About

Due to its role in navigational matters, the importance of time to sailors in the 17th century cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, their handle on this all-important matter while at sea was tenuous at best.

It was only logical, therefore, that the British Empire saw fit to hold a contest, whereupon they would bestow a massive prize to the first clockmaker who could deliver a timepiece capable of functioning on the open ocean. Try as they might, all the biggest names in horology proceeded to fail miserably at this challenge for decades on end. "The longitude problem" was thought to be unsolvable.

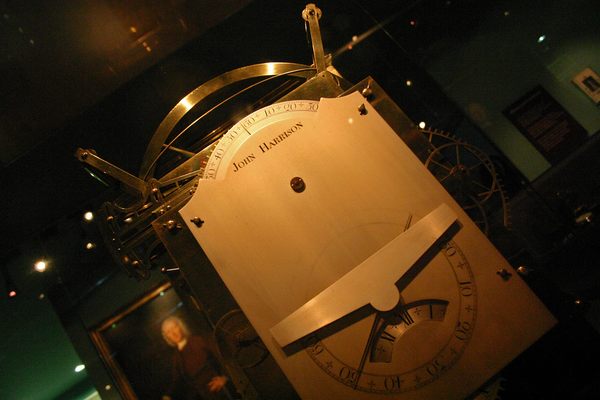

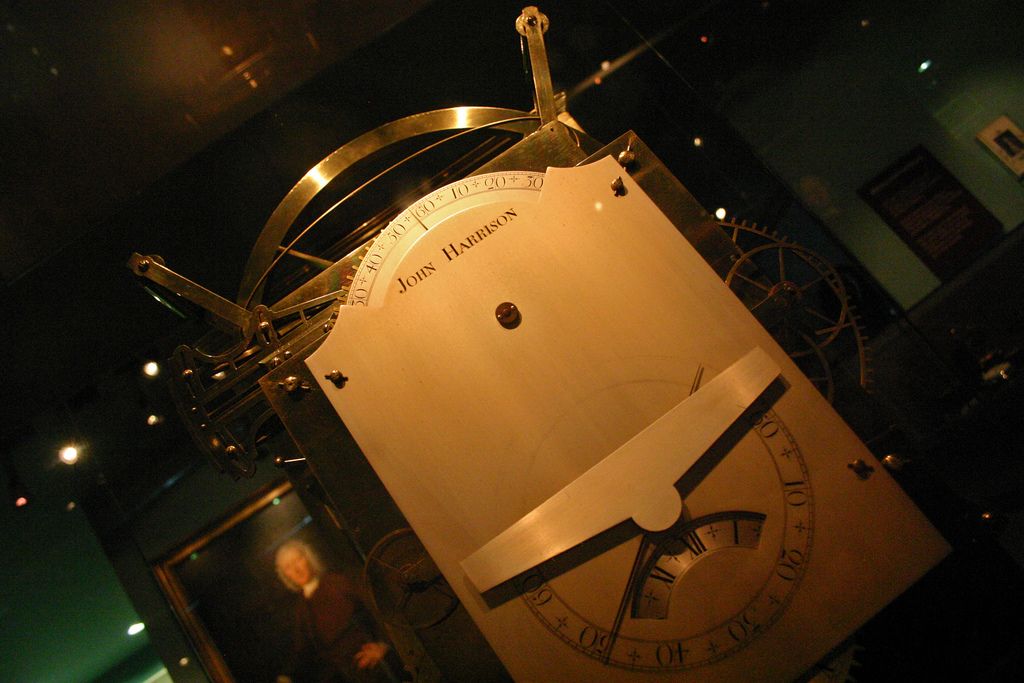

Then, out of nowhere, the equivalent of a shade-tree mechanic strode in with a prototype of a marine timepiece that decimated any example yet presented to the Commissioners of Longitude. His name was John Harrison.

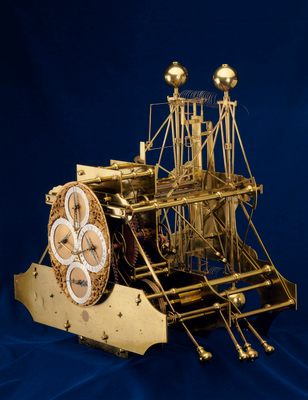

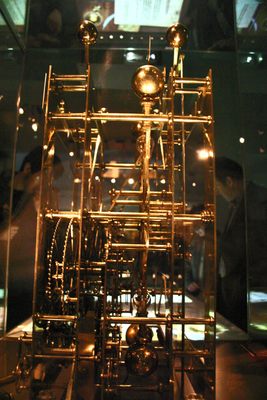

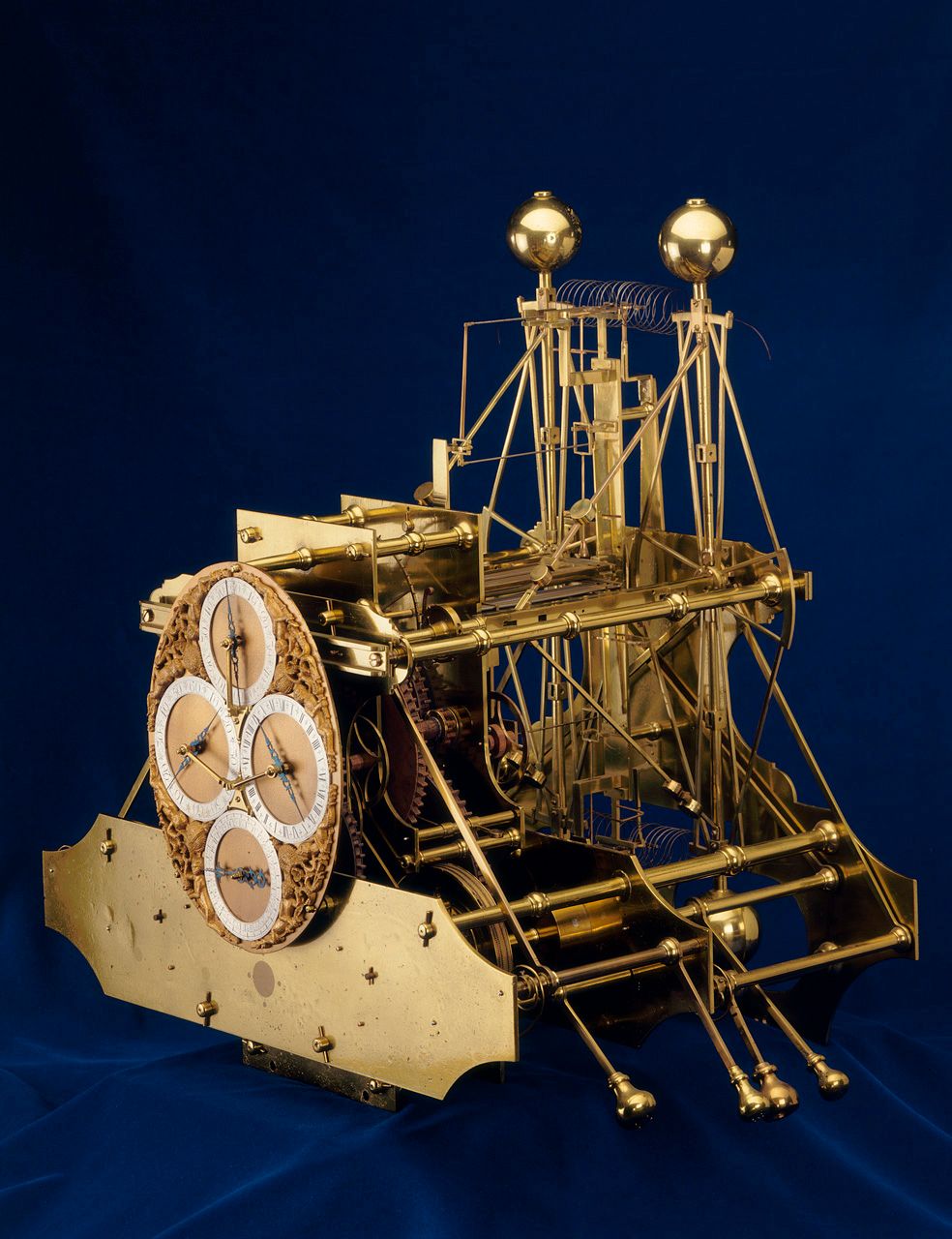

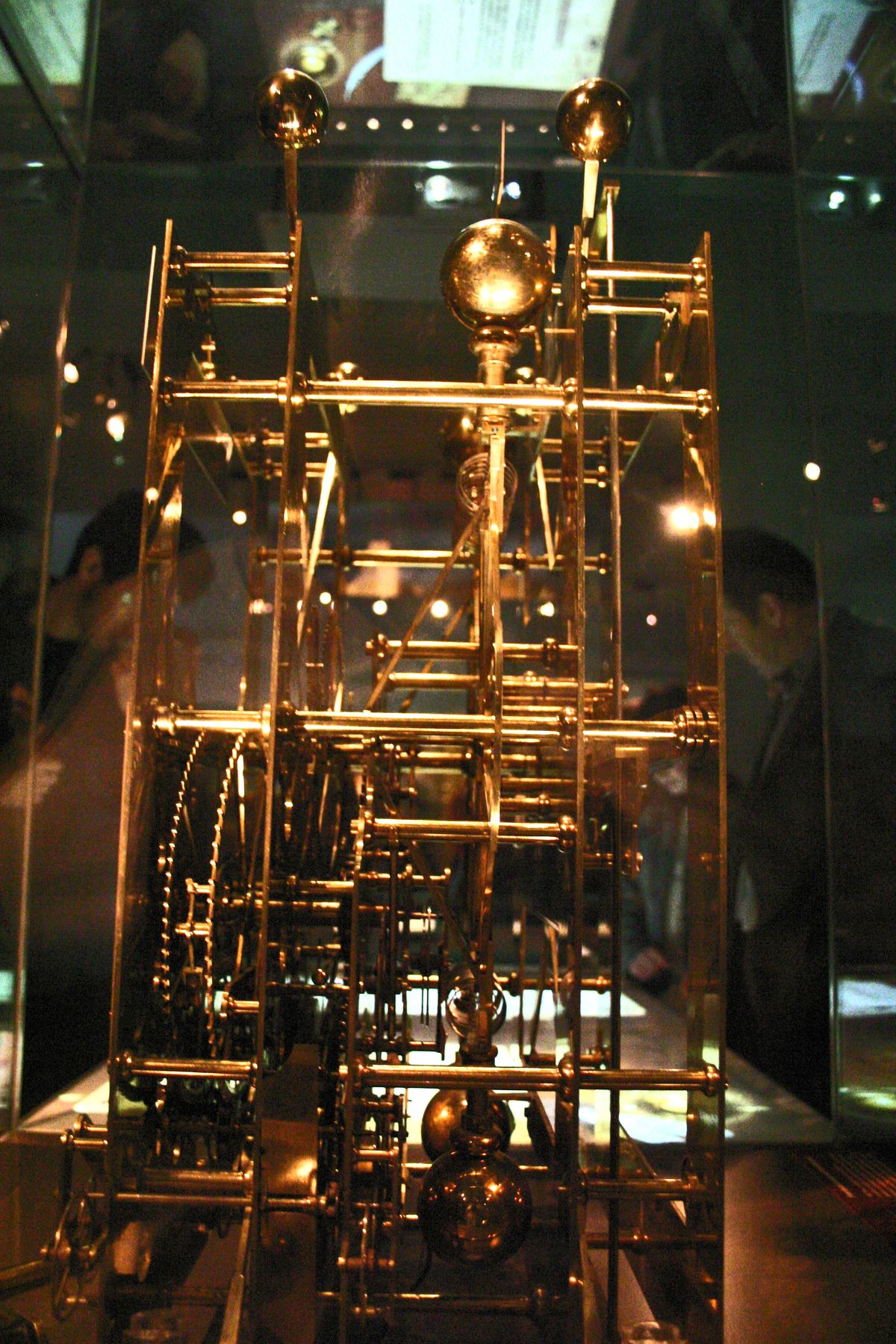

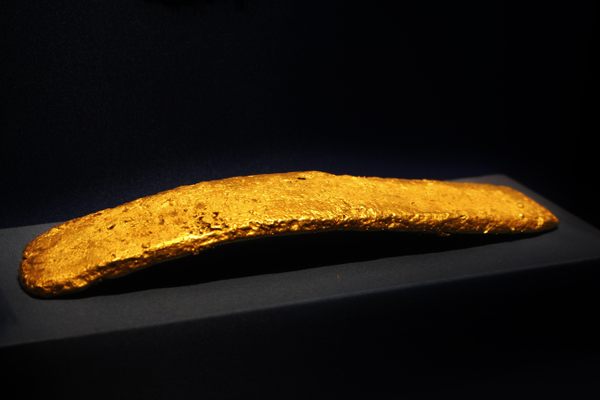

Constructed between 1728 and 1735, the self-educated carpenter and clockmaker developed his revolutionary H1 prototype based on a series of wooden clocks dependent upon counterbalanced springs rather than gravity. The device was given a trial at sea in 1736, during which test it performed well enough that Harrison was able to earn a stipend to work on his next prototype, the H2, from the Board of Longitude. A third prototype would follow before Harrison entirely abandoned the clock body style in favor of the "sea watch" design seen in his later H4 and H5 models.

Building these five timepieces consumed a total of 46 years of Harrison's life. Though his creations were precise beyond anyone's wildest dreams (considering the task itself was considered impossible before he arrived on the scene), the task of claiming the aforementioned prize proved to be more insurmountable than building the clocks.

Given that Harrison wasn't a member of the ultra-exclusive Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, his timepieces would repeatedly pass the tests outlined by the Board of Longitude only to have individuals invalidate his results through personal anecdotes. Harrison was, effectively, shut out from his reward for designing the functioning H4 and H5 even as its technology was being handed off to other clockmakers.

Ultimately it took an act of Parliament and a personal threat of intervention from King George III before the Board of Longitude remitted anything to Harrison for his achievements. Despite everything, the full prize money was never distributed to anyone, including Harrison.

At the time of Harrison's death in 1776, James Cook had just returned from circumnavigating the globe using the technology developed by Harrison. It is unclear whether the watchmaker was aware of his role in this triumph before he passed away.

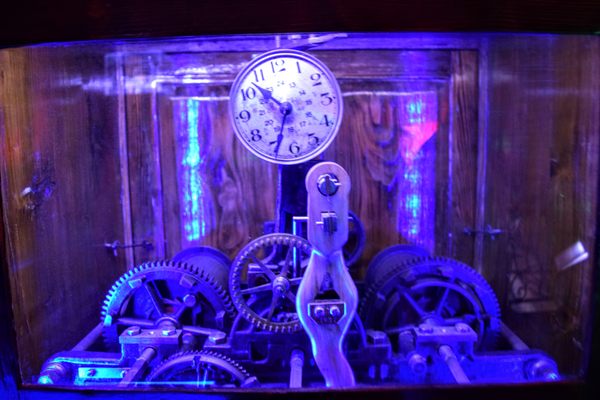

Harrison's original H1-H4 prototypes are on display at Flamsteed House at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, where they are lauded for having revolutionized seafaring the world over. The first three continue to tick away in full view, 250 years after their conception. Only the H4, is kept in a stopped state, for it alone requires oil to lubricate its gears, meaning its delicate gears would degrade over time were it left running.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The museum is only a short walk from the Cutty Sark DLR, local bus stops, Greenwich Pier and Greenwich and Maze Hill stations.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

August 17, 2015

Sources

- http://www.rmg.co.uk/explore/astronomy-and-time/time-facts/harrison

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Harrison#The_first_three_marine_timekeepers

- http://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/apr/19/clockmaker-john-harrison-vindicated-250-years-absurd-claims

- http://www.rmg.co.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/on-display/time-and-longitude