How Milwaukee Is Celebrating the Typewriter’s Long, Local History

In June 2023, Milwaukeeans celebrated 150 years of typewriter history.

The Milwaukee folk punk band Nineteen Thirteen has showcased the talents of various musicians over the years, from cellist Janet Schiff to drummer Victor DeLorenzo, a founding member of the chart-topping, Milwaukee-based Violent Femmes. Recently, though, the band featured a guest musician playing a lesser-known instrument—the typewriter.

“This was my first time playing the typewriter as a musical instrument, but hopefully not the last,” says poet Monica Thomas, who provided backup to Renee Bebeau’s percussion while typing a local news story on a vintage Remington, made in—you guessed it—1913. “I heard there’s a group in Madison organizing a typewriter orchestra, so there’s hope for next year.”

If you’ve never heard of a typewriter orchestra, that’s probably just the tip of the substantial iceberg of information you’re lacking about this intriguing machine. Another little-known fact about the typewriter: like the Violent Femmes, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, and TV’s Arthur Fonzarelli, the typewriter was born in Milwaukee. And for the first time, the city has composed the ultimate love letter to the typewriter in the form of a weekend-long 150th birthday celebration complete with Thomas’s typewriter musical talents.

“[The typewriter] is such a cool thing about Milwaukee, and I don’t think a lot of people know that” it was invented here, says Tea Krulos, an author, journalist, and co-organizer of QWERTYFEST MKE. “It hasn’t really been celebrated here at all.”

With the inaugural QWERTYFEST, Krulos and co-organizer Molly Snyder have worked to correct that error. Held from June 23 to June 25, QWERTYFEST was an inky paradise for collectors, artists, history buffs, and word nerds alike. The event featured live music, typewriting workshops, typewriter poetry ‘busking,’ and a local market featuring honey made by cemetery bees and a typewriter autographed by well-known typewriter enthusiast Tom Hanks. There was also brunch, open mics, and a scripted “Clackathon” performance. Developed alongside local theater company Quasimodo Physical Theater, the Clackathon featured fight scenes, crowd interaction, and a nefarious Chat GPT “villain.” The weekend culminated in a ceremony recognizing a signed decree from Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson declaring June 24 “QWERTY MKE Day.” The local celebration follows National Typewriter Day on June 23.

“We’re known for beer, we’re known for cheese, we’re known for motorcycles, and unfortunately, yes, we’re known for Jeffrey Dahmer,” says Snyder. “Yet most Milwaukeeans don’t know that the typewriter was invented here; the QWERTY keyboard was invented here. This is something that can raise the collective self-esteem of Milwaukeeans. Something amazing happened here.”

As much as QWERTYFEST was a celebration of nostalgia and antiquity, it also acknowledged the ongoing relevance of the original typewriter layout in modern communication and culture. With its nod to the QWERTY keyboard, named for the first six letters in the top left row of the first typewriter, QWERTYFEST is a reminder of the abiding power of a 19th-century technology that billions use every day to send reaction gifs, connect on dating apps, and comment on cute kitten videos.

“What’s really interesting is that right underneath our fingertips is this old-timey machine that we don’t think about as old-timey,” says science and technology historian Jason Puskar of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, author of the forthcoming book The Switch: An Off and On History of Digital Humans. “There are so few technologies that don’t change at all. It’s a Victorian interface in the middle of a high-tech computer.”

The QWERTY design was partly influenced by an earlier type of writing machine called the printing telegraph, Puskar says. The keyboards for these devices had black and white keys that resembled piano keys.

“Starting in the 1840s, they made these amazing machines that…had little piano keyboards, and on one end you would type in your message, and on the other end it would print out a spool of paper,” says Puskar. “This was a major influence on the QWERTY keyboard, because on the black keys you had the letters ‘a’ through about ‘m’ going from left to right, and then on the white keys, it wrapped around from right to left, from ‘o’ to ‘z.’ If you look at your keyboard now, that middle row is basically the black keys from the printing telegraph, with a few modifications.”

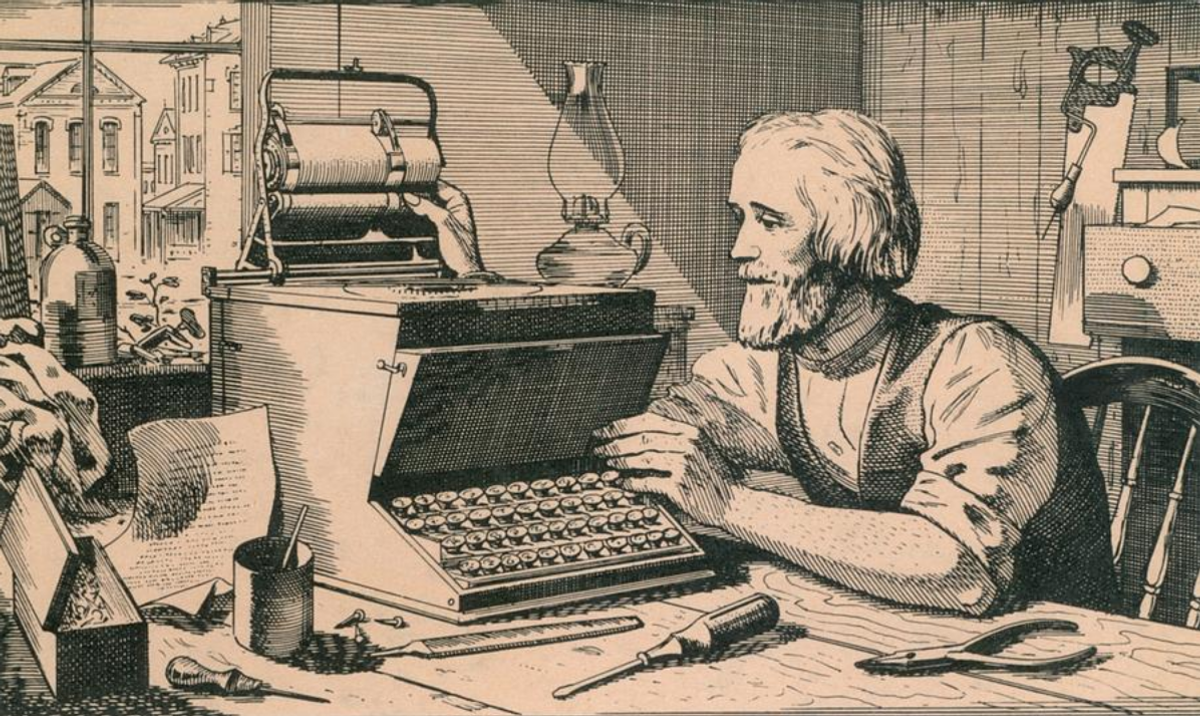

Christopher Latham Sholes, the typewriter’s inventor, was an intriguing hybrid of journalist, printer, politician, and father of 10 children. Born on Valentine’s Day of 1819 near Mooresburg, Pennsylvania, Sholes moved to Wisconsin in 1837, where he worked for his brothers’ newspaper in Green Bay. In the early 1860s, Sholes worked as an editor for The Wisconsin Enquirer, The Milwaukee News, and The Milwaukee Sentinel. He then became involved in politics and served in the state legislature. An appointment from President Abraham Lincoln to serve as collector at Milwaukee’s port led him to give up his position at the newspaper. During that time, Sholes began pursuing his interest in developing what eventually became the typewriter. Much of Sholes’ collaborative efforts with Soulé and Glidden took place at the Kleinsteuber Machine Shop in Milwaukee, which was something of a gathering place for local inventors.

“That machine shop was a place where people could come to use precision equipment that the shop provided,” says Puskar. “It was also a networking hub for innovators, inventors, tinkerers, etc. Sholes and Samuel Soulé met Carlos Glidden there—he was apparently working on a new kind of plow. Sholes and Soulé were working on an automatic ticket numbering machine there before he started on the typewriter.”

Sholes patented more than a dozen improvements and modifications to his earliest typewriter design. However he reportedly had difficulty raising funds for production, and 150 years ago, in 1873 he licensed the manufacturing rights to Remington and Sons.

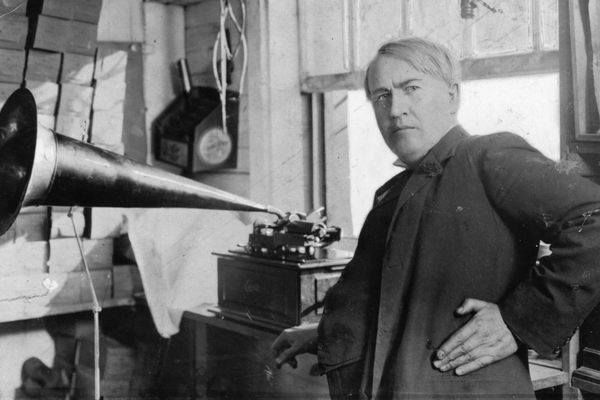

Although typewriters became standard equipment in offices, the advent of computers and word-processing technology in the 1980s drove the typewriter out of widespread use. But even as modern computers took shape, the QWERTY keyboard layout remained largely unchanged, despite several attempts to come up with a more efficient design. Puskar isn’t entirely sure why.

“Why do we drink wine from special glasses with tall stems? They don’t serve a practical function, and they’re kind of inefficient,” he says. “It’s a pain to load into the dishwasher. Yet we like it, and it feels wrong to change it. I think it’s okay to admit that even our highest technologies are influenced by a certain degree of cultural fondness.”

The QWERTY keyboard layout may have resisted decades of change to become seamlessly incorporated into modern hardware, but the typewriter has benefited from a different type of “cultural fondness”—nostalgia and romanticism.

“I think the more we advance technologically, the more we appreciate the simplicity of what was,” says Snyder, who writes for OnMilwaukee Magazine and has permanently commemorated the first-ever QWERTYFEST with a different type of ink—a tattoo of a typewriter. “We perceive the world as getting scarier and less kind, at times. It’s nice to be able to revert back to things that remind us of simpler times.”

Snyder, whose first published poem was pecked into existence on a family typewriter when she was a child, became hooked on typewriters at about the same time she was falling in love with writing. She and her husband have a special shelf designated for her collection of typewriters, or, as enthusiasts call them, ‘typers.’ Snyder has also found that her own children, who grew up in an age where phones take pictures and robots perform surgery, were instinctively drawn to the almost toylike physicality of typewriters. “When they were younger and I was trying to work, I used to set them up with typewriters and we would play a game called ‘office party.’ They loved it.”

There are almost as many ways to love typewriters as there are typewriters themselves. Thomas, amateur typewriter musician, poet, and enthusiast, offers typewriter repairs, transportation, and community resources through a Facebook page called Milwaukee Typewriters. Despite having approximately 100 typers, Thomas does not consider herself a “collector.”

“If I were to call myself a collector, I’d say I am more the thrift store variety collector, versus the hard-to-find, antique quality collector,” says Thomas. “What really got me started in this was a drive to keep typewriters from being neglected and get them into active use again.”

There is a bittersweet origin story to Thomas’s quest to “rescue” typewriters. Her parents threw away her very first typewriter when she left home. “It didn’t occur to them that I’d want to keep it,” she says. “I think that planted the seed for me wanting to get another typewriter for myself, but also to try to save as many as possible. I wanted to raise some awareness that these things are built to last.”

For artists, typewriters are something of a perfect medium—typewriters leave a lasting and charming visual product. There are even visual artists who specialize in typewriter-produced landscapes, animation, and portraits of Tom Hanks, who seems to pop up in typewriter culture as often as Forrest Gump showed up in the events of the 20th century.

QWERTYFEST honored the typewriter’s artistry not only through Thomas and Nineteen Thirteen’s performance, but also through attractions such as typewriter “busking”’ provided by poets such as Andrea Becker. Becker, who traveled from Dakota, Iowa for QWERTYFEST, is a typewriter poet, and types spontaneous poems on request. The recipient of the poem gets to hear it read aloud and is given the typed poem as a memento.

The typewriter is perhaps best known for the role it once played in the world of business, particularly in terms of women entering the office environment. QWERTYFEST celebrated this history as well, although it also turned a critical eye on some of the gender disparities that are part of the typewriter’s lasting legacy.

In her QWERTYFEST presentation, “Women’s Complicated History with the Typewriter is not Black-and-White,” Snyder discussed how the typewriter ushered women into the corporate world (men apparently thought early typewriters looked too much like sewing machines and therefore avoided typing jobs), even as it introduced and solidified the gender pay gap.

Snyder says women were eager to seize these opportunities since they paid more than the other jobs available to women without college degrees. However, this turned out to be a defining moment in establishing inequality in the workplace.

Her talk led to a truly serendipitous moment for Snyder. “I ended up making a true connection with an 85-year-old woman who actually lived through what I was talking about in my presentation,” says Snyder. “She and I are working on a larger project for next year[’s QWERTYFEST]. I’ll talk about the history, and she’ll discuss her personal experiences.”

Snyder and Krulos were both pleasantly surprised by the wide range of QWERTYFEST attendees, from older enthusiasts who had been typing for years, to people who had never used a typewriter before. “I was really struck by the diversity of the age range and different types of people,” Krulos says. “They showed up from all walks of life, because they have an interest in this history and these machines.”

Snyder was pleased with the success of the inaugural event, but had a message for one of the many famous enthusiasts to whom they sent typewritten invitations to QWERTYFEST.

“We let it slide this time,” she says, “but Tom Hanks is not getting off the hook next year.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook