How an Irish Bog Got a Second Life as a Sculpture Garden

At Lough Boora Discovery Park, visitors can meditate on the important role of these wetlands in Ireland.

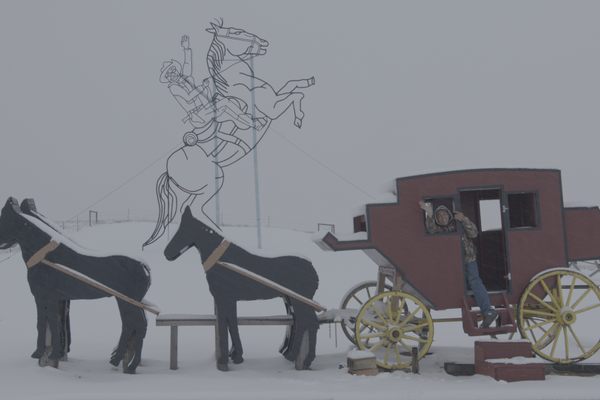

In the middle of Ireland, about halfway between Dublin and Galway, a large rusting, yellow train sits on a track. Its engine is hooked to six cars and a tea hut caboose, dented from their years of hauling fuel that was sliced out of bogs. During their life as industrial mining equipment in the 1950s, the train cars were piled with carbon-rich black peat soil for the Irish company Bord na Móna. The tea hut caboose is where the company’s rail line workers took their break and had a drink. But that was back when this park was an actively mined peatland.

Seventeen years ago, the train found its final resting place and is now called the “sky train” by visitors who see it as they enter Lough Boora Discovery Park’s sculpture trail. Today, opportunities to birdwatch, fish, walk, and cycle along more than 20 miles of trails dotted with dozens of sculptures brings 100,000 visitors to Lough Boora Discovery Park each year. The history of Lough Boora Discovery Park before its days of art and trails provides an interesting lens into a part of Ireland’s landscape that has deeply shaped the Irish people and way of life: bogs.

Cathy Kerwin, a 17-year resident of the community near Lough Boora Discovery Park, walks the wetland trails every morning with Jaxson, her Husky-Border Collie. She loves the natural quiet and the bird songs she hears along the trails.

“What I’ve discovered is that the sounds nature makes have the ability to quiet my mind,” says Kerwin. That peace along with the possibility of unique interactions with nature is what gets her out the door and into the park each morning.

“When a dragonfly landed on my hand for five minutes and I could look at it and hold it up to my face, I can’t put a price on the value of how I felt in that moment,” says Kerwin. She appreciates that the park in its post-industrial state attracts wildlife and many different types of birds to repopulate the formerly dry, barren peat soil.

Before its transformation, Lough Boora Discovery Park was part of Bord na Móna’s Boora Bog Complex. Looking outside the boundaries of the park, the Boora Bog Complex is vast and industrial peat mining is ongoing. The park encompasses about 5,000 of the 25,000 acres that were drained, stripped of plants, and mined for peat.

Those acres were part of the 20 percent of Ireland once covered in peatlands, a wetland category that includes raised bogs, blanket bogs, and fens. Boora Bog Complex was a network of raised bogs, which are 10,000-year-old glacially formed lakes that over time filled with moss and swelled up into a dome. Bord na Móna drained them, deflating the dome by slashing it with long ditches to draw out water, and then mined the peat.

Black peat soil is still ubiquitous in Lough Boora Discovery Park’s landscape, which used to be several feet tall in the stuff. You can grab a handful of peat and inspect its wet, organic contents, squishing thousand-year old moss remains with your thumb and finger. Rich black peat soil is a precursor to coal and it is Ireland’s most prolific fossil fuel.

Turf is what the Irish call peat when it is harvested to burn for fuel, something that has been documented as early as the seventh century in Ireland. For hundreds of years, it sustained the fire under kettles of potatoes in rural homes when an open fireplace was a central feature of thatched stone cottages. Bord na Móna (Irish for Turf Board) was established as a semi-state company in 1946 to industrialize the harvest of turf and use it to electrify Ireland. Turf continues to be a source of fuel in homes and power plants today in Ireland. In 2018, peat was burned by three power plants to generate seven percent of Irish electricity. As of 2016, 90,000 Irish households continued to toss turf into their stoves as their primary source of home heating.

Two of Lough Boora Discovery Park’s tallest sculptures memorialize peat’s role as fuel, flexing toward the sky and mimicking the cooling towers of the decommissioned peat-burning Ferbane power plant. During peak mining, one million tons of Boora’s peat was removed each year to supply the plant and a nearby factory that made peat briquettes for home use. A few hundred feet down the trail from the sculpture towers, the old steel “tippler,” a huge cylinder that dumped load after load of peat-filled train cars into a stockpile at the power plant, is now an outdoor shelter. Covered in native plants, the tippler’s roof pays simultaneous homage to the ecosystem that used to live here and the industrial inventions that scraped it away.

Plants, including acid-loving sphagnum mosses and the carnivorous sundew, and birds such as the ground-nesting curlew, need the bogs to survive but the habitat is dwindling. Across Ireland, around 85 percent of peatlands are in degraded ecological condition. Less than one percent of raised bogs, the type mined at Boora Bog Complex, are still actively growing.

“We need to start appreciating what we have before we don’t have it anymore,” says Kerwin.

Though they are ecologically special places, Irish people have long considered bogs especially challenging spaces. “In the distant past, peat landscapes were both feared and respected as wilderness areas and often link to traditional culture, rituals, and worship. In modern times, peatlands have commonly been treated as wastelands that are of no use unless they are drained or excavated,” states an Irish Environmental Protection Agency report about bogland management.

But this perspective is slowly shifting. Since the 1980s, the Irish Peatland Conservation Council has called for the preservation of Irish bogs. The organization wants to protect unique habitats and ensure bogs continue to play their important role in Irish water systems for filtration and flood control. The council also hopes to keep the vast amounts of carbon in bogs from becoming harmful emissions. Globally, though peatlands cover only three percent of land, they store at least a third of the world’s soil carbon. That is more carbon than all plants combined, including carbon held in rainforests.

That carbon, which allows peat to function as a fuel, also makes it important in the climate change conversation. While waterlogged, Irish peatlands were a stable carbon store for thousands of years. When drained, they began releasing their carbon. An article published in the scientific journal Irish Geography in 2013 found that emissions from drained Irish peatlands are equal to annual carbon dioxide emissions from the entire transportation sector in Ireland. One of the article’s authors, Flo Renou-Wilson, a peatland scientist at University College Dublin, says though biodiversity increased at the Boora Bog Complex when a section was converted to Lough Boora Discovery Park, its peat soil is still releasing carbon dioxide because it hasn’t been fully re-wetted.

“If the water table remains low in the soil profile, drained peatlands are large emitters,” said Renou-Wilson.

New community-led projects have emerged in the last 15 years that offer a spark of hope for Irish peatlands. A new Irish organization called the Community Wetlands Forum formed in 2013 and supports projects that rehabilitate and care for their local bog. The forum’s membership includes 20 communities. There is also a government-funded Irish program called The Living Bog, that has singled out 12 raised bogs, the type formerly present at Lough Boora Discovery Park, in order to do intensive ecological restoration.

Lough Boora Discovery Park’s own rehabilitation was guided by Bord an Móna employee Tom Egan, one of the park’s creators. Egan arrived to the company 39 years ago, just as some of the mined bogs were depleted of harvestable fuel. He spent his career trying out different types of agriculture and forestry crops on their blank, black canvas, all of which struggled to thrive in low-nutrient peat soil.

“I came here in 1980 and quite literally came into a black landscape—quite ugly, industrially ravaged,” says Egan. A few years after he arrived, he noticed that one area called Turraun, which they had left alone since the mining on it ceased, was recolonizing with a wide diversity of wild plants and birds. That observation planted the seed for Lough Boora Discovery Park. After studying its potential as a recreational area, Bord na Móna established the park, which includes Turraun wetland in its boundaries. Today, the park hosts more than 270 plant species and more than 130 bird species, including overwintering migratory birds such as the Icelandic whooper swan and threatened birds such as the native grey partridge.

A few hundred feet down the sculpture trail from the rusting yellow train, the Japanese sculptor Naomi Seki posed a question with her creation. She planted a living birch tree next to a long wooden arm that stretches up to the sky. The explanation of her work on a plaque nearby states: “We finally learned to live and let live. When will the tree grow taller than the sculpture?” The sculpture was completed in 2002, and today, the tree’s height has reached beyond the wood.

“The most fascinating thing for me is what nature has done, how nature has transitioned that ugly landscape to what it is today,” says Egan.

This park in the heart of Ireland is a re-imagined post-industrial place that has been celebrated as one of Europe’s best sculpture parks. Egan says the evolution of Boora Bog Complex from an industrial landscape to a recreational one isn’t fully explained to park visitors. He hopes signage and other interpretive elements will be added to the park in the next five years to share that history. The bog’s journey continues.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook