How 17th-Century Women Replicated the Natural World on the Table

Inventive chefs made hedgehog pudding and creamy artificial snow.

“Observe when you walk abroad…and then your work will show the more naturally.” Recipe books don’t typically start this way. But for Hannah Woolley, cooking and science weren’t all that different.

When Woolley published The Ladies Directory: Choice Experiments and Curiosities of Preserving in 1661, she became the first woman in England to release a household manual. Women of all classes craved these insights, and the little book of recipes, remedies, and etiquette quickly became a huge hit. Woolley went on to publish four more books, and became the Martha Stewart of 17th-century England, making a living by selling her advice to the masses.

In addition to cakes, roasted meat, and jellies, a number of recipes in Woolley’s books particularly encouraged women to create food that mimicked animals or natural phenomena. In one recipe for “Hedgehog Pudding,” for instance, Woolley advised cooks to use almond slivers and raisins to craft a hedgehog’s spines and eyes, respectively, in the sweet treat.

These recipes, which Woolley dubbed “New Experiments,” coincided with experimental science taking off across England. They also connected women’s work in the kitchen with the more formal experiments taking place in the Royal Society. This association of physicians, natural philosophers (a 17th-century term for “scientist”), and experimenters—all male, all upper-class—was founded in 1660. In order to fulfill its mission of “Improv[ing] Natural Knowledge,” the Royal Society spent its time looking through microscopes and conducting experiments examining the nature of air, colors, and perception.

Women’s scientific thoughts, and the experiments they headed in their kitchens, were of little interest to the men of the Royal Society. When writer and natural philosopher Margaret Cavendish visited the Royal Society in 1667, for example, men dismissed her as silly, despite her interest in observing “several fine experiments…of colours, loadstones, microscopes, and of liquors among others,” as Samuel Pepys, a member of Parliament, wrote in his diary. Cavendish’s “dress [was] so antick, and her deportment so ordinary, that I do not like her at all,” he continued, “Nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing, but that she was full of admiration.”

But in 17th-century English kitchens, women like Cavendish and Woolley observed and recreated the natural world in inventive ways. Upper- and lower-class ladies alike crafted elaborate dishes comprised of sugar-paste, marzipan, or jelly to look and act like animals, plants, or natural phenomena. These dishes, often unveiled as centerpieces at banquets or presents for friends and family, displayed not only a lady’s culinary skill, but also how she studied nature. The more closely a woman understood nature, the more lifelike her edible kitchen creations would be.

Some of these recipes were ubiquitous, such as the one for snow cream, which appears in many 17th-century handwritten recipe books. Elizabeth Godfrey’s recipe draws on the reader’s observation of snow in nature to know when the cream is ready: “when you see it look light like snow take it off with a skimmer,” she notes. In order to get the texture of snow cream right, a woman would have had to carefully observe what snow both looked and felt like. In order to replicate nature on the table successfully, a woman had to have more than culinary chops: She also needed to have a dedication to studying the natural world.

Woolley’s recipes show that she had a particularly attentive eye. In The Queen-Like Closet, her most popular book, Woolley gave detailed instructions to craft a centerpiece called “A Rock in Sweet-Meats.” It was less a sweetmeat than it was a dazzling, wine-dispensing imitation seashore, complete with cookie rocks, sugar-paste snails and oysters, candies of all colors and, to top it off, a marzipan peacock with real feathers drinking from jelly “water.” How were women in the middle of England to know what such a seascape looked like, though? In the recipe, Woolley encouraged women to draw on their studies, replicating the variety “you know Nature doth afford” in food.

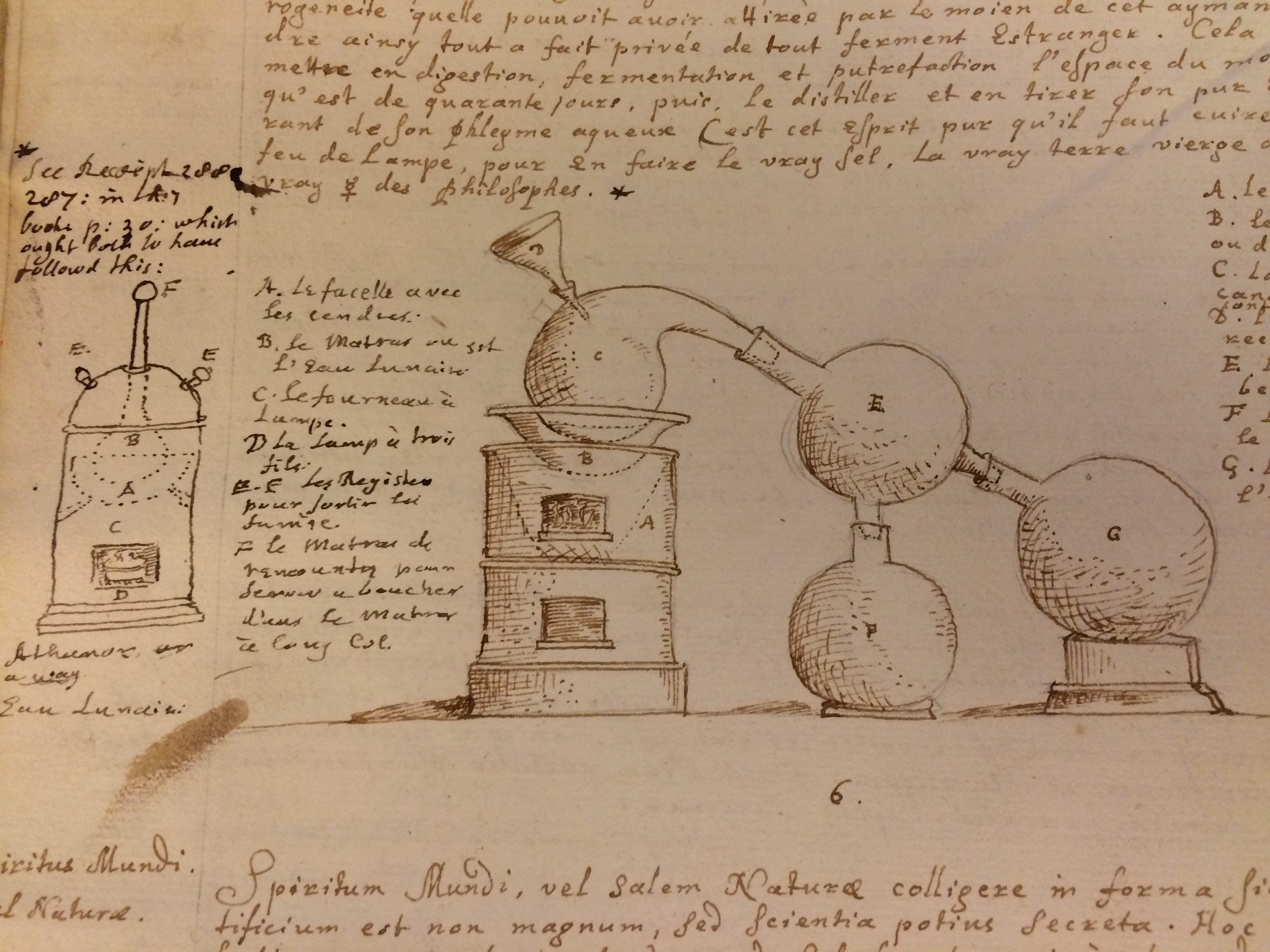

To bring these natural wonders to life, women scrappily distilled their own syrups and essences of fruits, flowers, or medicinal herbs, creating chemical reactions in household laboratories to transform natural products. Those who couldn’t afford the specialty molds necessary to hold their sugar-paste fruits, birds, animals, and plants creations made their own. This meant expertly carving the shape of these natural objects, in reverse, into wood or plaster.

More gruesome recreation methods, ones reminiscent of dissection and butchery, also brought nature to the dinner table. For instance, Robert May’s 1660 recipe book, The Accomplisht Cook, includes directions for theatrical banquet courses that featured live birds in a pie and a sugar-paste deer speared by an arrow in its side. When diners pulled out the arrow, wine would flow out of the deer “as blood running out of a wound.”

At first glance, the stag gave diners the pleasure of knowing what lay inside a deer. But it also revealed a woman’s keen ability to dissect nature. Wendy Wall, a professor of English who studies manuscript recipes, writes in Staging Domesticity: Household Work and English Identity in Early Modern Drama that butchering animals and healing bodies gave women an intimate knowledge of anatomy. By doing so, a woman “had her finger on the pulse of life and death.”

The practice of replicating natural life (and death) directly echoed emerging scientific discoveries of 17th-century England, which often required looking into or looking closely at objects. The microscope, invented around 1590, had recently captured the English imagination, and everyone wanted to see what nature looked like up close. In 1665, Robert Hooke published Micrographia, or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, the first book to illustrate insects, plants, and other small natural objects through a microscope. In Micrographia, Hooke showed that scientific knowledge comes through observing something closely and reproducing it through art. He also established the act of close observation as essential to science: Good scientists observed the world around them and replicated their findings to share with others.

While Hooke gained notoriety for publishing images of nature observed through a microscope, women observed it, too, in the ways available to them. In doing so, they also asked questions about the composition of the world: What is a snail or a strawberry made of if someone can create one from sugar paste? How does natural phenomena happen if sugar paste and food dye can be made to look natural, or if whipped cream can imitate snow?

Cavendish, one of the first people to insist on women’s role in scientific investigation, wrote in her 1667 scientific treatise, Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, that women “would prove good experimental philosophers, and inform the world how to make artificial snow, by their creams, or possets beaten into froth and ice…and many other the like figures, which resemble beasts, birds, vegetables, [and] minerals.”

She illustrated that women’s work was a central, if silent, part of the beginning of modern science. Women experimenting in their kitchens have been asking the same questions and doing the same work as their male counterparts, even as they were excluded from masculine spheres of professional science. Cavendish, Woolley, and countless other women employed similar methods and asking the same questions as their male counterparts in the Royal Society—the only difference being that women’s household science was ephemeral and edible.

By the turn of the 18th century, the practice of creating elaborate recreations of nature for the table had become a pastime for the nobility, whose large servant staff could do the painstaking work. But whether it was recreating a fruit or a rock, testing out recipe variations, or creating their own tools, the scores of women penning these recipes bear silent and revolutionary witness to the storied tradition of kitchen experimentation.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook