Unearthing the True Toll of the Tulsa Race Massacre

99 years later, a community works with archaeologists to answer longstanding questions about a brutal tragedy.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.

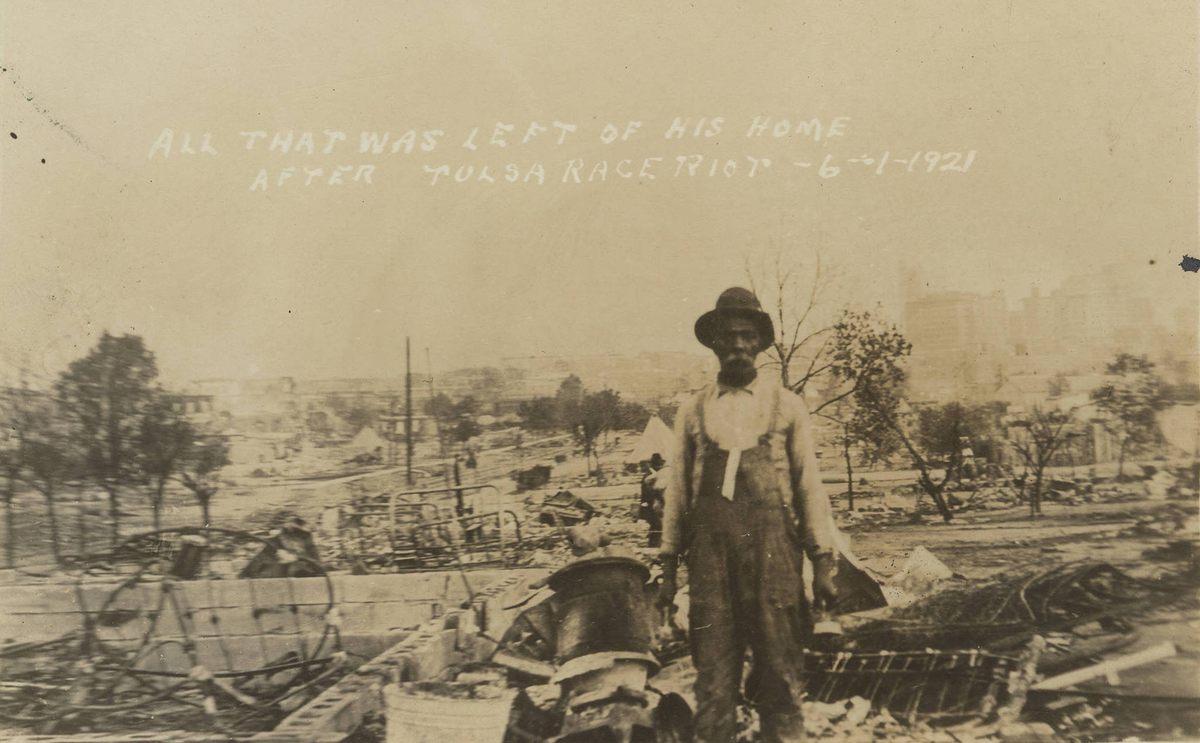

Just north of downtown Tulsa, Oklahoma, Greenwood once had one of the most successful African-American commercial districts in the country. By 1921, it was home to numerous black-owned businesses—beauty shops, grocery stores, restaurants, and the offices of lawyers, realtors, and doctors.

Residents caught silent films and musical performances at the Dreamland Theater. They could choose between two neighborhood newspapers. Greenwood offered a place to get bootleg liquor or attend church services. Although many people lived in the district’s spare wooden homes along unpaved streets, enough wealthy African American entrepreneurs called Greenwood home that it earned the nickname “Black Wall Street.”

All of that changed on the night of May 31, 1921. White mobs, armed with shotguns and torches, terrorized Greenwood in a horrific expression of racial violence.

The attackers killed an unknown number as they reduced a vital neighborhood to ashes. The official death toll recorded was 36, but some historians estimate the figure at around 300. No one was held accountable for the Tulsa race massacre. Its memory was both ignored and actively suppressed for years, despite the tragedy’s consequences for subsequent generations.

With the 100th anniversary approaching next year, Tulsans are grappling with how to acknowledge and honor the experiences of victims and survivors, especially as gentrification threatens to further erase Greenwood’s African American history. There’s also a national spotlight on the massacre and its aftermath—and not just because the violence has been dramatized in the HBO series Watchmen.

Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum announced that the city would search for the lost graves of victims in October 2018. A previous investigation took place from 1998 to 2000, in which researchers interviewed hundreds of local residents and conducted preliminary ground-penetrating radar surveys of potential grave sites. The results at that time were inconclusive and excavations never materialized. The renewed effort will probe longstanding oral histories that suggested the massacre’s untold dead remain buried in the city.

In December 2019, archaeologists presented new radar results that indicated possible mass grave signals for at least two sites. Early this February, a public oversight committee gave their blessing for archaeological excavations to begin. Trowels were supposed to break ground at Oak Lawn Cemetery on April 1, but the COVID-19 outbreak delayed the initial test excavation.

Those involved in the investigation have tried to temper high expectations and sensational headlines. The process could be slow and tedious, and the digs’ results could be inconclusive. But the search for remains in itself is unprecedented in several ways—including its extraordinary emphasis on community involvement.

“We had 300 years of slavery, we had 100 years of Jim Crow, we had thousands of people who died as a result of racist violence,” says historian Scott Ellsworth, who advised on the Oklahoma commission to study the Tulsa race massacre of 1921 and wrote a comprehensive account of the event called Death in a Promised Land. “But this is the first time ever in our country where a government at any level—federal, state, local—has intentionally gone looking for the remains of victims. That, to me, is astonishing.”

The Tulsa race massacre investigation doesn’t look like a typical archaeological project. While the mayor’s office is spearheading the effort, the city has ceded much control to the community. Local civil servants, activists, cultural leaders, and descendants of massacre survivors make up a public oversight committee that has been involved at each step.

In packed, live-streamed meetings, committee members ask archaeologists about how remains will be treated and whether DNA analysis is possible. They press for answers about whether Tulsa police lost or destroyed evidence on the massacre decades ago, and why the landowners of one cemetery have been slow to allow archaeologists to survey their site. (In late March, the graveyard’s owners finally granted permission for the investigation.) The members vote before any new phase goes forward.

The process is a far cry from more traditional ways of doing research, wherein a group of scholars comes up with their research questions, writes grants, secures permits, and collects data. In that approach, researchers might engage the community only once the work was underway.

But in academic spheres around the world, there is a push for new modes of research done with, by, and for communities that may have been previously treated like study subjects or whose stories and knowledge have been ignored, says Sonya Atalay, an archaeologist with the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

“The thing that I’m excited about is that I really see archaeology as leading the way in this area,” says Atalay. “In the last decade, this type of research has been growing and continues to grow.”

For example, some Indigenous communities are engaging in collaborative projects with both Native and non-Native archaeologists. The Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe recently found archaeologists at Central Michigan University to partner with to look into the history of the boarding school at Mount Pleasant, one of the many U.S. government–mandated institutions built in the 19th and 20th centuries to force Indigenous children to “assimilate.” Atalay is developing a portal to match communities with relevant scholars to facilitate these kinds of partnerships.

The search for mass graves in Tulsa is intended to build toward restorative justice and reconciliation, though it’s not clear yet whether the findings will affect political discussions on reparations for the descendants of massacre victims.

After the destruction, insurers refused to compensate many home and business owners; some rebuilding efforts were blocked. Of Greenwood’s 11,000 residents at the time, 9,000 were left homeless.

Calculating the loss to the families who saw their homes and livelihoods destroyed has proved just as challenging as confirming a death toll, says Alicia Odewale, a University of Tulsa archaeologist. Property loss may have amounted to between $50 and $100 million today, without taking into account the loss of heirlooms and family records, the loss of a sense of safety, the toll of displacement, or the stark inequality that exists in Tulsa today.

In December, when addressing a question on possible reparations, Mayor Bynum told the public oversight committee: “What this investigation yields in the end, I can’t say. The goal of this is to clarify the truth of what happened as best we can. If that leads to further action that needs to be taken on the city’s part, we’ll cross that bridge when we get there.”

Archaeological examinations of mass graves may help validate oral histories about the Tulsa race massacre and help identify victims. But it won’t change the fundamental truth about the tragedy.

“Whether the official death toll is accurate or whether it’s 150 or 300, this was a horrific incident of domestic terrorism and systemic racism,” says Hannibal Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District.

Johnson is on the historical context and narrative committee for the graves search. He’s also part of the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, a grassroots collective that is building a history center and revising school curricula related to the massacre. The commission is funding its own archaeological effort to look for the remnants of structures, foundations, and artifacts in historic Greenwood, and to map how the neighborhood changed over time. The group intends to conduct noninvasive geophysical surveys to identify sites of interest, then plan an excavation for 2021.

“We don’t want the narrative of the Greenwood community to be based solely on sites of death but [to also] incorporate sites of life, wealth, struggle, and family connections as well,” says Odewale, who is helping to lead the collective’s project. Odewale, who grew up in Tulsa, is currently the only black archaeologist living and working in the city with expertise in African diaspora archaeology.

“Digging into a certain area can reveal periods of change—loss and prosperity, destruction and growth—and these don’t have to be two separate stories of the Greenwood community, but allow us to see a clear connection between what happened in the past and what Greenwood looks like today,” Odewale says. “The great thing about archaeology is that it’s designed to have multiple truths be able to coexist in the same space.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook