The Wunderkind Writer Who Disappeared Without a Trace at Age 25

Barbara Newhall Follett was poised to be a force in 20th century letters. What happened?

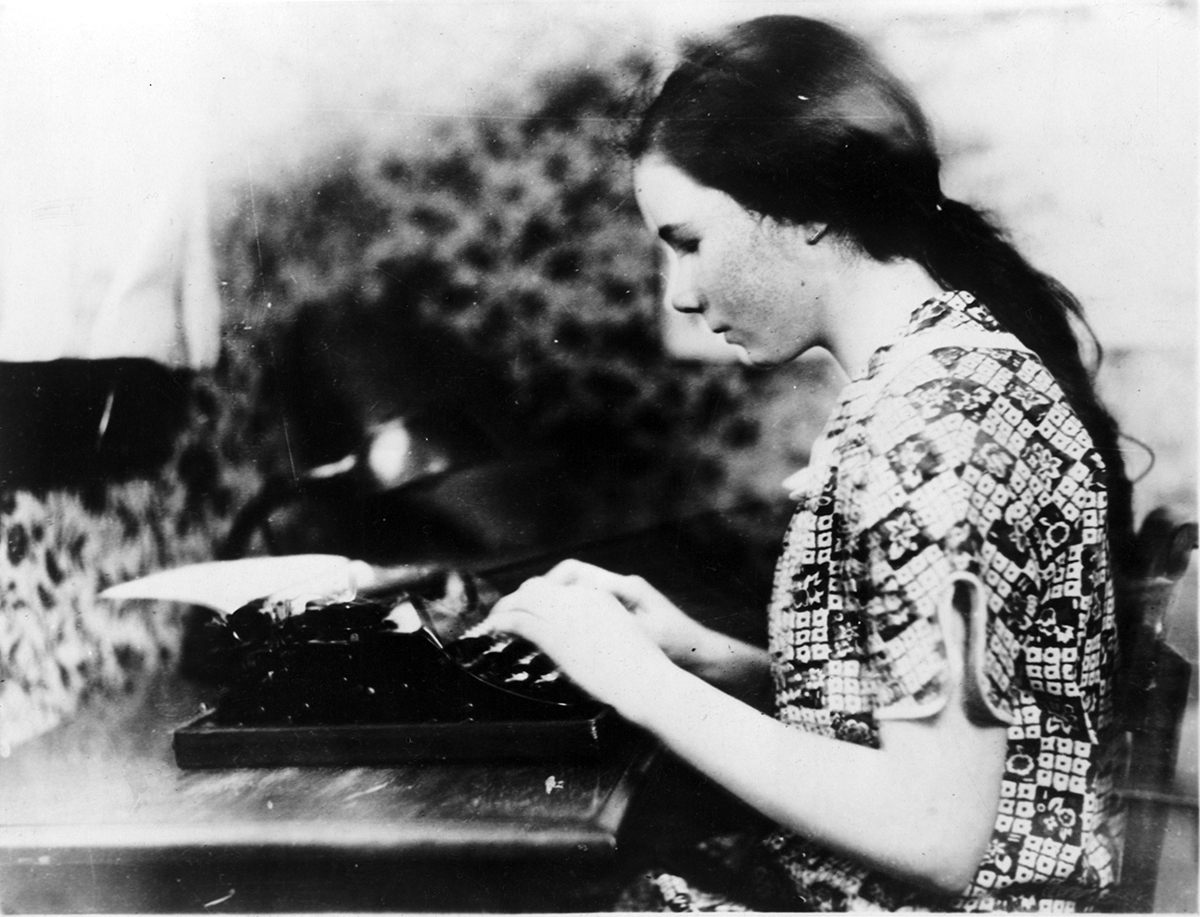

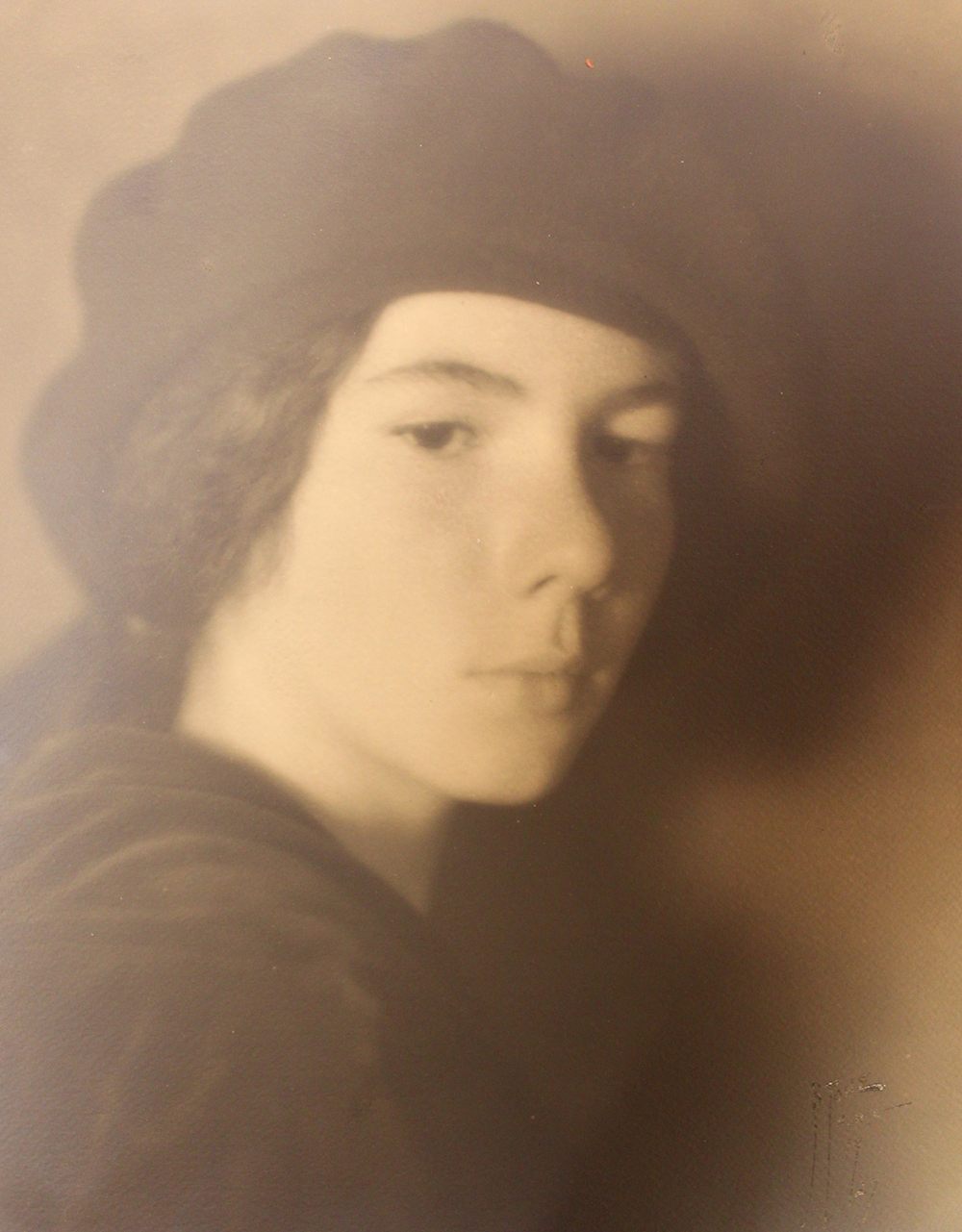

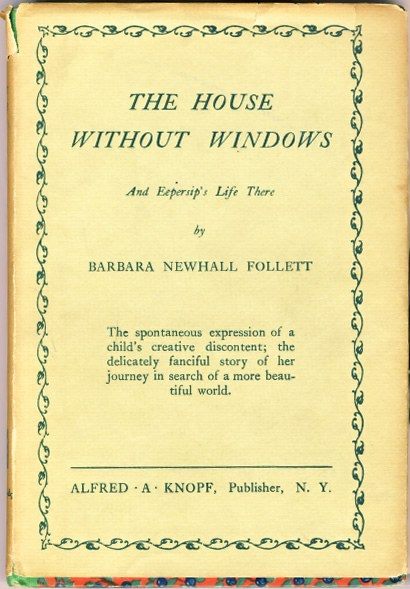

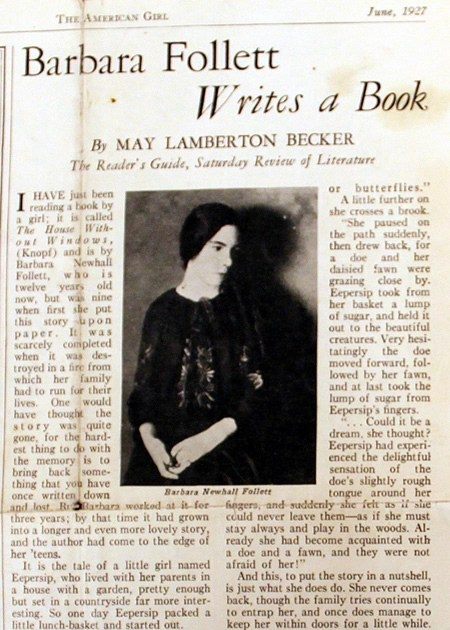

New England, winter 1923. A little girl sits alone in her room, staring through the window at the woods behind her house. She daydreams as most children do, but then she goes to her typewriter and she writes. By age 12, Barbara Newhall Follett has published her first novel—The House Without Windows—based upon the wonders of those woods. She is called a child prodigy, a literary luminary, a spirit of nature. So why have so few people heard of her or read her work?

For one, Barbara Newhall Follett disappeared without a trace when she was 25 years old.

After The House Without Windows was published to such acclaim, the young author was in hot demand for reviews and additional books. Of course, not all the critics adored her. A few were downright dismayed that she had been published and had a taste of literary success at such a young age: “What price will Barbara have to pay for her ‘big days’ at the typewriter?” wondered Anne Carroll Moore of the New York Herald Tribune. But Barbara wasn’t particularly concerned with having a “normal” childhood. Like many children who display intellectual giftedness or precocity, she didn’t seem that interested in children her own age. When one of her playmates criticized what Barbara considered fun (her writing), she wrote them a letter explaining, “You don’t understand why I have my work to do—because, at this particular time, you have none at all.”

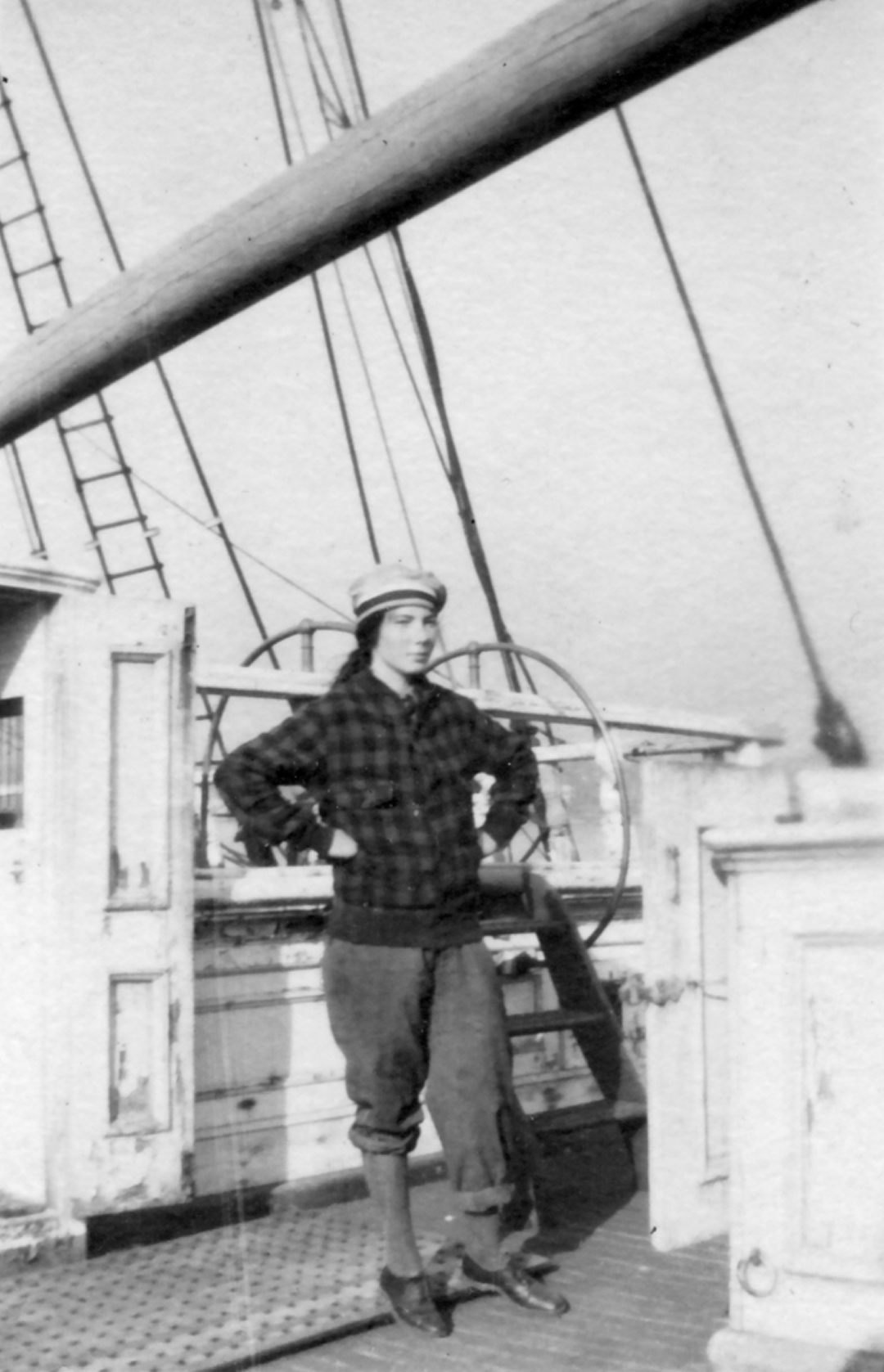

Throughout her teens Barbara continued to write, but she also turned her focus to what she considered the most prudent adventure of her life: to be a crewman on a ship sailing out to the Atlantic. At 14, her second book was published, The Voyage of the Norman D. During this time her father, Wilson, left Barbara’s mother for a younger woman. Barbara and her mother coped with the loss by sailing around the world, writing about their expeditions. They left Barbara’s younger sister, Sabra, behind. Don’t feel too sorry for Sabra Follett, though: she was also brilliant and went on to become the first woman admitted to Princeton’s graduate school in 1961.

Barbara and her mother eventually came back to New York with no money, and Barbara took a job as a secretary, which made her miserable. “My dreams are going through their death flurries,” she wrote to a friend. Without her father, who had been her encourager since she was small, the work began to dwindle. She found new inspiration in a young man she’d met named Nickerson Rogers. They traveled extensively—along the Appalachian Trail and in Europe—before marrying in 1934 and settling in Brookline, Massachusetts. For the first few years of the marriage she was happy, but somewhere around 1939, the marriage began to suffer.

“On the surface things are terribly, terribly calm, and wrong,” she wrote to a friend rather ominously, .”I still think there is a chance that the outcome will be a happy one, but I would have to think that anyway, in order to live; so you can draw any conclusions you like from that!”

What happened next was, whether she intended it to be or not, the conclusion: On December 7, 1939, after she and Nick had a fight, Barbara left their apartment on foot with just $30 and a notebook. She was never seen or heard from again. Nick didn’t report her missing for two weeks, and when she was listed as missing it was under her married name, Barbara Rogers — so the press didn’t pick up on the child prodigy turned gone girl. In fact, it wasn’t until her mother published a book in 1966 that the press got wind that the former child prodigy had disappeared. She’d been gone without a trace for over 25 years and no one knew.

Except, of course, her family. Over the years no sign of Barbara ever turned up, but her father, with whom she had never reconciled, wrote a letter imploring her to come home that was published in The Atlantic.

Today, Barbara’s half-nephew, Stefan Cooke, is the keeper of her mysteries. He’s published a book of her letters, runs farksolia.org which is dedicated to her work, and has tried to keep the spirit of Barbara Newhall Follett alive. Despite his extensive research, Stefan admits he can’t say with any certainty what happened to Barbara, though he thinks she very well could have started over again somewhere else, under a new identity. Though even that possibility, which would be true to Barbara’s dramatic and fascinating life, doesn’t sit entirely right with him:

“Whether she could have been so cruel as to not let her mother and sister and friends know whether she was living or dead is a good question,” he told me in an email, concluding “Maybe we’ll never know what happened to her. Thankfully she left behind her treasure chest of letters, short stories, poems, Farksoo (her invented language), and her superb lost novel, Lost Island—and her voice rings loud and clear throughout.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook