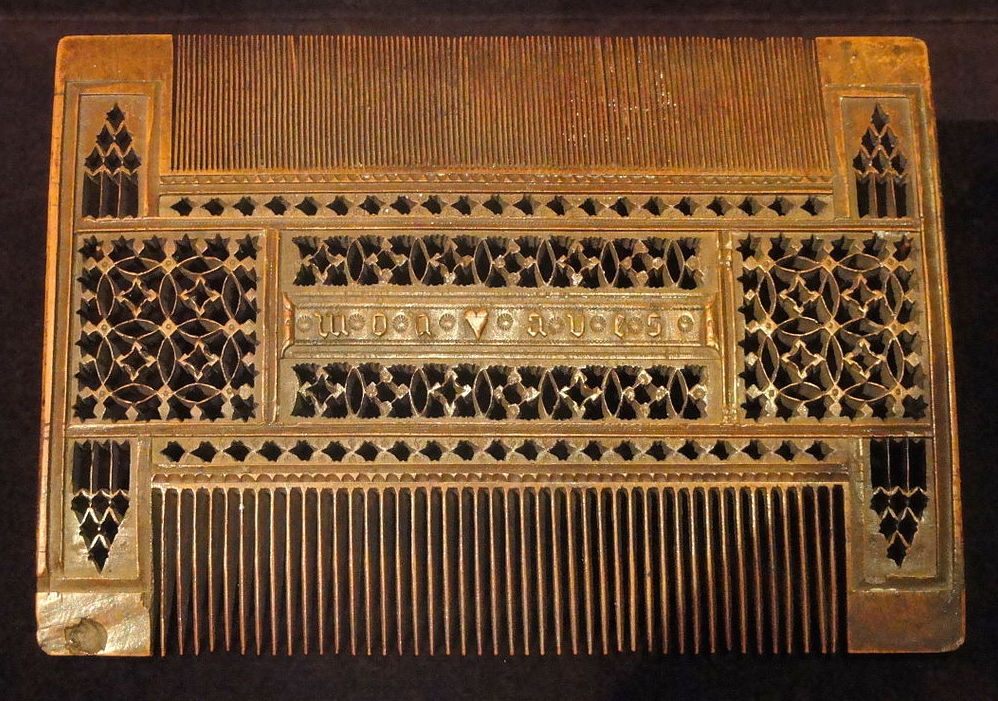

Some of History’s Most Beautiful Combs Were Made for Lice Removal

Delousing can be delightful.

A 19th-century de-lousing comb made in India. (Photo: Science Museum, London, Wellcome Images)

Thirty years ago, parasitologist Kostas Mumcuoglu and anthropologist Joseph Zias were examining a first-century hair comb excavated from the West Bank when they found a surprise lurking in its fine teeth: 10 head lice and 27 louse eggs.

With their “interest in lice having been aroused,” they later wrote, they began to look more closely at some other ancient combs that had recently been excavated. To their delight, eight of the 11 combs unearthed in the Judean Desert contained lice, eggs, or both.

The presence of these parasites was a major shake-up. “We had assumed that combs were used almost exclusively for cosmetic purposes,” they wrote in their report. “Now it appears that they were also used as de-lousing implements. Indeed, the combs we examined appear to have been designed specifically for de-lousing.”

A wooden comb from Egypt’s Coptic Period (500 A.D. to 1000 A.D.) (Photo: Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Public Domain)

Today, lice combs are a cheap, plastic affair, used in conjunction with chemical treatments to rid scalps of the schoolyard scourge. But historically—going all the way back to the Ancient Egyptians—combs incorporating de-lousing designs were used as daily implements.

“Most ancient combs are double-sided and have more teeth on one side than the other,” wrote Mumcuoglu and Zias. “The user would straighten his or her hair with the side that had the fewer teeth and then whisk away lice and louse eggs with the finer and more numerous teeth on the other side of the comb.”

This wooden comb was made in India during the 19th century. (Photo: Etnografiska Museet/CC BY 2.5)

Combs were most commonly made of wood, bone, or ivory, and often incorporated intricate carvings. In the medieval era, scenes of courtly love and Biblical piety were incorporated into the designs. But the double-comb layout, with very fine teeth on one side and sparser teeth on the other, has remained the same since antiquity.

The reason? It does the job so well. “[C]ombs found in archaeological excavations are artistically superior to, and at least as effective as, the ones we use today,” wrote Mumcuoglu and Zias.

In appreciation of the beautiful lice combs of yore, here is a sampling of the more striking designs.

This French wooden comb was made during the 15th century. (Photo: Daderot/Public Domain)

The openwork carvings in the French comb above, which dates to the 15th century, were inspired by Gothic windows. The inscription reads mon avis (meaning “my judgment”). The reverse is inscribed with pour bien (“for your comfort”). These phrases were printed on combs intended to be given as gifts between the intimately acquainted. Because nothing says love like a lice comb.

A French wooden comb from the 16th century. (Photo: Public Domain)

An even more intricately carved design followed in the 16th century.

A 12th-century Venetian ivory comb. (Photo: Walters Art Museum/Creative Commons)

The ivory comb above, from the 12th century, was made in Venice. It features two peacocks flanking a cheetah.

A comb with scenes of courtly life, from 15th-century Venice. (Photo: Walters Art Museum/Creative Commons)

The 15th-century ivory comb, above, shows, in the words of the Walters Art Museum, “typical pastimes of wealthy nobles.” These include dancing in a garden, playing a portable organ, and hunting deer. While most of the comb’s original paint has worn off, the gold on the hair of the figures remains intact.

A 14th-century ivory comb made in Paris. (Photo: Valerie McGlinchey/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Some medieval combs depicting Biblical scenes had a “liturgical function,” meaning they were swiped around the heads of bishops, priests, and kings prior to their ceremonial duties.

An Italian ivory comb from the 15th century. (Photo: Public Domain)

This Italian comb, made circa 1400, depicts the Adoration of the Magi. (Photo: Public Domain)

The ivory comb below, made in England in the 12th century, crams in not one but seven scenes from the Bible.

A 12th-century ivory liturgical comb made in England. (Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen/CC BY 2.5)

The V&A Museum, where it is held, notes that the corners depict ”The Nativity, The Flight into Egypt, Crucifixion and the Entombment, while the central space—on a larger scale—shows The Washing of the feet of the Disciples, The Last Supper (with only eight apostles) and the Betrayal.”

Not pictured are the four more scenes carved into the reverse side of this very intricate lice comb.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook