The Belgrade Book Collection That Survived War, Fascism, and Neglect

One family has kept it going—and growing—since 1720.

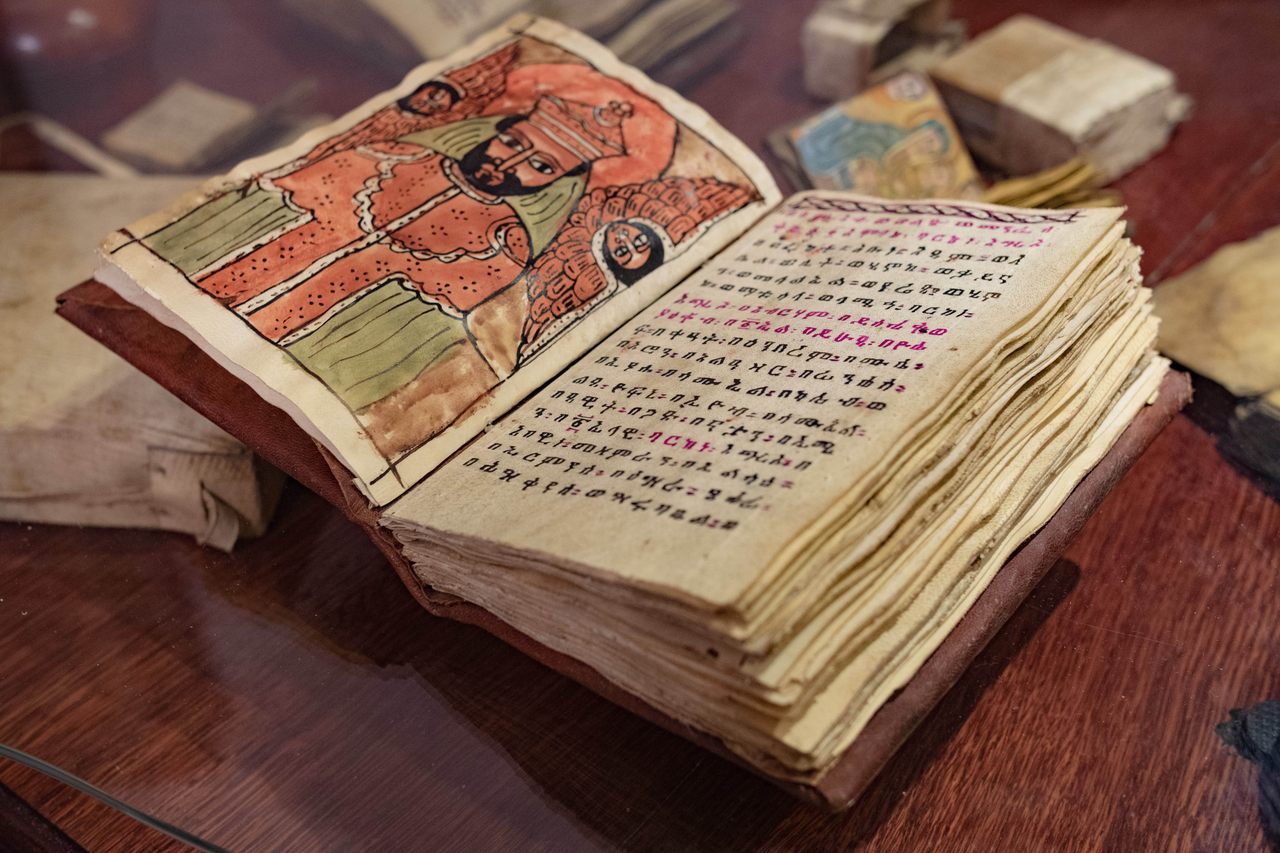

Viktor Lazic pauses in front of the first glass case on the ground floor of a small museum in Belgrade, Serbia. A parched manuscript lies below.

“This is made of rice,” he tells the group of visitors he’s showing around. “It’s a book from China, which you can eat if you are very hungry.” He gestures to the adjacent case, which contains a book from Thailand. “Then there is a book I don’t recommend you eat,” he says, with a smile and a flourish. “This is made from the dung of an elephant.”

The group titters.

Lazic is a 34-year-old writer, translator, and lawyer. He’s also a former president and trustee of the civil-society organization Adligat, which administers this vast and vibrant private collection of books that’s been in his family for nine generations. Founded by an ancestor in northern Serbia, the collection is divided into two parts: a book and travel museum, where the tour is taking place, and a museum of Serbian literature.

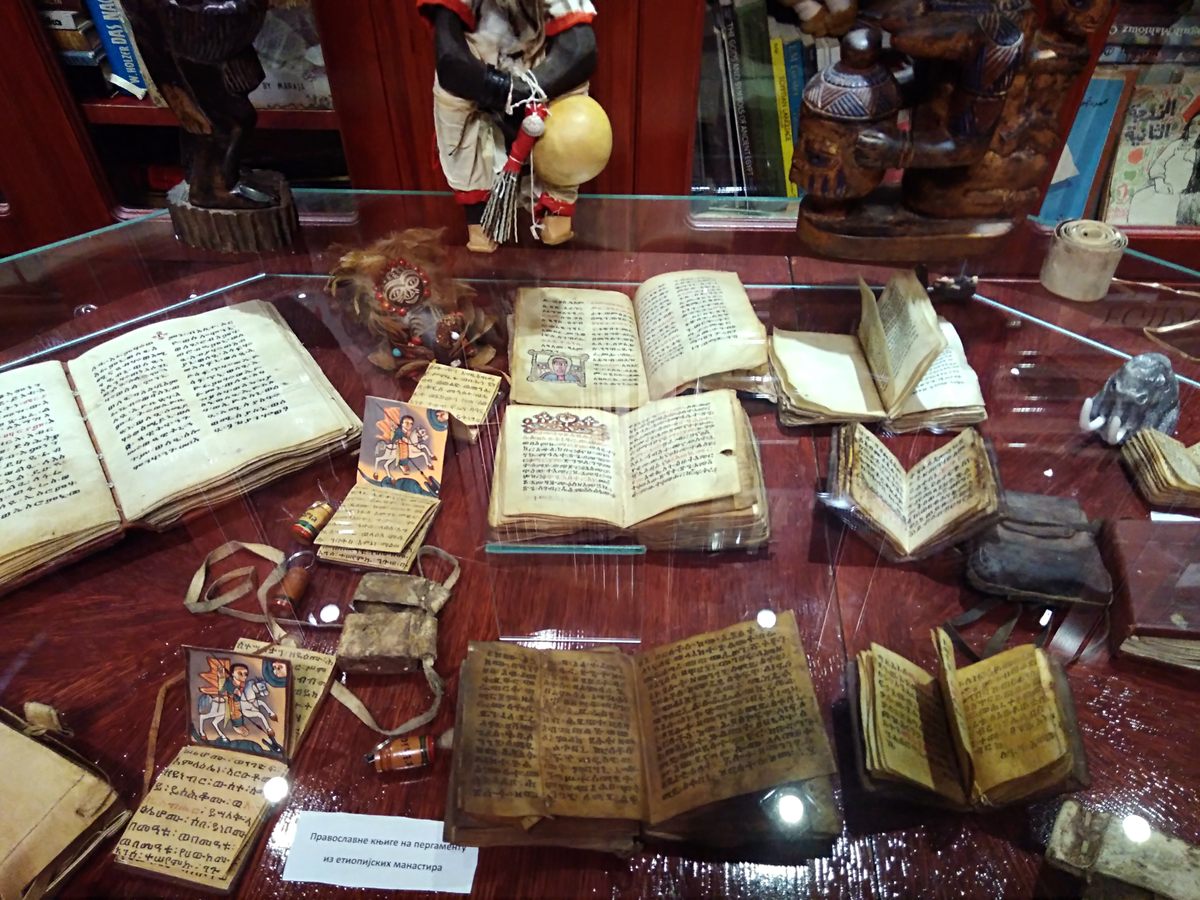

Lazic is leading the evening’s guests through a one-hour tour of the family home and library, where just a fraction of the million-plus books in the collection are currently displayed. The collection, spanning time and space, includes books from India, Algeria, Ethiopia, and Indonesia; books made from bamboo sticks, silk, and sheep foetuses; miniature books and scrolls; first editions and signed copies.

Lazic moves through the floors, unveiling trapdoors that lead to passageways and closets filled with books, books, and more books—a virtual tour of the world through the written word. Then he walks his guests through the Serbian rooms, which hold the letters of Nikola Tesla and the personal libraries and effects of Nobel nominee Miodrag Pavlovic and the novelist and poet Milovan Danojlić, among others.

When Lazic became aware of the collection as a young boy, in the 1990s, it had already survived since 1720, through multiple generations, wars, and dictatorships. Started by Mihailo Lazic—a forefather who was a priest, and therefore among the lucky few at the time to be educated—the library first opened to the public in 1882. It is a family enterprise that has grown with every generation, save for a brief stutter in the second half of the 20th century.

Before the tour began, the Lazic living room was buzzing with the strains of merriment, as writers and intellectuals sipped wine, snacked on hors d’oeuvres, and browsed through some of the works on display. They were here for the unveiling and donation of a new “legacy,” or personal collection, belonging to Tanja Kragujevic, a major Serbian poet, and her husband, Vasilije Vince Vujic.

Their works were gathered straightforwardly enough, but not everything in the collection has been. Indeed, Lazic later recounted dramatic instances of Adligat rescuing books from libraries about to shutter, and preserving valuable volumes slated for destruction.

“We are [like a] Red Cross for culture,” he says, after the tour. “We have a whole network—many institutions in Serbia and Europe—where when people [learn about] … books [that are going to] be destroyed, they call us.”

A recent example, he says, occurred some years ago, when a valuable collection at a Serbian library was about to be pulped. Concerned library officials called Lazic, and soon Adligat had 28,000 new books in its collection for safekeeping.

Other volumes in the Lazic library involved derring-do—and loss. According to one family story, Lazic’s great-grandfather Luka attempted to safeguard his own books from the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I by stitching them into his clothes. At the time, Luka lived in Vojvodina, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the war began, he fled to Serbia to avoid joining the army. He took several books with him in his thick sweater, believing they would be safer than at home.

Luka continued to carry them later, when he had joined the Serbian army, and—after Austro-Hungarian forces surrounded them on three sides—marched with troops (and civilians) through the snowy Albanian mountains. That episode, in 1915, was part of what came to be known as the Great Retreat—one of the most tragic episodes of the war.

Later, while traveling by boat from Greece to Corfu, Luka’s ship was torpedoed. The stash of books he had carried from home was lost when the boat capsized. Yet Luka continued to collect books during and after the war.

Many of the volumes collected from this period, deemed “important and fragile” by the British Library, were digitized in 2015–16 by the Belgrade University Library under a grant from the U.K. national library’s Endangered Archives Programme. The digitization covered 50,000 pages of damaged Serbian books, newspapers, war journals, calendars, and images.

“Serbian war publications are of great global importance because of the role and importance Serbia had in World War I,” says Vasilije Milnovic, an academic who received the grant and worked with the Belgrade University Library on the project.

The Lazic family collected and protected books through the next war as well.

As Lazic tells it, when the Germans invaded Serbia in 1941, his grandfather Milorad, Luka’s son, already had a thriving private library that rented books to people through an intricate network of bicycle routes. For the Germans this was ideal: They could deploy the network to distribute their own information and propaganda, and Milorad had little choice in the matter.

But since they didn’t trust him—perhaps because of his education, or his involvement in the previous war against the Germans—they enlisted his illiterate wife, Danica, instead. The first thing she did, Lazic says, was to contact communist groups fighting the Germans, and to offer to work for them as a spy.

During those years, the Lazic couple saved copies of all the written material they could, from both sides of the war, for their library.

Once the war ended and Josip Broz Tito came to power in Yugoslavia, the communists wanted the couple to turn over the material to the National Library of Serbia. But they were hesitant, both because of their personal attachment to the project and their concern that material perceived as anti-communist might be destroyed by the new regime.

“When the war ended,” says Lazic, “we had more than 50 editions of Mein Kampf. And my family didn’t want to destroy [them]. My grandfather said, ‘If you destroy Mein Kampf you won’t harm Hitler. [You will] harm our own history, because you [will be] destroying the physical traces of history.”

Milorad was determined to save the collection for posterity. So the Lazic family gave several books to relatives and friends for safekeeping, and, in 1946, buried 2,000-3,000 volumes in the ground beneath Vojvodina, eventually retrieving the books decades later, in the 1970s.

“Luka, my great-grandfather, had one rule,” says Lazic. “He wrote it down: [It was to] … preserve every kind of book, regardless of context.”

For a while, the Lazic family library was inactive. Milorad died in 1977, and the collection languished for a time. Lazic’s father’s generation, including his father’s siblings, lost interest in maintaining it, and the next generation was still too young to help out.

In the 1990s, when Yugoslavia cleaved into different states amid the fall of communism, books about communism became threatened under the new regime. By this point Lazic had been inducted into the family business of saving books by his aging grandmother Danica.

“We saved those books the same way we saved fascist books,” he says. “Not because I love communism, but because it’s part of the history of this nation.” The Lazic collection today includes more than 30,000 books about communism.

Lazic’s uncle Milorad Vlahovic, a nephew of Danica’s, had also heard the stories of his aunt’s work as a spy during the war, when she adroitly used the bicycle routes for sharing information with partisan resistance groups. Vlahovic, 61, was familiar with family lore as a child, breathing in the library’s ancient scents and marveling at the endless stacks of books. That the legacy continues is, for him, a matter of joy.

“This is in Viktor’s blood,” says Vlahovic, as his daughter Milica translates from Serbian. “He was always obsessed with the collection. We are happy and proud that he has done this for the library, for the family, for the country.”

Adam Sofronijevic, the deputy director of the Belgrade University Library, had also heard several of these accounts from Lazic and his parents. “Some of these stories are fascinating and tell us a lot about Serbian society and culture,” he says. “[Taken as a whole, it] is a story of book-loving, book-keeping, and enthusiasm beyond and above the usual.”

Now overseen by a trust, Adligat—formally registered as a nonprofit in 2013—has a skeletal staff of five unpaid volunteers. Financially it’s sustained through multiple means: by charging scholars for access, as a ticketed museum with organized tours, through donations, and by family and state funding.

Each workday, about a thousand more “units”—books, magazines, and manuscripts—are donated by various institutions, private collectors, and individuals. “To give books is good karma,” says Filip Tomasevic, a local collector who donated about a thousand euros’ worth of books on the evening of the tour.

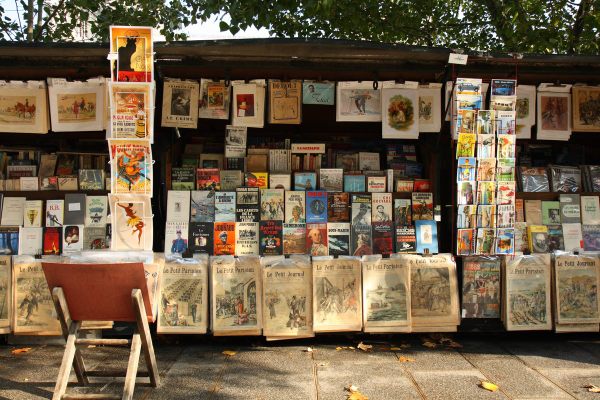

A prime resource for researchers, Adligat also lends parts of its collection to museums across Europe. Lazic, who remains on the hunt for more books, travels around the world—sometimes buying, sometimes receiving donations, sometimes accepting books and passing them on to other libraries. The day of the tour, Lazic said his car contained books from various donors worth more than 30,000 euros.

“I wanted to build a safe haven—a place where people of culture can entrust what’s valuable to them,” he says. “My family gathered something that is important for the nation. We hope to preserve it for the future.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook