Text-To-Speech in 1846 Involved a Talking Robotic Head With Ringlets

Meet the Euphonia, a machine that boasted the ability to replicate human speech.

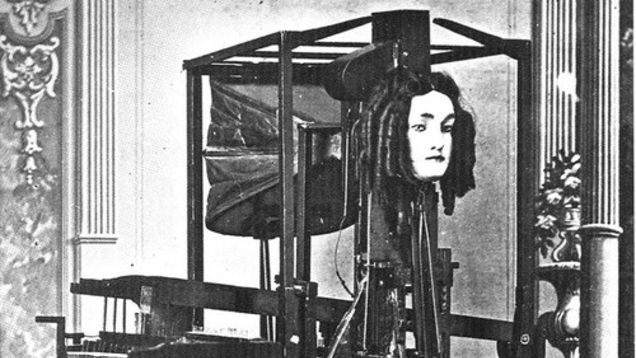

A close-up of the Euphonia. The Euphonia’s face was impressively realistic but was reported to look very unsettling while in motion. (Photo: Public Domain)

On a summer day in 1846 at London’s grand Egyptian Hall, Joseph Faber unveiled one of the strangest inventions to come out of the 19th century’s technological boom. For one shilling a head, spectators were ushered into a dimly lit back room to see the Euphonia, a machine that boasted the ability to replicate human speech.

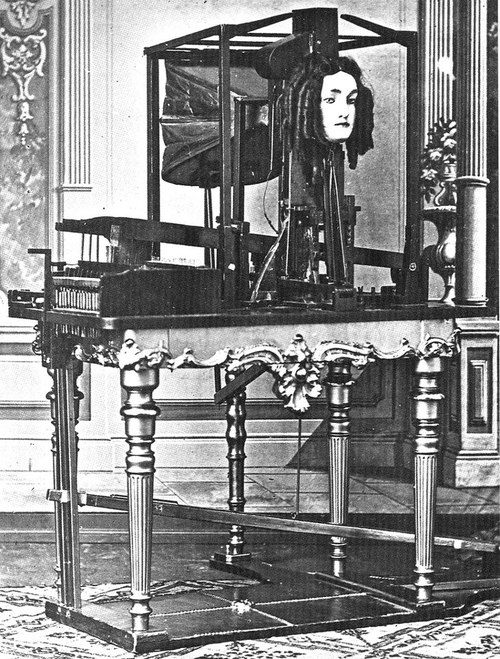

In the middle of the disheveled chamber sat a piano-like instrument topped with a female automaton whose face, framed with ringlet curls, stared vacantly into the crowd. Professor Faber, a shy German astronomer-turned-inventor, stood behind the keys of his device hoping desperately that the few people in attendance would be impressed by what he was about to show them.

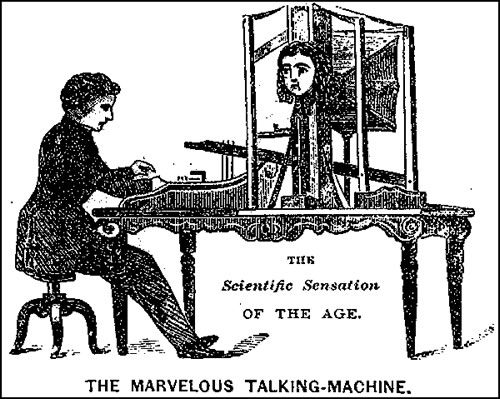

The Euphonia was the product of 25 years of research and an undeniably impressive feat of engineering. Fourteen piano keys controlled the articulation of the Euphonia’s jaw, lips, and tongue while the roles of the lungs and larynx were performed by a bellows and an ivory reed. The operator could adjust the pitch and accent of the Euphonia’s speech by turning a small screw or inserting a tube into its nose. It was reported that it took Faber seven long years simply to get his machine to correctly pronounce the letter e.

With a conviviality akin to 2001: A Space Odyssey’s HAL 9000 computer, the Euphonia began the exhibition at Egyptian Hall by saying: “Please excuse my slow pronunciation…Good morning, ladies and gentlemen....It is a warm day....It is a rainy day....Buon giorno, signori.” Spectators were then invited to ask the Euphonia to speak whatever words they wished in any European language. Faber then had the automaton sing a haunting rendition of “God Save the Queen” in celebration of its inaugural London show.

An advertisement for Faber’s “Marvelous Talking Machine,” later renamed “the Euphonia.” (Photo: Public Domain)

The crowd’s response to the Euphonia fell abysmally short of Faber’s expectations: the few people in attendance left feeling not invigorated by the promise of technological progress but “sadder,” “wiser” and, frankly, pretty creeped out.

Theater manager John Hollingshead provides one of the most detailed first-hand accounts of the presentation in his memoir My Lifetime (1895):

The Professor was not too clean, and his hair and beard sadly wanted the attention of a barber. I have no doubt that he slept in the same room as his figure—his scientific Frankenstein monster—and I felt the secret influence of an idea that the two were destined to live and die together. … One keyboard, touched by the Professor, produced words which, slowly and deliberately in a hoarse sepulchral voice came from the mouth of the figure, as if from the depths of a tomb.

Just one year prior to the Euphonia’s London debut, influential scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institute Joseph Henry had raved about its possible applications. Henry envisioned linking two Euphonias together via telegraph line so that one might read aloud a telegram sent by the other, essentially forming a convoluted telephone. (Imagine if, years later, instead of backing a young, nervous inventor named Alexander Graham Bell, Henry had pursued the Euphonia. Would every home in America be outfitted with a dead-eyed animatronic face that read electronic messages aloud in a ghostly whisper?)

Sideshow automaton’s voices were often faked by hiding a person somewhere beneath the apparatus. Viewers of the Euphonia were impressed because there was clearly no hidden chamber for such a ruse to take place. (Photo: Public Domain)

While in London, the Euphonia received some enthusiastic reviews. The Times even went so far as to proclaim it was “almost a duty of all who can afford to see it, to gratify at once their curiosity, and show their encouragement of genius.” So why did the general public so flatly reject Faber’s machine?

The answer may lie in a thought experiment put forth by the roboticist Mashahiro Mori in 1970. Mori proposed that “as [a] robot became more human-like there would first be an increase in its acceptability and then as it approached a nearly human state there would be a dramatic decrease in acceptance.” This dip in public approval represents a Goldilocks zone for robotic anthropomorphism: Robots who find themselves in it are simultaneously too human and not human enough. Faber’s Euphonia seemed to have gotten lost somewhere in what Mori called “the Uncanny Valley.”

A very realistic depiction of the Euphonia, from the 1870 London Journal. (Photo: Public Domain)

People liked that the Euphonia could parrot human speech. They enjoyed that it could change accents and languages with the turn of a screw or a stroke of a key. They didn’t like its vacant stare, its strange rubber tongue that lolled around its empty mouth as it spoke, or the fact that it seemed to “breathe” when Faber adjusted the bellows.

Sigmund Freud defined the uncanny as “that class of terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” The Euphonia, in spite of its familiar and quintessentially human ability to speak, was still undeniably inhuman; A mechanical imposter in a rubber mask.

Joseph Faber’s London exhibition was a crushing failure. He continued to tour the English provinces with the Euphonia, but according to Hollingshead, in these rural areas he was “even less appreciated.” More than a decade after London, in a lonely town deep in the English countryside, Faber destroyed the Euphonia before destroying himself. This final suicidal act crystalized him as the mad scientist archetype: a solitary figure, singularly obsessed with his work, whose monomania finally erupted into insanity.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) the creature tells his promethean creator that they are “bound by ties only dissoluble by the annihilation of one of us.” For Joseph Faber, freedom from his “child of infinite labor and unmeasurable sorrow” could come only from mutual destruction.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook