The Cute Critter Rewriting Our Understanding of Prehistory

Before cows and chickens, cuscuses may have been the original livestock.

At first glance, the cuscus looks like a cross between a cat, a monkey, and a Furby. An herbivorous marsupial found in New Guinea, Australia, and the surrounding islands, it has sharp claws, a tail that wraps around branches, and forelimbs that look eerily like human hands. The babies are also unreasonably cute.

“They like to wrap their tail around you and curl around,” says Shimona Kealy, a researcher at Australia National University who, as a Ph.D. student, once handled young cuscuses. “My supervisor was trying to take a photo, and I was just there being like, ‘Can’t we take it home?’”

Kealy doesn’t endorse capturing baby cuscuses. But, as she explains, “that’s a really common thing throughout Indonesia, Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea.” People hunt them, and if they catch a mother, they keep the young. “You’ll see young boys that run around the village, and [the cuscus] will just sit on their shoulder.”

Kealy grew up in “the bush,” she says, in a town of 1,000 people, a three-hour drive north from Sydney. The first in her family to attend university, she now studies the early history of humans and cuscuses in the Asian Pacific Islands. She’s published papers on ancient rock art, fishhooks, and obsidian networks. And in a paper that appeared last year in Australian Mammalogy, she and six researchers combined archaeology, paleontology, and genetics to help resolve the evolutionary history of cuscuses.

Studying cuscuses and humans might seem like an odd pairing. What can a tree-loving marsupial teach us about human history?

As it turns out, quite a lot. The relationship between humans and cuscuses goes back millennia, preceding the agricultural revolution. And the depth of that relationship challenges some of our most fundamental beliefs about human history.

In a 2017 article for The Guardian, the anthropologist James Suzman summarized what he considered a major difference between humans before and after the Agricultural Revolution that occurred 10,000 years ago. Before the Revolution, he wrote, “hunter-gatherers considered their environments to be eternally provident, and only ever worked to meet their immediate needs. They never sought to create surpluses nor over-exploited any key resources. Confidence in the sustainability of their environments was unyielding.”

“In contrast,” he went on, “Neolithic farmers assumed full responsibility for ‘making’ their environments provident.”

This is a popular view. We imagine that, before the Agricultural Revolution, humans hunted and gathered and nothing more. They accepted whatever their environment gave them. Then, as the Ice Age ended, their attitudes changed. They became clever enough to manipulate the environment. They started to plant, tend, and irrigate.

Is this story true? For decades, archaeologists have been quietly unearthing a heap of evidence suggesting not. Humans, it seems, did not suddenly switch from trusting foragers to savvy environmental engineers. Rather, the impulse to cultivate runs deep, possibly as deep as the origins of our species. And the most impressive, and overlooked, evidence concerns cuscuses.

For New Guineans and their neighbors, cuscuses represent spectacular bundles of resources. They provide protein. They can make fun companions. Their fur can be cut into strips for headbands or worn around the waist like a skirt. Before metal tools, their teeth were probably used to cut tortoise shells. This economic importance imbues cuscuses with sacred and social significance. For the Nuaulu of Seram Island, the cuscus joins the deer, cassowary, and wild boar to form a category of special animals called peni, which are shared widely and consumed only after making an offering to ancestral spirits.

The cuscus presence in the Asian Pacific Islands seems like a providential gift. Without cuscuses, Kealy explains, on most of the islands “your options for terrestrial protein sources are very, very limited.” You might come across small lizards, and “if you’re lucky, you have some giant rats. That’s it.”

Cuscuses make life easier. They’re simple to hunt and always seem bountiful. And, as Kealy points out, “they seem to be okay with a kind of semi-captive lifestyle.” After capturing cuscuses, Asian and Pacific Islanders keep them in bamboo or wire cages, fattening them up on fruit and root vegetables and periodically letting them loose to browse on their own.

The existence of cuscuses seems all the more serendipitous (for hungry humans) because everything about the environment suggests they shouldn’t be there. Many of the islands are remote. It’s hard for animals, especially meaty ones that neither fly nor swim, to ever reach them. The islands are small enough that a bad year might kill off a species with no chance of recovery. Some are volcanic, with regular eruptions purging the land of all life.

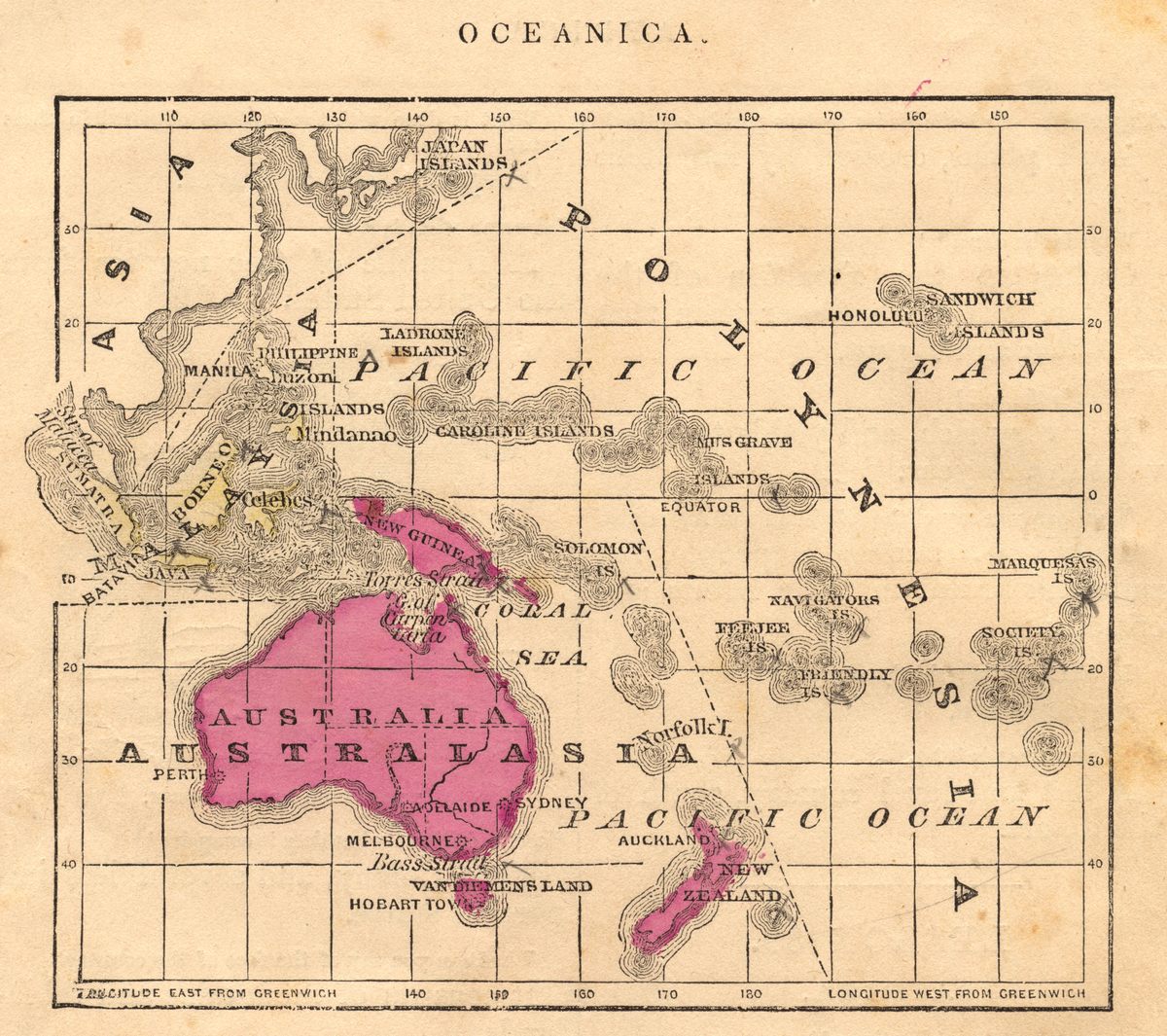

Yet cuscuses flourish. After a volcano exploded on Long Island 400 years ago (in the South Pacific, not New York), killing almost everything on it and ejecting a Hungary-sized cloud of debris over New Guinea, the animals that successfully recolonized it included birds, bats, dragonflies, and, somehow, cuscuses. Today, cuscuses range from Sulawesi in the west to the Solomon Islands in the east—a latitudinal stretch that exceeds the distance between Austria and China and, excluding possums introduced to New Zealand, is the greatest of any group of marsupials. In fact, it is because their distribution is so broad that cuscuses—rather than koalas or kangaroos—were the first Australasian marsupials encountered by Europeans.

How did cuscuses become so far-flung? Some researchers suspected human involvement, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that the story started to crystallize. On island after island, archaeologists discovered that cuscuses were newcomers, their arrival coinciding with human occupation. They got to the Solomon Islands roughly 8,500 years ago. They got to Timor about 3,000 years ago. These are blinks in archaeological time. If we imagine these islands have been next to New Guinea for a day (rather than for millions of years), it isn’t until 11:58 PM that cuscuses finally leap over, incidentally when humans, who have a penchant for catching them, also appear on the scene.

By studying recent migrations, researchers infer what likely happened in prehistory. New Guineans and their neighbors didn’t just capture cuscuses—they raised them, moved them, and introduced them to empty habitats. After the volcano killed everything on Long Island, a man named Ailimai brought over northern common cuscuses to replace the lost population. Something similar seems to have happened throughout the Asia-Pacific.

“I was completely surprised,” says Tim Flannery, an explorer and mammalogist who discovered and summarized some of the archaeological findings. “I had assumed these were all natural distributions, you know?”

The biggest surprise came on New Ireland, a shotgun-shaped island 600 kilometers from New Guinea. In the late 1980s, Australian archaeologists discovered cuscus bones there in sediments dated to before 20,000 years ago. The bones themselves haven’t been dated—and depending on their preservation, that may never be possible—so, Flannery puts a conservative estimate of translocation closer to 12,000 years ago.

Regardless of which date you go with, the implication is the same: Thousands of years before plants were domesticated in New Guinea, people were managing cuscus populations. Cuscus translocation is arguably the oldest-known example of animal management in history, preceding not only the Agricultural Revolution, but the earliest evidence of pig, cow, and sheep cultivation, as well. Since they were probably owned and traded, cuscuses may even represent the first livestock in documented history, although some archaeologists restrict the label to fully domesticated animals.

“It doesn’t really fit very well into the neat linear narrative that’s often presented when we think of animal domestication,” says Max Price, an archaeologist at MIT.

The way in which Asian and Pacific Islanders raised, managed, and transported cuscuses challenges the supposed boundary between prehistoric foragers and modern cultivators. Non-agricultural peoples do not passively accept whatever their environment offers. They can arrive on an island that only has giant rats and recognize it would be better if it had cuscuses. They can catch a batch of those critters and transport them in a canoe. And they can do so again, and again, and again.

Anthropologists have uncovered other evidence suggesting a penchant for management among non-agricultural peoples. They discovered efforts to cultivate cereals at a 23,000-year-old site in Israel. They discovered that hunter-gatherers managed boars in prehistoric Cyprus and Japan. And they’ve come to appreciate the diversity of management systems used by foraging peoples in the Americas, from the irrigation systems of the Owens Valley Paiute to the clam gardens of the First Nations peoples in the Pacific Northwest.

So, what does the history of cuscuses tell us about humanity? Cuscus translocation is a microcosm of the human story. We live not just by adapting to our environment, but by adapting our environment to suit our needs. We set fires, level ground, and move animals. We irrigate deserts and domesticate rainforests. We burn fuel and spew gases and invite climate catastrophe. We push animals into cities and rub shoulders and saliva with them and spark a global pandemic. When New Guinean hunter-gatherers carried cuscuses in canoes, they were engaging in a deeply human impulse, one at the root of our greatest failures and successes.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook