The Illicit Spelunker Capturing Underground Scenes at Chernobyl

Photos from the most hazardous part of the infamous Reactor No. 4.

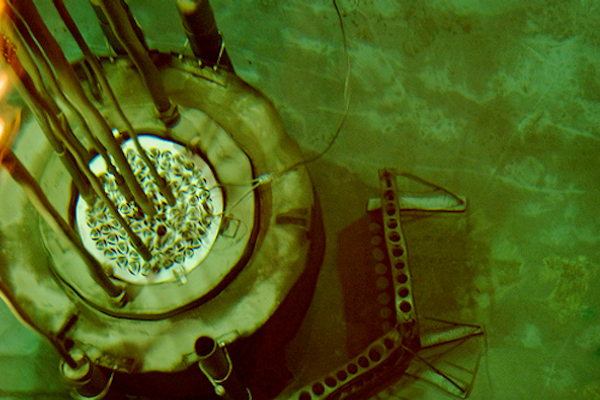

Wrecked machinery in the Chernobyl sarcophagus. (All Photos: Alexander Kupny)

It is hard to imagine the circumstances why someone would want to climb into a small hole under the Chernobyl’s infamous—and dangerous—charred No. 4 reactor.

But Alexander Kupny did just that, many times.

The explosion that occurred on April 26, 1986, blew off the building’s four million pound concrete roof, as well as the upper walls, and part of the machine room. The fire burned at over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The tremendous heat melted iron, steel, cement, machinery, graphite, uranium, and plutonium, turning it all into a running lava that poured down through the blown floors of the reactor complex. The lava eventually cooled into stalactites, black, sparkling, and impenetrable, emitting 10,000 roentgens of radioactivity an hour. To translate that measurement, five minutes of exposure to 10,000 roentgens would kill most people.

Rear view of sarcophagus.

In 1989, Kupny worked as a health physics technician at Reactor No. 3, which was paired with Reactor No. 4 and still functioned after the accident. A radiation monitor by trade, he had volunteered to go to Chernobyl in the late 1980s because he believed it was his patriotic duty to help out after the catastrophe. He was also intrigued professionally. The smoking Chernobyl plant had radiation levels like nowhere else on earth. Chernobyl, Kupny said, was “the Klondike of radiation fields.”

He had a chance to measure radiation at levels few others could experience. “I didn’t look at the Chernobyl sarcophagus with fear,” he said over coffee in his hometown of Slavutych, Ukraine. “I saw it as a phenomenon. You can’t study something you fear.”

“The elephants foot,” extremely radioactive, hardened lava from reactor fuel and metal.

As the years went by, Kupny grew more curious. He had measured radiation levels at nuclear power plants his entire career. He was an expert at visualizing the invisible—as a monitor, not a scientist, a blue collar job at reactors. He wanted to experience firsthand the tremendous power of splitting a nucleus. Per his job classification, Kupny had a pass to the hottest areas on the terrain, including the sarcophagus, the vast concrete tomb built around the smoldering reactor in the months following the accident. The sarcophagus had two cave-like openings used by workers after the radiation levels had cooled to access the crushed control and machinery rooms.

From 2007 to 2009, the unauthorized underground trips became reality. Kupny had the necessary equipment—hazmat suits, gas masks, and radiation detectors. He also possessed a camera. His friend, Sergei Koshelev, had a video camera. Kupny and Koshelev had no formal permission to take their cameras and headlights on their days off and crawl into the sarcophagus, but they knew the guards and the workers, and no one stopped them. “We went there as partisans,” Kupny explains, “We took on the risk ourselves. The fewer people who knew about it, the better.”

Central hall of the ruined reactor.

The risks were considerable, though Kupny is cavalier about them. The caverns under the reactor are former rooms—the control room, the turbine halls—but they are no longer in the same places as when the reactor was operating. The basement of the turbine generator hall is filled with water. Oil, slimy and slippery, seeps everywhere. The men must step lightly around cables, potholes and ankle-trapping crevices. “Just walking,” Koshelev notes, is “a hazard.” It is easy to stumble over rubble and cables, to pitch into a hole, break a leg or arm. Heavy doors can swing shut and jam. Flashlight batteries are not reliable when exposed to ionizing radiation and they give out, not gradually, but suddenly with no warning. In a pitch of total blackout, they would then have to feel their way out of the crypt, trying not to panic over the extra time spent exposed. They had a half hour, 40 minutes max, to stoop, crawl and wriggle into the underground chambers, take pictures and get back above ground before they were overexposed.

The photos Kupny snapped look like an episode from the Planet of the Apes. Wrecked machinery and dated equipment lie upended amidst peeling paint, and rusting, twisted steel. Clouded, frozen control room dials rest amid wires dangling from fuses. Scattered everywhere are cement blocks tossed on end. Yet the most haunting aspect of Kupny’s already-haunting photos is the snowfall of tiny crystalline flakes that float through every scene of silent ruin lending the photos a deep-sea feel.

Remnants of uranium fuel rods.

The tiny orange flecks are not an aberration in Kupny’s film. As Kupny snapped photos, the multitude of photons of radioactive energy swarming around him imposed their image on his film. Imperceptibly, as Kupny pressed his shutter button, the effervescence of the decaying reactor fuel jeweled the atmosphere in the buried chamber, lighting it up like an elaborate, spidery chandelier. These points of light are not representations. They are energy embodied. The specks are none other than cesium, plutonium and uranium self-portraits.

I asked Kupny why he went down there. Was it the same motivation that drives people to climb Mt. Everest—namely, that it exists? Kupny bristled at the comparision “I don’t do it to put a flag down and beat my chest,” he replies, “I went under to figure out what happened. I see nuclear energy as a natural force. I want to understand this force; the immense power behind the accident. Unless you go there, you can’t understand it.”

Deconstruction of power plant buildings.

Kupny is now retired from nuclear work, and in his mid-60s he looks spry and healthy. He knows he took risks entering the sarcophagus, a place where only workers go when a job can’t avoid being done. “For some people,” he smiles optimistically, “radiation works on them like it does on food—as a preservative.”

Research for this article was funded in part by the American Council of Learned Societies. This essay was adapted from the forthcoming book, Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, to be published by Island Press in 2017.

*Update, 4/12: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Slavutych as being in Russia, not Ukraine. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook