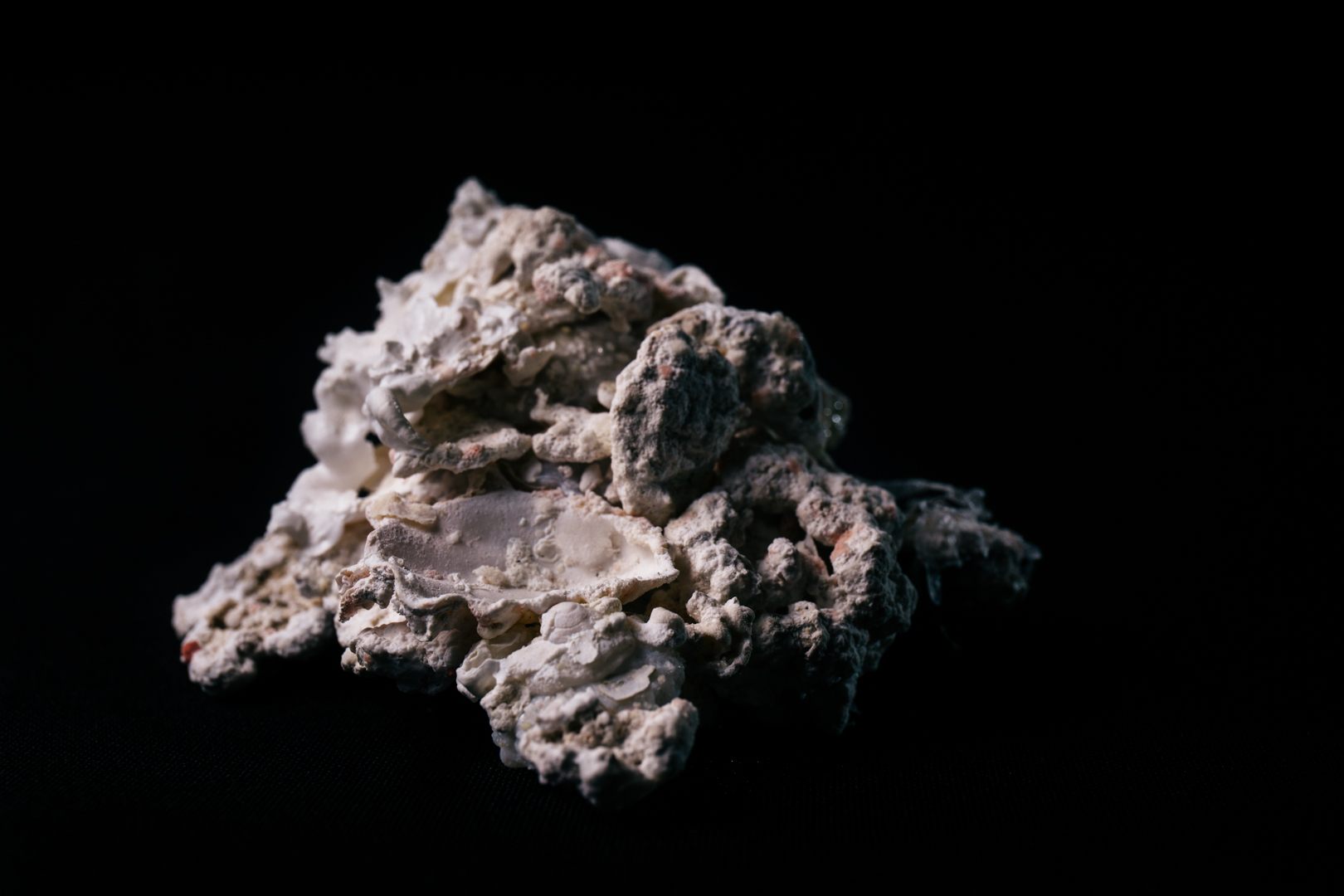

Wander over to the museum’s Xenophora Collection, and you’ll see about a dozen other strange specimens—this time, a collection of surprising snail shells. Each is like a miniature undersea mosaic, artfully covered in smaller shells, rocks, and bits of coral. Some have entire sponges growing out of them. One even sparkles with a spare bit of sea glass.

But as well as these shells fit in with their fanciful neighbors, there’s something a little different about them. The mermaid, eyeball plants, and other creatures are fictional constructions, built by a human artist as part of a constantly evolving, imagined world. But these impossible-looking shells are 100 percent natural. They are, indeed, shells from the genus Xenophora—artworks made by actual sea snails.

Jim Stewart, the creator, curator, and proprietor of the Zymoglyphic Museum, is always searching for objects that speak to him. As a child, he collected arrowheads, bird’s nests, leaves, and stamps, carefully labeling and arranging them. Later in life, he began to collage these odds and ends together, creating tiny, strange worlds—a yellow crab next to a miniature gravestone, or a creaky-looking rainforest, with rusty wires tangling like vines. “I got interested in surrealism, and how the juxtaposition of things can make a more meaningful connection,” Stewart says. “The objects take on a narrative.”

The Zymoglyphic Museum—the result of decades of similar efforts—purports to showcase creatures and artifacts from various fantastical, fictional eras that Stewart has dreamed up, like “The Rust Age” and “The Age of Wonder.” Just as ordinary items can, through combination, create drama and tension, the museum itself is a hodgepodge of visuals and ideas made even more meaningful by their proximity. These days, when Stewart is excited by a particular object, he tries to place it in an exhibit, fitting it into an existing diorama or making it the centerpiece of a new one.

When he came across his first Xenophora shell at a shop in Florida—where it stood out defiantly in a sea of smoother, pinker specimens—he felt something different: kinship. “The idea of animals that seemed like they were doing assemblage art, that was really appealing to me,” Stewart says. “They almost seem to have personalities.”

Xenophora have been around since the Upper Cretaceous, an era better known for bringing us the Tyrannosaurus Rex and covering the land with flowering plants. As such, the snails have spent millions of years refining their artistic process—which, it turns out, is somewhat similar to Stewart’s. As the malacologist W.F. Ponder explains in a 1983 paper, an individual snail will choose a particular object and lift it up, either with its foot or with its proboscis, a tentacle-like appendage that protrudes from the top of its head.

Once the snail has its newest decoration in a particular spot on its shoulder, it will cement it to its shell with goo from its mantle. Depending on the species, the snail might also take the time to clean its shell to make it ready for the new addition, or stuff sand and debris underneath it to make sure its sticks properly.

When the snail is younger and smaller, it sticks to proportionately smaller items. As it gets larger, though, it can handle bigger ones. Because mollusk shells grow in a spiral, the shell of a mature Xenophora serves as a miniature timeline of its life, with tiny souvenirs in the middle of its shell, and big ones on its outer whorls. Different species also tend to collect different things—as one expert, Kate St. Jean, details in a 1968 paper, Xenophora pallidula, of Japan, collects rocks, shells, and coral, while Xenophora peroniana, of Australia, generally sticks to just rocks.

These snails’ habits have earned them a number of monikers, from “antique collectors of the sea” to “underwater masters of bling.” (The name Xenophora is a nickname in itself—it’s Latin for “carrier of strangers.”) But although it may seem like they’re showing off, experts say they’re likely doing the opposite. “Everything they do seems to suggest means of eluding detection,” writes St. Jean. Rather than sliding across the ground like land snails, they tend to hop or stomp along, so as to not leave a trail. They even bury their feces, like cats.

Their self-decoration serves the same purpose. Predators lurking above may mistake a Xenophora for a particularly artful pile of debris. And even if they don’t, the prospect of chewing through extra rocks and shells may deter them from venturing a bite. “The Xenophora are the supreme camouflage artists of the mollusk world,” writes St. Jean. (They’re so good, in fact, that unsuspecting plants and animals sometimes grow on top of them—thus the sea sponges present on a couple of Stewart’s specimens.)

Those Xenophora who have ended up in the Zymoglyphic Museum are long dead. But even in their new environment, their camouflage remains effective. “A lot of people who come in assume that I put them together myself,” says Stewart. As all good collagers know, truth is occasionally stranger than fiction.

You can visit the Zymoglyphic Museum on Obscura Day, May 6, 2017, and see the Xenophora Collection for yourself—along with dozens of exhibits that are too good to be true.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook