George Parkman House

The former home of a Boston physician whose murder led to a revolution in forensic science.

Located at the edge of Beacon Hill and directly across from Boston Common, the George Parkman House looks almost identical to many other buildings in the area. There isn’t even a plaque indicating its historical association, but this unassuming home has a dark history. It once belonged to the victim in one of the most sensationalized murder trials of the 19th century, which also revolutionized the field of forensic science.

George Parkman was a Boston Brahmin and a member of one of the richest families in the city. Parkman’s poor health in his youth led him to pursue a career in medicine. He enrolled in Harvard at age 15, traveled across Europe, was a surgeon during the War of 1812, and played a key role in reforming various psychiatric institutions across the state.

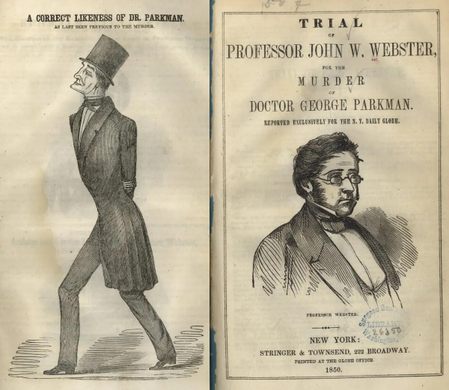

Parkman found great success and wealth in his life and was a well-known figure within the city. He was tall, lean, had a distinct protruding chin, and walked the streets daily wearing a top hat. His net worth was around $500,000 (the equivalent of nearly $10 million today), and he was quite generous with his wealth. But all of this came to a sudden and abrupt end in the autumn of 1849.

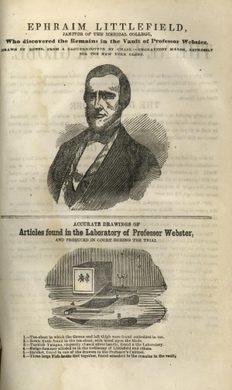

On November 23, Parkman left his house to go on his daily walk and collect debts from the city’s various residents. Earlier that day, John White Webster, a professor at Harvard Medical College and one of Parkman’s debtors, suggested they meet at the college to discuss his debt. Parkman was last seen entering the college around 1:45 p.m. Later in the afternoon, the campus janitor Ephraim Littlefield found Webster’s lab locked and heard water running inside. Webster attended a party later in the evening but Parkman was nowhere to be found.

The next day Parkman’s family began making inquiries with the police and Littlefield noticed Webster holding a bundle of wood and behaving strangely. Webster claimed he paid Parkman the money he owed but had not seen him since. A $3,000 reward was offered for his safe return, and speculation ran wild within the city. Some thought he was kidnapped, while others guessed that he had simply left the city.

As the investigation intensified, Littlefield began feeling nervous—he had been one of the last people to see Parkman alive and was concerned people might link him to the disappearance. On November 28, the custodian observed the furnace in Webster’s lab burning so intensely that the wall on the other side was hot to the touch. He noticed that the kindling barrels were empty despite being recently filled and there was a strange, acrid odor in the air.

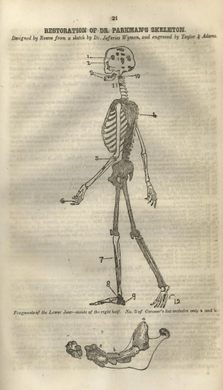

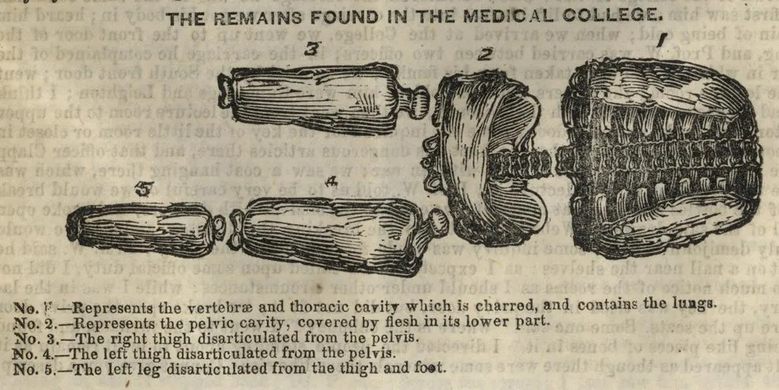

The next day Littlefield returned, knowing the lab would be empty for the Thanksgiving holiday. With tools in hand and his wife standing guard, he began chiseling away at the wall under Webster’s private privy. Inside the hole he had created, Littlefield discovered charred, dismembered, and partial skeletal remains. He immediately notified the authorities and Webster was arrested for murder. The professor initially denied any wrongdoing, but upon being told of the graphic nature of Littlefield’s discovery, broke down and confessed to the crime.

The arrest and crime made headlines. Further investigation of Webster’s lab turned up a dismembered torso. Definitive identification was made when Nathan Cooley Keep, Parkman’s dentist, identified the teeth found in the furnace. Examining a victim’s teeth would become the primary way police used to identify skeletal remains until the introduction of DNA in the 1980s.

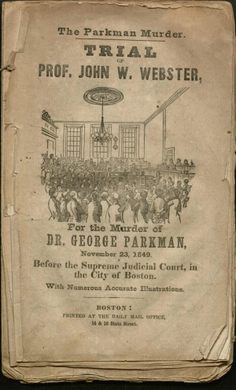

The murder trial for Webster began in January of the following year, with much sensation from the press and media. After two months, the jury delivered a guilty verdict. This marked the first time that forensic dentistry was used to convict a murderer. Judge Lemuel Shaw sentenced Webster to death by hanging. Webster was taken to Leverett Street Jail in Boston and was executed on August 30, 1850.

Although it may appear rather ordinary, the George Parkman house has a direct connection to one of the most gruesome murder trials of the 19th century in the United States. The case was a landmark development in criminal forensic science which has since provided evidence helping solve many crimes across the world for over a century and continues to play a significant role.

Know Before You Go

There is another George Parkman house nearby located on 33 Beacon Street which belonged to his son George Parkman Jr. The two sometimes get mixed up.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook