The Mysterious Origins of a Food That’s Always Been Funny: The Sausage

Across civilizations and cultures, encased meat has been a human staple.

Grilling sausages. (Photo: oatsy40/CC BY 2.0)

This July, a sausage party is coming to Taipei. An actual sausage party, a sausage bacchanal at the Taiwan Design Centre, featuring a smoky-scented sausage mist that descends upon visitors, a sausage-festooned chandelier, sausage carnival games, and, of course, sausages to eat—a hypnotic twist of yellow and red sausages, a sausage in a banana peel, and sweet rice pudding sausages.

Taipei was named World Design Capital this year, and the event is one of a series of design-oriented programs to mark it; Bompas & Parr, the London-based experience design group, is partnering with Taiwanese designer Alice Wang to put together the sausage fest as part of the Food Project, which explores street and snack food as a design experience. Bompas & Parr had hoped to highlight a culinary overlap between British and Taiwanese culture. What they found is that sausages are much bigger than that.

“We obviously tapped into something that shows similarities and differences in every country on the planet, that’s the point of it—it’s a small word with sausages,” says Sam Bompas, co-founder of the group. “Everyone is different, but there is this commonality: We all love sausages.”

The “sausage instrument” from Bompas & Parr for the Taipei sausage festival. (Photo: Courtesy Bompas & Parr)

And we do. Forget love, forget war, forget decency and kindness or cruelty and apathy—it’s sausages that all of us, all over the world, have in common. Virtually every culture, tribe, nation, ethnic group has a sausage; most of them have many. In Taiwan, where Bompas & Parr are unleashing a sausage onslaught, roving sausage sellers offer patrons the chance to double their sweet, garlicky sausage take by betting on dice in called “sausage gambling” or xi ba la; in China, there’s lap cheong, a smoked pork sausage sometimes flavored with rose water or rice wine, or yun chang, a duck liver sausage; in Kazakhstan and other Central Asian nations, people eat a traditional horse meat sausage called kazy; the Greeks have long enjoyed loukanika, a pork sausage mixed with orange peel and fennel; Britons love sausages, from breakfast chipolatas to the classic Cumberland to black pudding, a blood sausage, possibly a hold over from Roman occupation; and Americans revere the hot dog, a German import, right up there with apple pie.

The ubiquity of the food makes it hard to trace its first moments on Earth; sausages were a solution to a problem that every culture was likely to come up against. “Sausages were created originally for two reasons: One, to make use of every little piece of the meat, so nothing is wasted, and two, by using salt and smoking, it was a way to preserve it,” explains Gary Allen, author of Sausages: A Global History, pointing to the rise of coordinated hunting and the ability to pull down increasingly larger game as one of the conditions that led to the birth of sausages.

Lap cheong, a type of pork sausage from China. (Photo: Mo Riza/CC BY 2.0)

The word we use now, “sausage”, comes from the Latin word salsus, meaning “salted” and the Old Northern French saussiche, but sausage’s roots go much deeper. The historical record on sausages begins around 4,000 years ago. Texts from the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia mentioned meat stuffed into intestinal casings, as well as other delicacies such as pickled grasshopper. Sausages make infrequent but important appearances in the historical documentation thereafter, showing how entrenched sausages were in their culinary cultures: In 1500 BCE, ancient Babylonians were using fermentation to make sausages; Egyptian murals depicted blood sausages being made from sacrificial cattle; in the 9th century BCE, Homer’s peripatetic Odysseus is described as a “rolling from side to side as a cook turns a sausage”, stifling his rage at the encampment of suitors who have laid siege to his home; and a Chinese goat and lamb sausage was recorded as early as 589 BCE.

But what exactly makes something a sausage? “It’s a complicated issue, where to draw the line,” agrees Allen. Sausages are a forcemeat—they are usually, but not always, chopped or ground meat, usually, but not always, forced inside a casing. The meat can be nearly any animal protein, from kangaroo to shellfish, although it’s usually pork, owing to the peculiar coagulating quality of pork juice and fat, and to a lesser degree, lamb or beef; some sausages also use animal blood, in combination with grains, cornmeal or oats, to bind it together. Proteins in the meat bond together in the cooking, drying or fermenting process, meaning that the sausage’s inside doesn’t crumble when sliced. Smoked sausages work on the principal that smoking creates an outer, preservative layer on the meat that will help make it resistant to bacterial spoilage, but other preservatives such as lactic acid fermentation and salt are also used.

Making kazy, a type of sausage made from horsemeat and eaten in Kazakhstan and other Central Asian nations. (Photo: donikz/shutterstock.com)

What kinds of sausages flourished where had everything to do with climate and culture: For example, countries in the Middle East were less likely to develop pork sausages, owing to religious prohibitions, while countries with a warmer climate were more likely to dry-cure their sausages.

“If you look from north to south in Europe, you’re going to find a lot more dried sausages in the southern area, the south of France, Greece, Italy, because it’s easier to dry the meat there,” explains Allen. “As you go farther north, you tend to have more fresh or smoked sausages, because it’s cold and damp. You’re going to find a lot of salamis in Italy, you’re not going to find a lot British salamis.”

Class comes into play as well, although perhaps not as much as you might think. “They were originally very sort of low class because fresh meat was more expensive, richer people would roast large pieces of meat and fresh where poor people would have it preserved and whatever is left over,” says Allen. That said, there is ample evidence that sausage was eaten across the socio-economic spectrum in various places, in various times. Historian Kate Colquhoun, in her book Taste: The Story of Britain Through Its Cooking, explained that because most people hunted during the Anglo-Saxon era, particular cuts, preparations, or kinds of meats were not class-specific; eating sausage through the winter was necessary for the survival of everyone, lord and cottager alike. Scholar and theologian Alexander Neckham, living in the 12th century in England, noted three different types of sausages prepared in the kitchens of wealthy people in his De utensibilus. In Tudor England, pigges rolles, an ancestor to the modern sausage roll, would have taken considerable time and effort to produce, indicating a high-status foodstuff. Queen Victoria was reportedly partial to a sausage herself, provided the meat was chopped not minced.

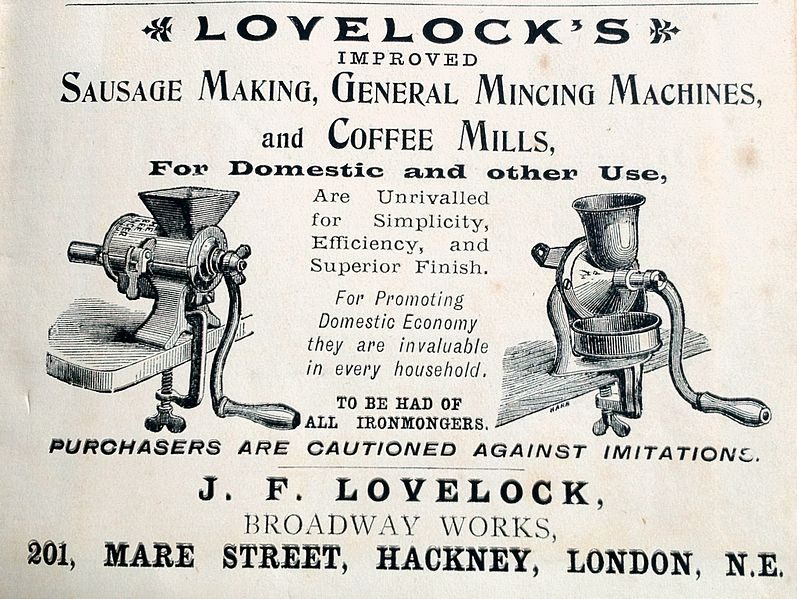

An 1894 advertisement for a sausage making machine. (Photo: Schnäggli/CC BY-SA 3.0)

And when the middle classes arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries, they too ate sausages, cooked slow, according to a popular cookbook of the day, to prevent their skins from popping. People love sausages because, of course, they taste good, and that transcends class. “It’s the combination of fat salt and texture and sometimes a bit of sugar in there as well, that makes it high in hedonic value but makes it comforting as well,” says Bompas.

Sausages have also nearly always been funny. The fact that sausages resemble penises has been lost on precisely no one throughout the ages, from Ancient Greek playwrights to modern filmmakers (see Seth Rogen’s forthcoming Sausage Party). It allegedly provided not only the justification for their inclusion in the ancient fertility festival Lupercalia, but also part of the reason that Christian Emperor Constantine I later banned them. (This, notably, was not the only time that Christianity and sausages collided: In 1522, Reform Protestantism was born when a group of proto-Protestants got together to eat sausage during Lent.) “It lends itself to a humor that is truly international—that’s why a sausage is funny in every language,” says Bompas.

Grilling sausages in Bonn, Germany, 1968. (Photo: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F027081-0011a / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

But for all the joy they bring, sausages remain somewhat suspicious. What made sausages useful and popular—the fact that off-cuts and offal could be made edible—also lent them a mystery meat stigma; that sausages were sometimes at the center of food poisoning outbreaks also didn’t help. In the 10th century, for example, Byzantine Emperor Leo VI outlawed blood sausages for a time after an outbreak of food poisoning associated with their consumption. In 1820, German doctor Justinus Kerner was one of the first people to consider the therapeutic uses of botulinum toxin, strain of bacteria typically found in pork (and used in Botox); he dubbed the effects of the toxin in humans wurstgift or “sausage poisoning”, so closely linked were food poisoning and sausages.

The 19th century saw a rise in fatal food poisoning cases in Europe and Britain, a by-product of the Industrial Revolution, urban crowding, and poor food hygiene in poverty-stricken rural agricultural areas. By the middle of the 19th century, sausages in Victorian England had become emblematic of the public health crisis that diseased meat represented, especially after several high profile outbreaks of food poisoning were blamed on bad sausages. In America, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, published in 1906, revealed that sausages were stuffed with rat feces, rats themselves and the poisoned bread used to kill them, spoiled sausages that had been returned unsold to the plant, and myriad other horrors; when smoking the sausages took too long, they were treated with borax and gelatin to turn them brown. Against later claims that his book too sensational to be true, Sinclair declared it as accurate “as a work of reference” and, happily, it led to the formation of food safety commissions in America. Sausage’s reputation (mostly) recovered.

Sausages on display in Lisbon. (Photo: Marijke Blazer/CC BY 2.0)

Mostly. In July 2015, British newspapers reported that Britons, a very sausage-happy nation, were eating 2 billion fewer sausages than they had in 2008. The Guardian attributed the decline in sausage sales to the fact that shoppers preferred chicken or steak to the “cylindrical tube of intestine stuffed with naught but pure evil” and “bulked out with chemicals and wheat rusk”. Just a few months later, concern over what mysteries sausages might contain was compounded by the reported link between cured, smoked and processed meats and cancer. In October 2015, the World Health Organization declared that bacon, ham, sausages, and other processed meats were as carcinogenic as cigarettes. Despite people turning to social media in droves to proclaim that they wouldn’t want to live in a world without bacon anyway, sales of sausages and other processed meats plummeted in the UK in the weeks after the WHO’s announcement. (Hot dog sales in America, however, appear to remain steady, according to the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council.)

But will the humble sausage ever leave our global plates? The Daily Mail thinks so, declaring that if trends continue, British sausages will go the way of “offal and faggots”. But in reality, probably not. “Sausage is such a blank canvas, it’s easy to innovate with sausages,” says Bompas, “I can still see the sausage being a firm and snappy contender for years to come,”.

Plus, we kind of like a little danger in our dinner. “I feel like if I give up things like sausages and bacon and I live for five years longer, ” says Allen, “but that meant that was five years of no sausages and no bacon, I cheated myself.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook