The American Textile Industry Was Woven From Espionage

A spinning frame at Slater Mill. (Photo: Bestbudbrian/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Samuel Slater, who established the United States’ first textile mill in 1793, is widely regarded as the father of America’s industrial revolution, having received that very accolade from Andrew Jackson. But American industry may owe as much to his fantastic memory and legally questionable sneakiness as his skill as a machinist and manager. This is the story of how the industrial pioneer earned his other title: “Slater the Traitor.”

The ninth of 13 children, Samuel Slater was born in Belper, England in 1768. At age 14, he entered a seven-year apprenticeship agreement with mill owner Jedediah Strutt. He proved a clever, talented young man and quickly became Strutt’s “right hand.” During Slater’s apprenticeship, he learned a great deal about cotton manufacturing and management. He had the opportunity to work on the machines, and saw how Richard Arkwright’s spinning frame—the first water-powered textile machine—was used in large mills. Unfortunately for the ambitious Slater, Strutt had several sons of his own. As a result, Slater would not have a path to advance in the business.

Mule spinning in action in a British mill, 1835. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In 1790, Slater decided to leave Strutt’s employment after coming across a Philadelphia newspaper that offered a “liberal bounty” (£100) to encourage English textile workers to come to the United States. At the time, England organized its economy to ensure that colonies (and former colonies like the United States) would continue to be in a position of “absolute dependence on Britain” as the major market for their cotton and other raw materials. Britain was happy to purchase American cotton but wanted to ensure that Americans could not process it themselves. In order to keep knowledge of cotton manufacturing at home, England passed laws in 1774 that prohibited both the export of technology and the travel or emigration of textile workers to the United States. The British, unsurprisingly, thought of the “inducements” to emigrate offered by the Philadelphia paper as little more than bribes.

Slater clearly understood the risks of going to America to start up cotton mills. When he boarded a ship bound for New York, he dressed as an English farmer’s son, not a machinist or mill worker. He took no machine plans or models with him. Instead, he “committed all the necessary information to his phenomenal memory.” He carefully concealed his indenture papers, which provided the only proof that he possessed some familiarity with cotton processing. Slater’s only concession to his family was a letter to his mother, which he sent just before the ship departed.

After spending a short time in New York City, Slater moved to Rhode Island, where he went into business with a few members of the Brown family (of Brown University fame) and William Almy. Once he arrived in Rhode Island, legend has it that it took him just one year to build the complicated Arkwright machines from memory. Soon they had plenty of thread to sell and Slater’s reputation was secure. In 1793, the newly established Almy, Brown, and Slater company built the mill that would usher in the American industrial revolution. The rest is history.

Samuel Slater. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Technically, Slater legally acquired the knowledge of the Arkwright’s water frame during his apprenticeship and therefore did not steal from his employer. It helps Slater’s case that Richard Arkwright himself was embroiled in a number of patent disputes. Challenges to the patent on the Arkwright frame resulted in the revocation of its patent a full five years before Slater left for America. It was Slater’s decision to leave England with protected industrial knowledge that was illegal.

Historians now think that Slater probably did not build the machines entirely from memory—Massachusetts textile workers had already attempted to replicate British textile machines and, apparently, Brown and Almy already owned a few inoperable machines that Slater may have reused or built upon. It took just two months to get Arkwright frames working and yarn spinning. This quick timetable suggests that Slater probably did not build all the machinery entirely from scratch.

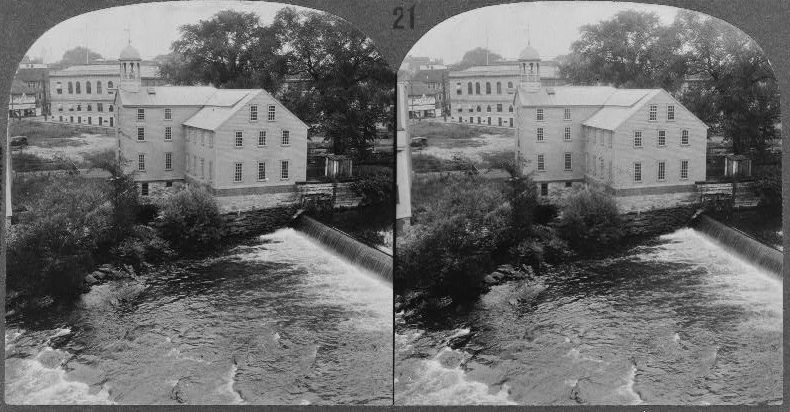

A stereograph from 1927 of Slater Mill, first cotton mill in United States. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The myth was useful, though. Americans like to believe in individualism and the United States as a land of opportunity. Slater’s story of sneaking out of England to make his fortune in the United States—and make a fortune he did, as when he died in 1835 he was worth over $10 million, or $250 million today—confirmed Americans’ ideas about themselves.

Today, we might see Slater as the quintessential entrepreneur. He managed to marshall local artisans, existing technology, capital from Brown and Almy, and grit to set up a wildly successful and wholly new enterprise. Thanks to Samuel Slater, the US processed over 40 times as much cotton in 1835 as it did in 1790. The British textile industry shrank as America’s industry expanded.

Although Slater’s contributions to American industry were widely celebrated during his lifetime, his native country was considerably less enthusiastic. Back home, textile workers called him “Slater the Traitor.” As late as 1905, British newspapers suggested that Slater “might have attained the highest eminence by continuing to live in England.”

There are signs, however, that Slater’s complicated legacy has improved since the early 19th century. In 1994, Belper and Pawtucket became sister cities. Twenty years later, his hometown of Belper unveiled a plaque at his childhood home. During the ceremony, Councilman Andrew Lewer said that, “although at the time he defied the law, I think today we can acknowledge [Slater’s] entrepreneurship and while we might not like what he did, I hope we can come together to recognise his importance.”

Slater Mill Historic Site in Rhode Island. (Photo: Doug Kerr/flickr)

In Rhode Island, Slater’s legacy is much less complex. Slater’s position as the father of American Manufactures includes links to slavery and child labor, but his contributions to the nation’s economic life are typically understood as a net positive contribution to the United States. Slater’s first mill is open to the public and part of Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor—the nation’s newest National Park.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook