Boadicea and Her Daughters

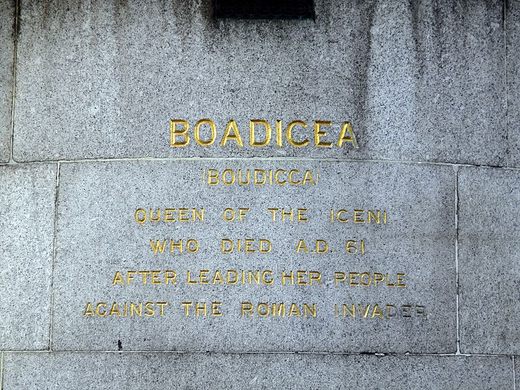

A statue of the legendary Celtic warrior queen who fought the Roman invaders stands in one of the cities she once destroyed.

On the western end of Westminster Bridge stands a bronze sculpture of a horse-drawn chariot driven by three women. The crowned leader of this trio holds a spear aloft in one hand, her other hand raised as if in challenge, her gaze fearless and her facial expression suggesting a grim determination.

This Victorian-era statue sculpted by artist Thomas Thornycroft represents Boadicea (also spelled Boudica or Boudicca, though Boadicea was most common when the statue was created), the warlike queen of the Celtic Iceni tribe and her daughters, who are legendary and tragic figures in ancient British history, art, and folklore.

The Iceni were a tribe that inhabited a territory comprised of present-day Suffolk, Norfolk, and Cambridgeshire. During the first 50 years of the Roman occupation of Britain, relations between the colonial forces and the indigenous Iceni were generally peaceful, as after a few battles the Romans allowed the tribe to be an independent ally.

During this period, the Iceni were led by a king named Prasutagus who sought to continue this independence by naming the Roman emperor Nero as co-heir to his kingdom with his two daughters. However, upon his death in the year 61, these plans went spectacularly wrong and subsequent events sparked one of the most infamous wars on British soil.

The psychopathic Nero rejected the terms of Prasutagus’ will, and instead gave orders to seize the kingdom by force and violate and punish Prasutagus’ next of kin. Consequently, a legion of Roman soldiers marched into the territory and seized Boadicea—Prasutagus’ widow and the queen of the Iceni— and her teenage daughters.

Boadicea was beaten and tortured, and her daughters endured extreme sexual violence. The family’s land, property, and wealth was then confiscated and they were cast out into exile. Because of this appalling treatment, the Iceni tribe rose up in rage and rallied around Boadicea, who quite understandably sought vengeance.

Word spread across Britain, and soon other Celtic tribes with historic grievances against Rome joined the uprising. It’s said the insurgent army Boadicea assembled eventually numbered over 100,000 warriors. The troops first attacked the city of Colchester and burned it to the ground, slaughtering the resident Romans and demolishing the temples. A Roman legion sent to rescue the city were butchered, and the commander and a handful of survivors only narrowly escaped with their lives by fleeing speedily on war chariots.

The warriors then attacked Londinium (today known as London), which the Roman population had already largely evacuated. The rebels killed and tortured any remaining inhabitants, destroyed their shrines, and burned their buildings to the ground. The town of St. Albans followed, and its entire population was put to the sword. An estimated 70,000 to 80,000 people were killed by the rebels during the attacks on the three cities, and the news of the slaughter spread far and wide across the Roman empire.

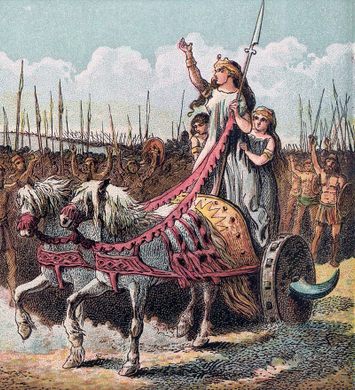

The Roman commander Suetonius responded by launching a re-invasion of Britain and led a legion of elite soldiers to destroy Boadicea and her army. The Celtic rebels were eventually routed in the West Midlands, where they were caught by surprise. According to popular lore, Boadicea led her army into a final stand against the enemy driving a war chariot, her daughters accompanying her. After a short and fierce battle, the rebels were defeated. The last reports of Boadicea following her defeat suggest she died by suicide by imbibing a potion of yew tree poison. The fate of her daughters was not recorded, but it is likely that they died in battle.

However, the fierce queen of the Iceni has never quite been forgotten, and she still looms large in the collective imagination of the British as a romantic and tragic figure who led her country against invaders (the mass killing of Romans is often glossed over). As such, her story has been revived throughout the ages in everything from Elizabethan and Georgian poems and plays, to Victorian art to modern-day television drama series.

Know Before You Go

You'll see the statue on the western end of Westminister bridge. You can walk by it at any time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook