Weaver Historical Dental Museum

This museum boasts a bucket of teeth and tells the tale of a 20th-century dental circus.

Showgirls, singing, and dancing. A band with blasting bugles. A dental chair poised, at the ready, in the bed of a horse-drawn wagon. And there at the center of it all is Painless Parker, dressed to the nines in his spotless white frock-coat and trademark gray brushed-beaver top hat. Around his neck is a long necklace of teeth, 357 of them to be exact, all pulled, Parker claimed, on one day right from that very chair in his traveling office.

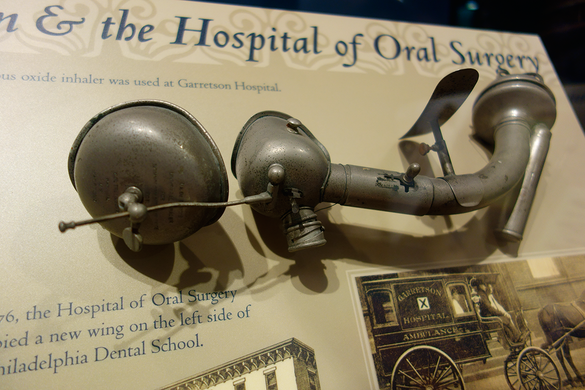

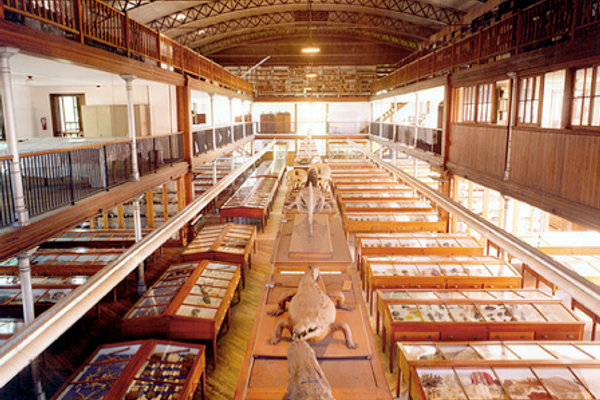

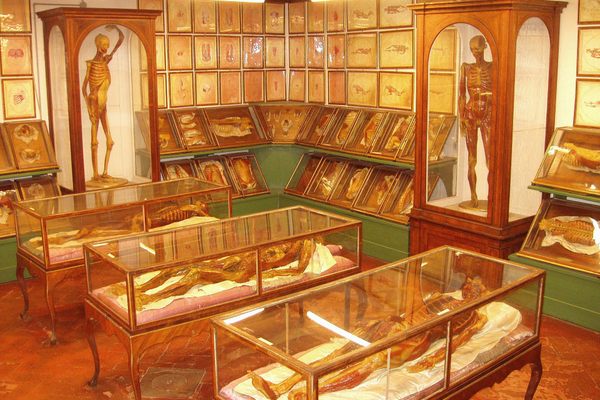

The small but delightful Historical Dental Museum at the Temple University School of Dentistry in Philadelphia has a lovely collection of antique dental student teaching aids. Some of the best items—like a delicate set of blue wax teeth—were created by students as part of their graduation requirements and then left behind. Every student was required to carve a set of teeth like this to demonstrate intimate knowledge of the anatomy of each tooth. The practice ended in the 1970s, but according to a plaque at the museum, the practice was recently reintroduced.

The collection is incredibly charming, and the sense that each item was a practical tool that was actually used at one point in history gives each of the tiny bone-handled instrument a feeling of purposefulness.

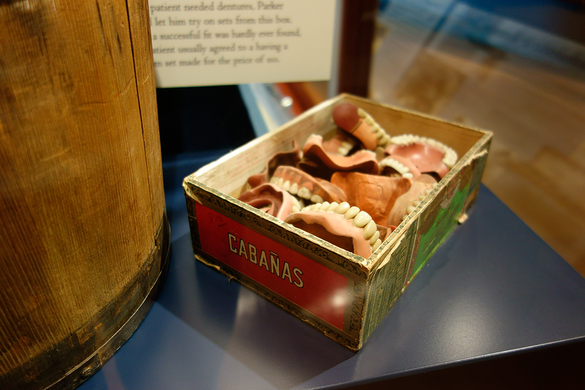

But there’s more to the museum than the story of a famous early dental program: A plaque reading “PAINLESS PARKER” stands next to a long strand of teeth. Just below that, a large wooden bucket is filled to the brim with dirty old teeth. These items have nothing to do with Temple, save that the legendary dentist who owned them, Edgar Randolf Rudolf Parker, graduated from the Temple School of Dentistry, along with just three other students, in 1892.

Upon graduating, Edgar R. R. Parker moved back to his hometown in Canada to open his own dental practice. Parker was disappointed to discover that there just wasn’t any business. Parker knew he was a good dentist and couldn’t stand the idea that his practice might never take off, so he decided to take matters into his own hands: He would become the P.T. Barnum of dentistry.

Working in the 1890s during the height of “humbugs,” dime museums, and rational amusements, Parker did what any natural-born showman would do. He took a cue from the best and hired one of P.T. Barnum’s ex-managers to help him take his practice on the road. From his horse-drawn office, amid his showgirls and buglers, Parker promised that he would painlessly extract a rotten tooth for 50 cents. And if the extraction wasn’t painless, he would give the customer $5.00, the equivalent of roughly $115 today. Parker’s band actually served a three-way purpose. First, it drew a crowd. Second, it distracted the patient whose tooth was being pulled (along with a healthy cup of whiskey or an aqueous solution of cocaine he called “hydrocaine”). And, third, it drowned out any possible moans of pain emitted from the patient.

To help advertise his business, Parker place a bucket full of teeth he had personally pulled by his feet as he lectured to the crowds on the importance of dental hygiene. Naturally, like most showman-practitioners, his shameless advertising was looked down upon in the medical community. Around 1915, Parker was ordered to stop advertising himself as “Painless Parker,” as this was considered potential false advertising. Unperturbed, Parker skirted the issue by legally changing his first name to Painless. No one could tell him not to advertise under his own name.

Upon his death in 1952, Time magazine stated that Parker’s “ballyhooing techniques and easy professional ethics boomed his practice but outraged his colleagues.”

Though Painless Parker’s blatant advertising pushed the boundaries of respectability and even legality, Parker believed in bringing oral education and affordable services to everyone, bringing the dentist to them rather than bringing them to the dentist. Moreover, he believed in cheap and—at least, usually—painless tooth extractions. As the plaque at the museum states, “Much of what he championed—patient advocacy, increased access to dental care and advertising—has come to pass in the US.”

Know Before You Go

Inside the Temple University School of Dentistry, the museum is just outside of the elevator on the third floor of the building.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook