What It’s Like to Build a Traditional Japanese Automaton From Scratch

All you need is a good imagination. And a whole lot of patience.

In 2003, in the Wakayama Prefecture outside of Osaka, Japan, 51-year-old schoolteacher Kimiko Hirahata attended a festival for the local technical high schools, seeking inspiration for her lesson plans. Hirahata taught her students in a variety of media, from pottery and painting to lamp-making and calligraphy. But what appeared at the festival that day was something completely different.

“When I saw a doll carrying tea,” Hirahata says, “I was amazed.”

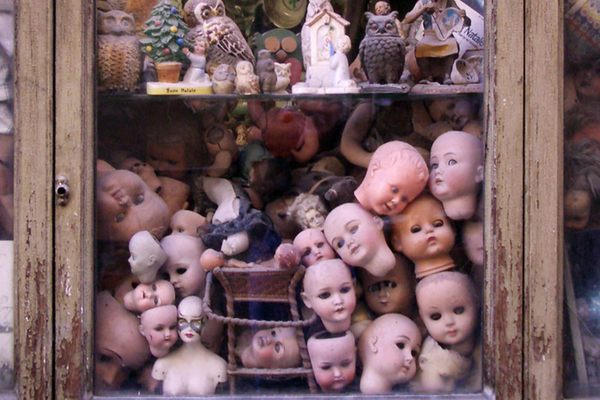

The doll was a karakuri—a traditional automaton. Like many other karakuri, the one Hirahata saw at the festival was entirely wooden, but also mechanical. A system of concealed gears (also wooden) within the doll allowed it, when cranked, to automatically perform a programmed task: in this case, to serve tea.

“When someone took the cup from the doll, it stopped. When they put the cup back on the saucer in its hands, the doll turned back on and moved to the start again,” Hirahata says. “I wanted to know the mechanism of it.”

The karakuri, as it turns out, wasn’t the work of any students but that of a local furniture-maker and autodidactic automaton-builder. Shigeo Tanimoto, then 68, lived about 10 minutes away. Inspired, Hirahata promptly headed over to pay him a visit.

Karakuri dolls got their start in Japan’s Edo period (which spanned the 17th to the 19th centuries). Perhaps the most popular were the “Zashiki” karakuri, which were employed for piquant parlor tricks, such as schlepping tea. Similar to Rube Goldberg machines in the meticulous time spent in their creation—and the rather frivolous ends those means achieve—the karakuri are a one-stop shop, with the capacity to conduct themselves and complete a task. But just one task.

For Hirahata and Tanimoto, it took years of commitment to make, ultimately, a very simple product. “I visited him to make the doll every Saturday. All parts were made by hand,” Hirahata says. “Furthermore, there is a rainy season in Japan. During this season or on rainy days, we couldn’t carve the wood because of the high humidity.”

The first doll they made—another tea doll—had five gears at its core, allowing it to move in an uncanny-valley manner. Hirahata estimates that it took them 20 days to make, working four hours a day. The body took 13 days to carve and prepare; the head, face, and hair another 17. The kimono alone required five days of construction. And so on. When Hirahata and Tanimoto started building the doll, it was May 2003. When they had finished, it was nearly 2007.

“I think that we took a long time to do everything,” she says.

The project was also rife with difficulties. Connecting the gears was a delicate process; too many turns on the crank and the gears would jam. Getting the automaton to pivot properly was also tricky, requiring a rubber band to operate smoothly. Every time the rubber band broke, Hirahata had to deconstruct the entire doll to replace it.

After the tea automaton they built a wooden archer, whose “engine”—again, wooden gears—was spooled up in a glass case on which the figure lay. As a second doll, stationed in the aforesaid case, mimicked the turning of the automatic crank, the archer on top of the box would nock and shoot arrows that had been custom-made for it. The archer karakuri took about three years to complete.

These days Tanimoto, now 85, is working on non-automatonic projects, like a lion mask. Once that’s done he and Hirahata—having formed an unofficial partnership—will spend time building traditional Japanese furniture together.

“He told me that he wants to make a writing doll if he tries to make another mechanical doll,” says Hirahata, who is now 68 (the same age Tanimoto was when the two first met). “When he tries to make it, of course I’ll try it with him too.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook