The Early Spy Manual That Turned Bad Middle Management Into An Espionage Tactic

The Simple Sabotage Field Manual, declassified in the 1970s. (Photo: Joe Loong/Flickr)

When you think of Allied espionage, you might imagine disguised explosives, wiretaps, bat bombs, or other dramatic inventions. But declassified documents reveal that World War II was won in part by more everyday saboteurs–purposefully clumsy factory workers, annoying train conductors, and bad middle managers, all trained by the U.S.’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual.

In 1944, World War II was in its final throes. Though the Allies were holding their own against the Axis, they were in need of more troops and more local cooperation. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a precursor to the CIA, envisioned a special kind of special forces–an army of dissatisfied European citizens, waging war on existing governments simply by doing their jobs badly. They wrote up the Simple Sabotage Field Manual, a kind of ultimate un-training manual, which was full of ideas for motivating and inspiring locals to make things harder on their governments. Selections and adaptations from it were disseminated in leaflets, over the radio, and in person, when agents met people who seemed right for the job.

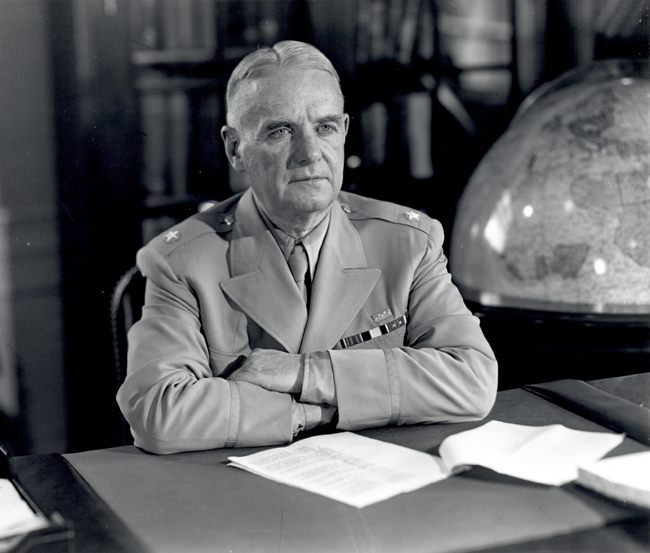

William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, first head of the OSS and supervisor of the Simple Sabotage Manual. (Photo: National Archives & Records Administration/Public Domain)

There are “innumerable simple acts which the ordinary individual citizen-saboteur can perform,” the manual’s introduction promises. It is possible to commit destruction with “salt, nails, candles, pebbles, thread, or any other materials he might normally be expected to possess.”

The potential of these materials is limited only by the saboteur’s imagination and circumstances. You could jam a lock with a hairpin, drop a wrench into a fusebox, or sand a surface that’s supposed to be lubricated. As the manual explains, thinking bigger is better. Any military factory worker could easily slash an army truck’s tires on their way to work–but it’s even better to spill a bunch of hair into an assembly-line cauldron, spoiling the rubber meant to outfit a whole fleet.

A second type of simple sabotage, the manual explains, requires no tools and produces no physical damage. Instead, “it is based on universal opportunities to make faulty decisions, to adopt a non-cooperative attitude, and to induce others to follow suit.” Like all good maneuvers, this tactic gets a fancy name–”the human element.” Once again, there’s a simple sabotage for every occasion. Citizens should “cry and sob hysterically at every occasion, especially when confronted by government clerks.” Train conductors can “issue two tickets for the same seat in the train, so that an interesting argument will result.” Most impressively, any audience member can ruin a propaganda film by bringing a bag of moths into the theater: “Take the bag to the movies with you” and leave it on the floor of an empty section of the theater. “The moths will fly out and climb into the projector beam, so that the film will be obscured by fluttering shadows.”

Middle managers, especially, can get in on the act. Those with white-collar jobs should pontificate, flip-flop, and take every decision into committee, says a section on ‘General Interference with Organizations and Production.’ “Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible,” the OSS advises. Promote bad workers and complain about good ones. “Haggle over precise wordings… Hold conferences when there is more critical work to be done.”

CIA’s manual for “simple sabotage” from 1944. Sounds like the management training manual for some jobs I’ve had. pic.twitter.com/TN7MdiPF8m

— Lars Doucet ن (@larsiusprime) November 3, 2015

To a reader entrenched in modern-day bureaucracies, this sounds a little like how things go even when no trickery is planned. “Some of the instructions… remain surprisingly relevant” as “a reminder of how easily productivity and order can be undermined,” writes the CIA website. A few businessmen recently wrote an advice book based on the Simple Sabotage manual, meant to help frustrated higher-ups “detect and reduce the impact” of saboteur tactics.

This is a thoroughly contemporary take, though. At the time, the OSS was careful to point out to saboteur recruiters that most people are not naturally prone to idiotic decisions. “Purposeful stupidity is contrary to human nature,” they write in a section called “Motivating the Saboteur.” Your average recruit “frequently needs… information and suggestions,” incentives, and the assurance that there are many saboteurs like him, sanding things that don’t need to be sanded, holding meetings that don’t need to be held, and bringing bags of moths to the movies.

The whole manual is available for your perusal. Pages 8 through 11 have good instructions for setting almost anything on fire. Page 19 teaches you how to derail mine cars. And remember, if you are caught, “always be profuse in your apologies.” Happy trails, saboteurs.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook