The Rise of the Gay Mafia, a Powerful Cabal That Never Existed

Before the gay agenda there was the homintern.

The paranoia over an “international homosexual conspiracy” rivaled the McCarthy communist witch hunts of the 1950s. (Photo: US Senate/Public Domain)

The idea of a “gay mafia” may seem like a bad oxymoron.

But there was a time in American history when there was a real fear that a gay mafia—known collectively as “hominterns”—existed, wielding control across Hollywood and throughout the arts and entertainment industries.

In his new book Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World, English academic Gregory Woods chronicles the rise of the “homintern,” exploring how the longstanding fear of homosexual men spurred a century-long paranoia about an alleged gay mafia controlling areas of government, the arts and academia.

The cover of Gregory Woods’ Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World. (Photo: Courtesy Yale University Press)

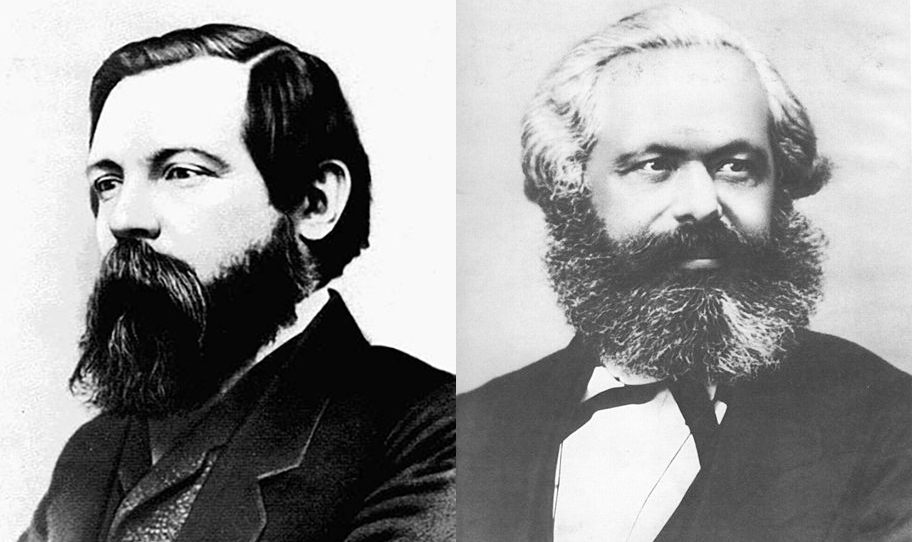

Woods traces the origins of this paranoia first to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, two well-known social theorists who espoused the idea of a communist society. In the mid-19th century the pair corresponded about the threat of “pederasts”—an antiquated term referring to men who had sex with younger men, since “homosexual” did not yet exist as a label—to their goal of establishing non-sexual comradeship between other men. As their aim was to establish a united front between men committed to dismantling class hierarchies, Marx and Engels feared that “pederasts” would threaten this bond, confusing fraternizing if a sexual desire was thrown into the mix.

Friedrich Engels (left) and Karl Marx. (Photos: Public Domain)

Yet the concerns of Marx and Engels were somewhat indicative of the times. The mid- to late-nineteenth-century saw a growing interest in studying male same-sex attraction, harnessing an understanding of it through pathologization and categorization. Woods writes that it was this obsession to categorize so-called “unsaid” male sexual impulses and behaviors that actually encouraged the fear of the homosexual figure in larger society. Since there was no term to refer to this same-sex attraction, the “pederast” proved an ominous and threatening figure because there was no medical understanding to the identity.

There is some irony to this history, as the term homosexual was first coined in 1868 before the word “heterosexual” even existed. Homosexual was set in opposition to the idea of a “normalsexual,” a word which was later discarded for “heterosexual.” This desire to study and define sexual behavior further pushed researchers to “un-closet” the homosexual, all in an effort to demystify a sexual identity that had long been ostracized and stigmatized but never really pinned down through scientific inquiry.

Soon enough, the idea of the “homintern” came along.

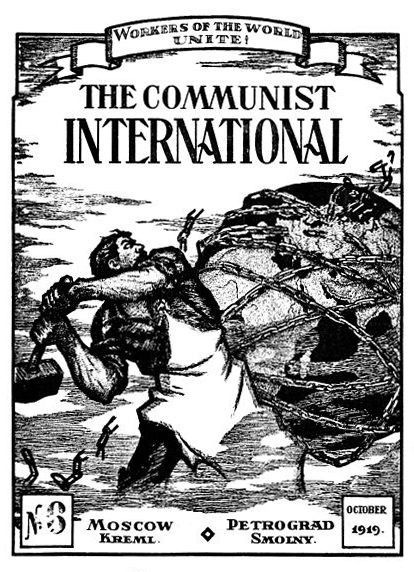

The term was allegedly first coined as a joke, taking its inspiration from the communist term “Cominterm,” an abbreviation of the Communist International Organization founded in the 1910s. Woods says it was most likely invented as a word play, referring to a disorganized and informal network of gay men who fraternized in the 1930s, including the likes of poet W. H. Auden and critic Cyril Connolly.

The English language version of The Communist International. (Photo: Public Domain)

Decades later,“homintern” entered Cold War discourse, being reappropriated by conspiracy theorists that exploited its communist association and claimed it referred to a longstanding “international homosexual conspiracy” across the country, whose one goal was to penetrate positions in the American government and usurp traditional American values of family and heterosexuality.

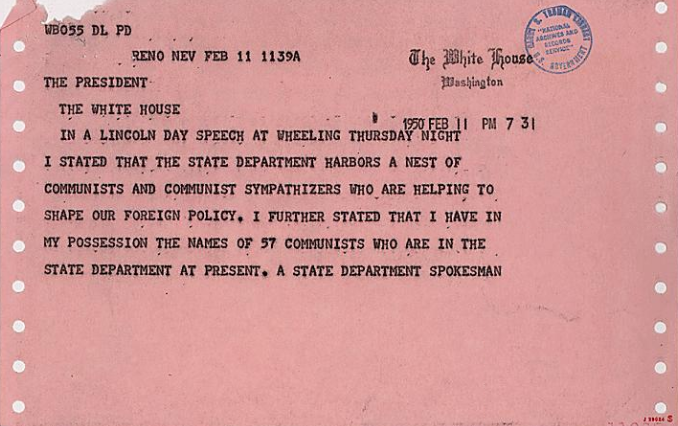

In the heat of the infamous McCarthy witch-hunts of the 1950s, which saw U.S. senator Joseph McCarthy gain national attention after claiming the American government was overrun with communist sympathizers, the homintern conspiracy theory soon engulfed America. With Americans fearful of the detonation of an atomic bomb and in a frenzy about politics being overtaken by communist defectors, the elusive figure of the homosexual—known but never seen in public; closeted but apparently everywhere—was ripe to exploit to inspire fear.

A telegram from McCarthy to President Truman warning of a “nest of communists” in government. (Photo: NARA/Public Domain)

Woods says that the anxieties around homosexuals in Cold War America take some of their origin in the social “cleansing” campaigns enacted in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, campaigns launched to eradicate homosexual men (and other “unwanted” individuals) from society. What proved most unnerving to many was that homosexual men were simultaneously “invisible”—apparently surreptitiously taking over branches of U.S. government, recruiting other men for their own “perverse cause”—and very visible in public life, known in the entertainment and film industries all at the same time.

This paranoia completely took over political life, lead to a report being commissioned in 1950 called “Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government.” The report claimed the “infiltration” of homosexuals to American political life meant that homosexuals would “inenvitabl[y] … attempt to place other homosexuals in Government jobs.”

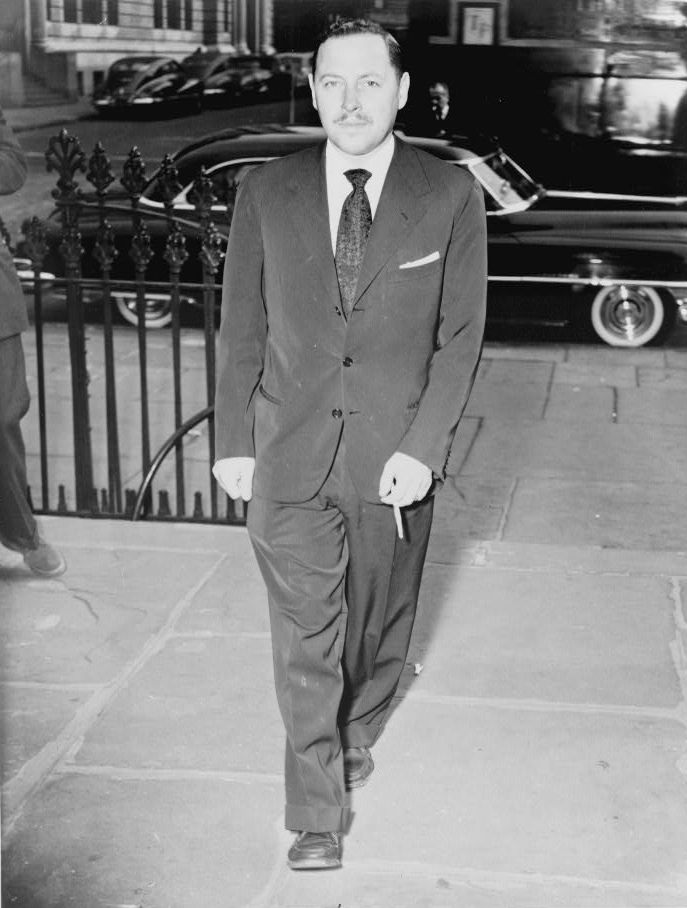

The backlash against homosexuals was only compounded by the growing visibility of gay men in public life, especially in the arts and entertainment industries, which only compounded the idea of an underground conspiracy of a “gay mafia.” Some of the most prominent playwrights of the 1950s were gay men, including Tennessee Williams, Arthur Laurents, and Edward Albee. Many critics were wary of the representations of American life offered by these “homosexual men.” In 1966, one New York Times critic mentioned the widespread perception that because these men were homosexuals their plays “present[ed] a badly distorted picture of American women, marriage and society.”

Playright Tennessee Williams in 1953. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-115075)

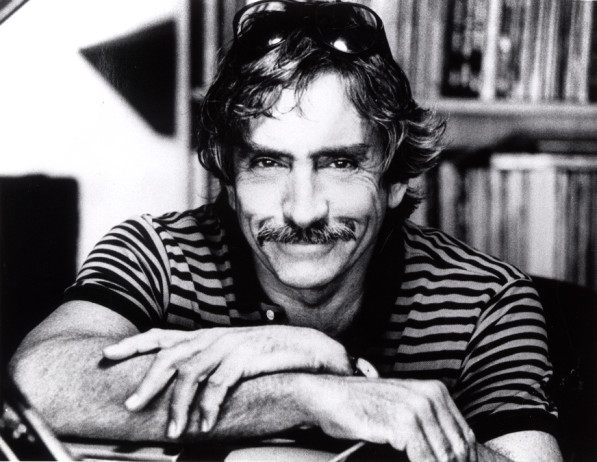

Similar claims were made about the number of “gay” men (closeted but commonly known to be gay) in Hollywood, including George Cukor, Montgomery Clift, Cary Grant, and Rock Hudson. Although these men were not “out,” rumors of their sexuality circulated widely in Hollywood and galvanized an image of Hollywood being overrun by gay men, many who allegedly wielded power and autonomy.

This kind of paranoia only extended to gay men. Unlike lesbians, gay men were seen as the more subversive threat because they had most public profiles as well as more likely to occupy positions of power in the entertainment industries.

Edward Albee. (Photo: Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries)

But some two decades later, with the groundswell campaigns for freedoms and visibility that eventually became the gay liberation movement, the homintern lost all currency in American life. The homintern was mostly an elusive figure, one that existed more in metaphor and the public imagination than in reality, since its origins were grounded in fear.

Thanks to the unparalleled recognition gay men enjoyed in the gay liberation movement of the 1970s, the homintern faded into myth. Today the homintern seems to be emblematic of another epoch from the 20th century’s closeted gay history.

All the same, the homintern’s awakening of fear in public life in 1950s America demonstrates an important narrative, reminding us there was a time when the idea of a “gay mafia” ruling Hollywood was a legitimate concern. If only they were still recruiting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook