A Century Ago, Wood-Eating Worms Devastated San Francisco Bay

The battle against them is still being waged today.

On March 2, 1920, 1,000 feet of wharf came crashing down into Northern California’s Carquinez Strait, just northeast of San Francisco Bay. The problem wasn’t shoddy construction—the wharf belonged to the Union Oil Company—nor was it a storm. It was an invasion.

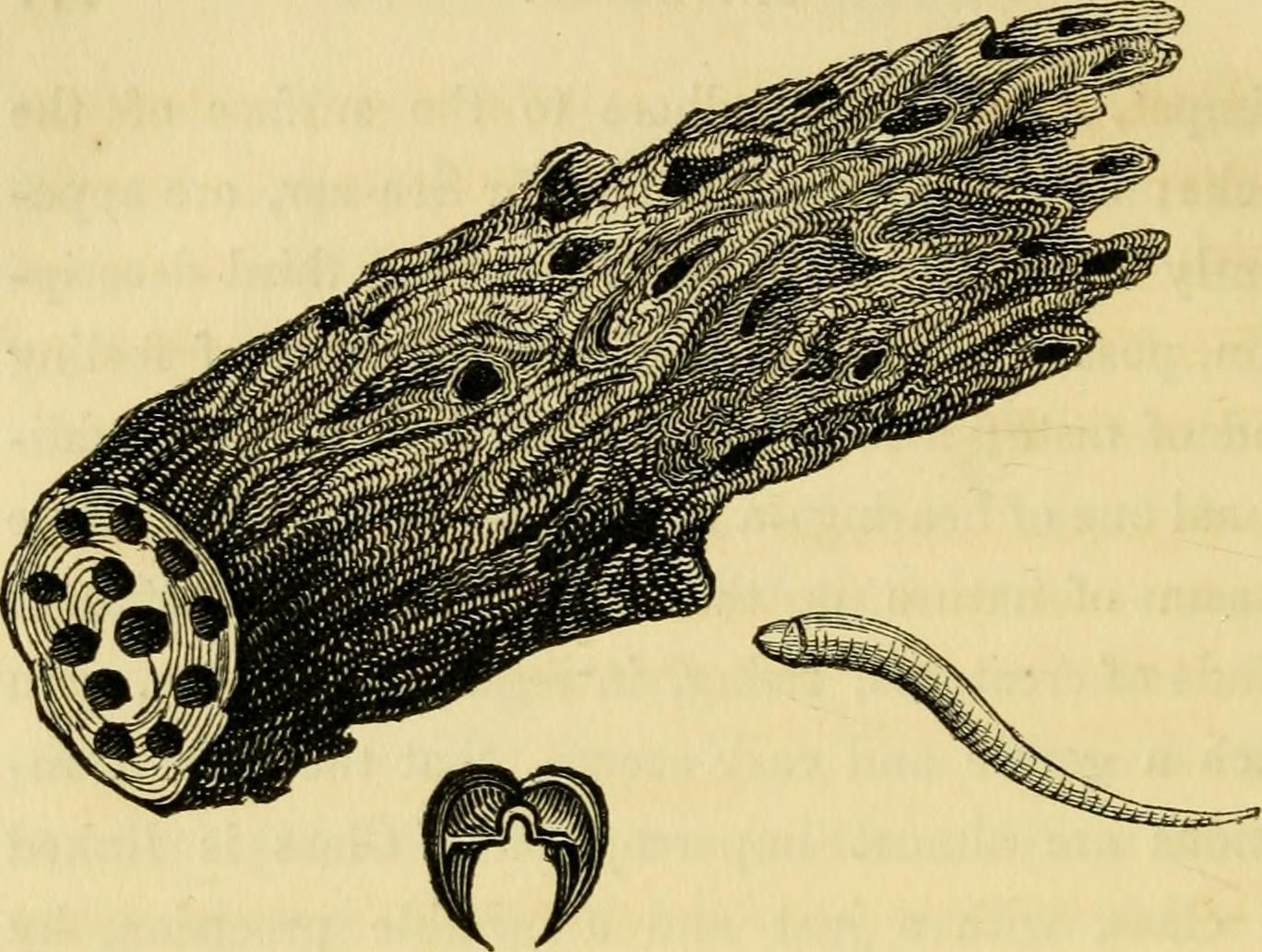

The invader was the notorious Teredo navalis shipworm. T. navalis is a worm in name and appearance only. It is actually a saltwater clam, with a bivalve shell at one end that anchors a contorting, tapering line of tubular flesh. They feed—obsessively, aggressively, reflexively—on wood that finds its way into the ocean, rendering it unrecognizable, a honeycombed sponge where there was once something solid. Though shipworms have been around since long before we took to the water in wooden boats, our maritime journeys have helped spread them all over the world. We also sink a great deal of wood, in the form of piles, into the water, offering shipworms a rotating smorgasbord that helps them become established in some of our most heavily trafficked maritime areas.

San Francisco Bay is one of those areas. The city had grown during the second half of the 19th century to become one of the world’s premier port cities, handling six million tons of international goods in 1900. By eight years later, 23 piers lined the waterfront. One of them, Central Wharf, stretched 2,000 feet into the bay, as if beckoning the mollusks to feed.

The journal Nature estimated the damages caused by shipworms in the bay at $25 million between the years of 1917 and 1921. Conservatively, that’s more than $300 million today. By the end of 1921, “the bulk of structures with untreated pile had been destroyed,” reported Nature, “sometimes carrying buildings with them.” Andrew N. Cohen, an environmental scientist with the Center for Research on Aquatic Bioinvasions, writes that the casualties included loaded freight cars from Union’s railroad dock, the Municipal Wharf and Customs House for the town of Benicia, “three grain warehouses, one highway and two railroad bridges and twelve ferry terminals.” For two years, Cohen writes in a 1997 conference paper, the devastation ensued at the rate “of one major wharf, pier or ferry slip” every two weeks.

Given that cost, maybe it’s poetic that shipworms likely arrived with Gold Rush prospectors. In 1849 alone, the year gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, 650 ships arrived in the bay, and many were just abandoned there. In the space of a decade, Nature reported, “many wharves were derelict and tottering from their attacks.” But that was just the beginning. The attacks, likely carried out by a Pacific shipworm called Bankia setacea, didn’t make it too far north. In 1914, however, a more pernicious invader arrived from the Atlantic. Around that time, a long drought made the bay saltier and more hospitable to T. navalis, and by 1919 it had proliferated to an astounding degree. The ensuing battle between mollusk and human would be hard-fought, and though the Port was far from unscathed, it survived in the end—a scarred witness to one of history’s most quietly vicious armies.

Carl Linnaeus—the 18th-century Swedish scientist who developed the system of giving each organism two Latin names—called shipworms, apocalyptically, Calamitas navium. He understood that the mollusks had terrorized mariners and boatbuilders for centuries, poking ships full of tiny holes that can weaken them or sink them outright. In the Iliad, Greek soldiers tarred their fleet with pitch before setting off for Troy to protect themselves from such hazards. Good thing they did. The Viking Saga of Erik the Red, dating to the 13th century, holds shipworms responsible for sinking and drowning the poor explorer Bjarni Grimolfsson, thought to be the first European to see the North American mainland. They got to Columbus, too—two of his ships in 1503. Some believe that the ship that inspired Moby Dick, Essex, was weakened by shipworms before a whale took it down. Same with the Spanish Armada, which may have brought the stowaways with it from warmer waters. Dan Distel, a shipworm biologist at Northeastern University’s Ocean Genome Legacy Center, shared what an old professor told him with The New Yorker: “If it wasn’t for shipworms, we’d be speaking Spanish today.”

T. navalis doesn’t require much to wreak havoc: sufficiently saline water, plenty of wood, and a little bit of company (and maybe not even that). Unlike many marine creatures, they are internal fertilizers, meaning their larvae gestate inside an adult’s body, allowing them to mature in relative safety from predators. They are protandrous hermaphrodites—born male and then maturing into hermaphrodites—that can sometimes even self-fertilize, and adults can release tens of thousands of larvae over the course of a lifetime. All of this allows new mollusks to be born right into the same wooden structures their parents occupy instead of braving the currents and hoping they land on a new food source. “Ideally, it can be just one animal,” says Distel, “one larvum settling on the wood is enough to start a new population.” And those populations can grow fast.

On February 6, 1921, the San Francisco Chronicle noted, seemingly with grudging admiration, the worms’ ability to fill 100 square feet of wood with more than 100,000 tenants—that’s 1,000 individuals per square foot. “Menacing all unprotected and untreated timber structures throughout San Francisco bay,” wrote the Chronicle, “the teredo sallies forth on its errand of destruction against pilings, docks, ferry slips and wharves. These worms, some of which are two or three feet in length, are so active in their work that it is possible to hear the rasping of their tools on the wood by placing the ear against the exposed top of the pile.”

Distel can confirm that the boring is indeed audible, the sound of shells “covered with tiny teeth” drilling incessantly away at an unlucky pile. The shells, he explains, have openings that allow each worm to stick its foot out of one end and the rest of its body out of the other. Using its foot like a “suction cup” on the wood, the worm then proceeds to rock the two halves of its shell “back and forth in a kind of scissor motion,” scraping away at the wood and grinding it down into edible particles. “They spend a lot of energy chewing,” Distel says with a laugh.

A kind of ingenious, if destructive, engineer in its own right, the shipworm mystified the human engineers deployed to thwart it. Early attempts at managing the borings involved creosote, a poisonous coating that can repel the mollusks. But creosote only penetrates a couple of inches into a pile, leaving the interior vulnerable, and possibly exposed through a crack or untreated area. The Chronicle wondered whether the creosote might just be “an appetizer” for them, and summarized its frustration with a poem: “you may dope, you may paint the piles as you will, but the teeth of the shipworm will gnaw at them still.”

Enter H.L. Demeritt, an engineer with the U.S. War Department, whose alternative for dealing with shipworms was dynamite. He oversaw experiments in Carquinez Strait that attempted to blow the worms out of the water, one blast of 60 percent nitroglycerine powder at a time. The results were predictably negligible. Demeritt was part of the San Francisco Bay Marine Piling Committee, which in 1927 published a mammoth report on its shipworm research and claimed to have surveyed roughly 90 percent of the area’s 250,000 piles. All told, the committee tested some 45 chemical compounds, and eventually established creosoting and construction guidelines that finally helped to stymie the shipworms, and downgrade the situation from a crisis of “epidemic severity” to a major, if manageable, nuisance.

This all means that this battle has never truly ended. Bruce Lanham, who worked with the Port of San Francisco’s pile-driving crew for over 25 years before retiring in 2016, recalls encountering piles with damaged coatings or tiny cracks: “Oh God,” he says, “these little devils would just—they were just insidious, they would just go to work.” Once, Lanham says, he was about to label a pile 80 percent stable when his index finger fell into a tiny hole. The log turned out to be nearly hollow. It looked right, Lanham says, but “Man, this thing was gone.”

Toxic creosote has never been a perfect option, even when it works. Lanham says the chemical routinely caused his skin to peel—not an ideal effect for something being placed in a major body of water. Creosote has not been applied to pilings since the 1960s, says Carol Bach, who does environmental work for the Port of San Francisco, but the stuff is still leaking from older wooden structures all around the bay. While newer piles tend to be made of concrete, Bach says that a total overhaul is impossible, as much of the Port now falls within the protected Embarcadero historic district. (Some mollusks can damage concrete, too, though not so severely.) So instead, the Port deploys divers to swathe piles in protective plastic wraps that both spurn borers and contain chemicals. It’s the best, most environmentally conscious thing to do at the moment, and the shipworms aren’t going anywhere. “The dive crew at the Port of San Francisco’s got job security that just won’t quit,” Lanham explains.

Soon other places, once thought beyond the reach of T. navalis, are going to face the same challenges. The Baltic Sea, for example, has in recent years seen a curious influx of shipworms, possibly due to climate change and increased salinity. There aren’t so many wooden ships any more, but the Baltic’s cold water has preserved thousands of historic shipwrecks that had so far been spared the depredations of the bivalves. It’s like the shipworms, ever restless, are planning to make up for lost time by going after ships they missed on the first go-round.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook