The Morbid Journey of Cromwell’s Traveling Head

In January of 1661, King Charles II of England ordered the exhumation of the corpses of Henry Ireton, John Bradshaw, and Oliver Cromwell. He arranged to have the bodies hanged and beheaded because the three men presided over the trial and execution of his father, King Charles I.

The corpses were hanged at the Tyburn gallows, and their bodies were left there until the afternoon. The corpses were then decapitated and buried under the gallows. According to tradition, it took eight blows to separate Cromwell’s head from his corpse.

The heads of Cromwell, Ireton, and Bradshaw were impaled on 20-foot spikes through the base of the skull then displayed on the roof of Westminster Hall. Cromwell’s head stayed on the spike for more than 20 years before it disappeared.

Drawing of Cromwell’s head, from Pennant’s ‘London’ (1790) (via Wikimedia)

Drawing of Cromwell’s head, from Pennant’s ‘London’ (1790) (via Wikimedia)

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) is considered an enigmatic and contentious historical figure. He became a Puritan, committed to carrying out God’s plan following a spiritual crisis in the 1630s. He started out as a Member of Parliament during the reign of King Charles I (1600-1649), but became Lord Protector after the execution of the king.

The English Civil War (1642-1651) started when King Charles I and members of Parliament couldn’t agree on reforms that would check the King’s power. Cromwell fought on the side of the Parliamentarians against the Royalists and commanded successful military engagements that led to their surrender.

Cromwell played a decisive role during the trial of King Charles I, and was one of the people who signed his death warrant. In 1653, he was sworn in as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland for life. Cromwell died in 1658 at the age of 59 from an infection of his urinary tract or kidneys. During a post-mortem examination, Cromwell’s cranium was cut open so his physician could study his brain, then his body was embalmed and buried in Westminster Abbey.

Charles II returned to England after Cromwell’s death and made sure all of the signatories to King Charles I’s death warrant were punished.

Oliver Cromwell’s death mask at Warwick Castle (photograph by Terry Robinson/Flickr)

Oliver Cromwell’s death mask at Warwick Castle (photograph by Terry Robinson/Flickr)

While the whereabouts of the heads of Ireton and Bradshaw have drawn little interest, the Lord Protector’s remains have attracted considerably more attention.

In 1875, Dr. George Rolleston examined two heads that were reported to belong to Cromwell, and compared them to Cromwell’s death mask. The first was a skull from the collection at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. Rolleston believed this skull didn’t belong to Cromwell because the damage around the hole in the parietal bone indicated that a spike entered from the top of the head, not the bottom. Also, there was no flesh left on the skull and no evidence that it had been embalmed.

Rolleston then compared a second head, known as the “Wilkinson head,” (pictured here and here) to Cromwell’s death mask. He considered this to be the best candidate for Oliver Cromwell’s head.

According to Wilkinson family legend, Cromwell’s head came into their possession thanks to a powerful gust of wind that blew it off the roof of Westminster Hall during a violent storm in 1688. A guard found the head and took it home where he hid it in his chimney and kept it a secret. As the guard lay dying he told his family about the head, and soon after his death his daughter sold it. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it passed through the hands of museum owners and collectors who displayed the mummified head for money.

In 1815, the head was sold to Josiah Henry Wilkinson, and stayed in the Wilkinson Family until it was buried in 1960. The Wilkinson family allowed scientists to study the head, including Dr. George Rolleston in 1875 and Karl Pearson and Geoffrey Morant in 1935. Pearson and Morant examined the head for their book, The Portraiture of Oliver Cromwell With Special Reference to the Wilkinson Head. They determined the head belonged to a man who was about 60 years old when he died, and argued that the cranial measurements corresponded to portraits of Cromwell. The skullcap showed evidence of having been removed and then reattached with embalmed skin, which corresponded to historical reports. Pearson and Morant concluded that this was likely the mummified head of Oliver Cromwell.

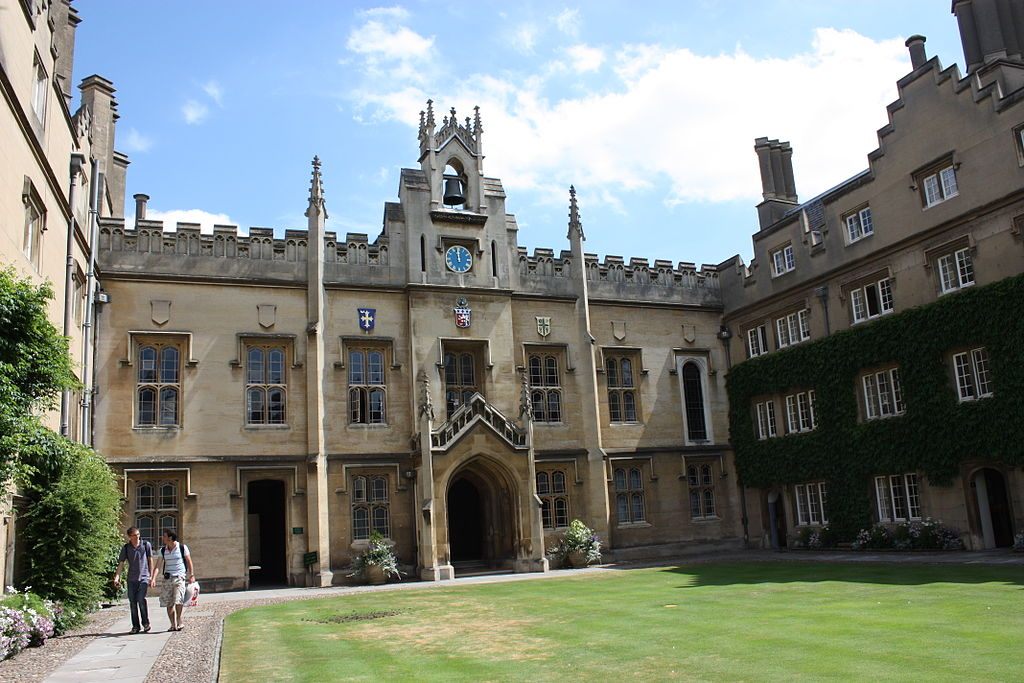

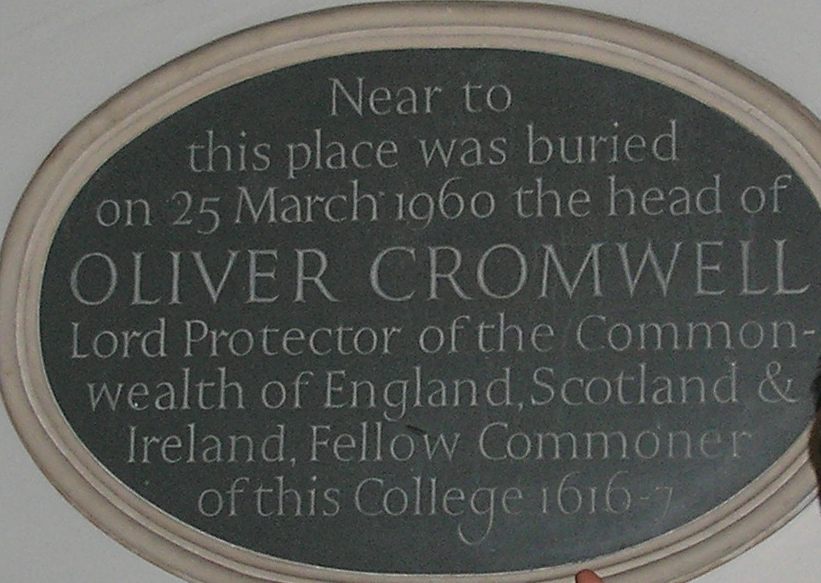

The Wilkinson Family decided to give the mummified head a proper burial in 1960. They contacted Cromwell’s college, Sidney Sussex, and interred the head in an unmarked grave.

Sidney Sussex College, where Cromwell’s supposed head is now buried (photograph by Ardfern/Wikimedia)

Sidney Sussex College, where Cromwell’s supposed head is now buried (photograph by Ardfern/Wikimedia)

Plaque for Cromwell’s head at Sidney Sussex College (photograph by Doctorpete/Wikimedia)

Plaque for Cromwell’s head at Sidney Sussex College (photograph by Doctorpete/Wikimedia)

For more fascinating stories of forensic anthropology visit Dolly Stolze’s Strange Remains, where a version of this article also appeared.

Morbid Mondays highlight macabre stories from around the world and through time, indulging in our morbid curiosity for stories from history’s darkest corners. Read more Morbid Mondays>

References:

Howorth, H.H. (1911). The head of Oliver Cromwell. The Archaeological Journal, volume 68. Retrieved from: http://books.google.com/books?id=4aE8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA241&lpg=PA241&dq=george+rolleston+cromwell+skull+ashmolean&source=bl&ots=k5Ue5JWrpQ&sig=UwKP7GSHf0-4uDqkVrksmjtVZio&hl=en&sa=X&ei=QTlpVMCAPK33igK58ICYDA&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=george%20rolleston%20cromwell%20skull%20ashmolean&f=false

Kennedy, M. (2009). Oliver Cromwell’s grave comes back to life for summer at Westminster Abbey. Retrieved from: http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/aug/02/cromwell-grave-westminster-abbey

Lovejoy, B. (2013). Rest in Pieces: The curious fates of famous corpses. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Smyth, D. (1996, August 11). Is that really Oliver Cromwell’s head? Well … LA Times. Retrieved from: http://articles.latimes.com/1996-08-11/news/mn-33204_1_oliver-cromwell

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook