About

In 1864, the famous French world traveler Louis Rousselet described "[a] vast sheet of water, covered with lotuses in flower, amid which thousands of aquatic birds are sporting" at the shores of which bathers washed, surrounded by jungle greenery. He was not describing a lakeside scene or one of India's famous riverside ghats, but an ancient well, as big as a large pond.

In the northern Indian states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, the problem of water is a profound one. At the edge of the Thar desert, the area sees torrential seasonal monsoons, and then watches the water disappear almost immediately. With summers routinely over 100 degrees, and silty soil that would not hold water in ponds, a practical solution was needed for locals and travelers along the local trade routes.

In the first century, the slippery shores of the major rivers were tamed by the construction of ghats, long, shallow sets of stairs and landings. The same approach was applied to the construction of a new kind of well.

The earliest stepwells most likely date to about 550, but the most famous were built in medieval times. It is estimated that over 3,000 stepwells were built in the two northern states. Although many have fallen into disrepair, were silted in at some point in antiquity, or were filled in with trash in the modern era, hundreds of wells still exist. In New Delhi alone, there are more than 30.

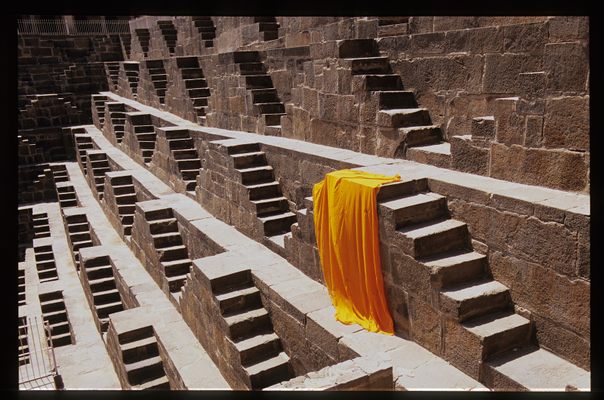

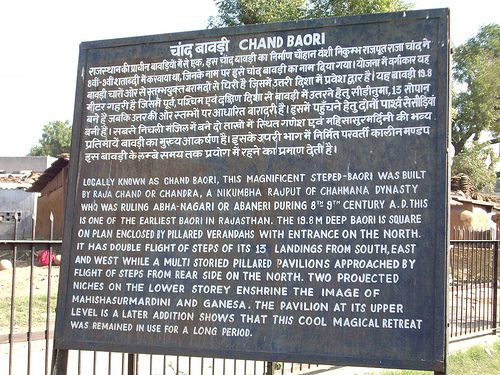

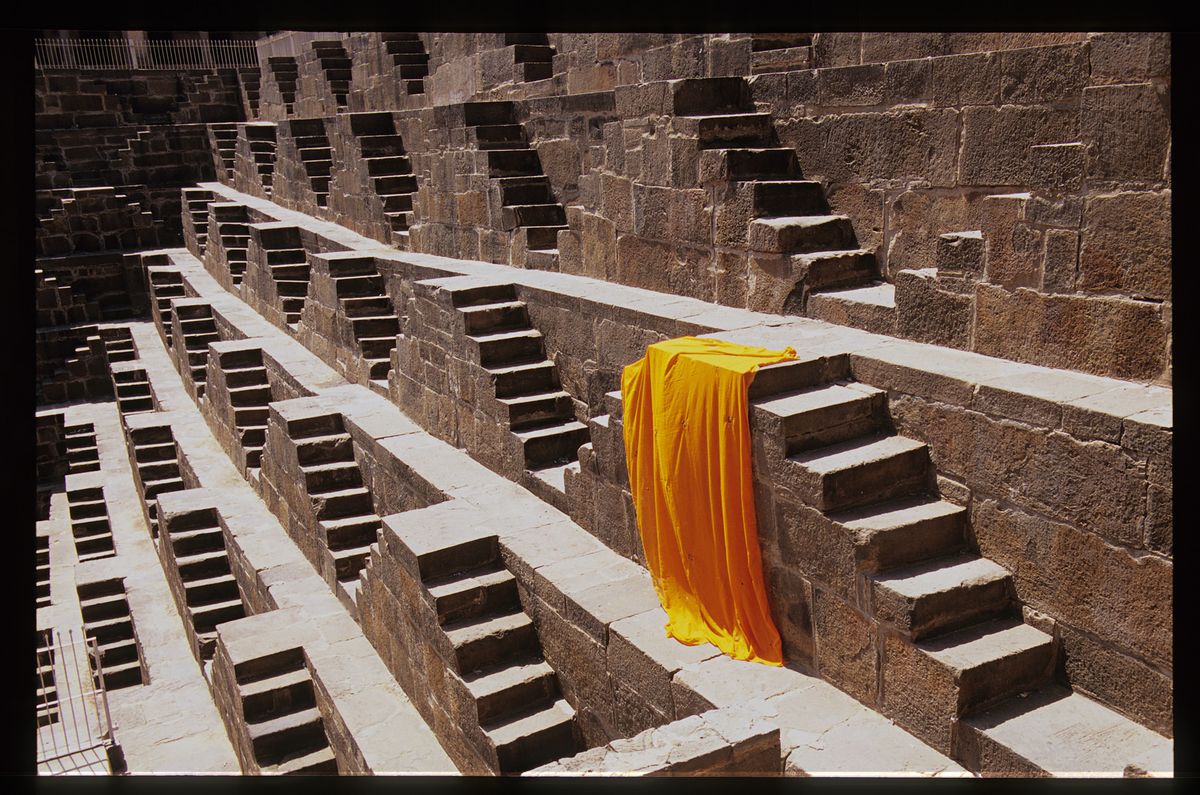

Chand Baori in Abhaneri, near Jaipur, Rajasthan, is among the largest, if not the largest, of the stepwells. It is also perhaps the most visually spectacular: Chand Baori is a deep four-sided structure with an immense temple on one face. Some 3,500 Escher-esqe terraced steps march down the other three sides 13 stories to a depth of 100 feet. The construction dates to the 10th century, and is dedicated to Harshat Mata, goddess of joy and happiness.

Water plays a special part in Hindu cosmology, as a boundary between heaven and earth known as tirtha. As manmade tirtha, the stepwells became not only sources of drinking water, but cool sanctuaries for bathing, prayer, and meditation. The wells are called by many names. In Hindi they are baori, baoli, baudi, bawdi, or bavadi. In Gujarati, spoken in Gujarat, they are commonly called vav.

The architecture of the wells varies by type and by location, and when they were built. Two common types are a step pond, with a large open top and graduated sides meeting at a relatively shallow depth. The stepwell type usually incorporates a narrow shaft, protected from direct sunlight by a full or partial roof, ending in a deeper, rounded well-end. Temples and resting areas with beautiful carvings are built into many of the wells. In their prime, many of them were painted in bright colors of lime-based paint, and now traces of ancient colors cling to dark corners.

The use and conditions of stepwells began to decline in the years of the British Raj, who were horrified by the unsanitary conditions of these drinking water bathing spots. They began to install pumps and pipes, and eventually outlawed the use of stepwells in some places.

The remaining stepwells are in varying states of preservation, and some have gone dry. Local kids seem to find the ones with water to be terrific diving spots, which seems insanely hazardous.

Related Tags

Delhi and Rajasthan: Colors of India

Discover Colorful Rajasthan: From Delhi to Jaipur and Beyond.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

October 15, 2009

Sources

- http://www.jaipur.org.uk/excursions/abhaneri.html

- Cross section diagram of a stepwell

- http://www.orientalarchitecture.com/india/ahmedabad/adalaj.php

- http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/mp/2002/11/18/stories/2002111800900200.htm

- http://www.dancewithshadows.com/vavs_stepwell_gujarat.asp

- http://www.gonomad.com/traveltalesfromindia/2009/10/attractions-at-bundi-raniji-ki-baori.html

- http://smoont.com/the-deepest-step-well-in-the-world/