About

In 2008 an eight year old boy named Miguel was kicking a ball with his friends alongside an industrial waterway in northwestern Mexico. The ball rolled into the water, and Miguel walked to the riverside to pick it up. When he reached down, he accidentally fell into the river. After grabbing the ball, he immediately pulled himself out. Later that night, Miguel began to vomit. He was sent to the nearby hospital, where he fell into a coma. 18 days later, Miguel died from arsenic poisoning.

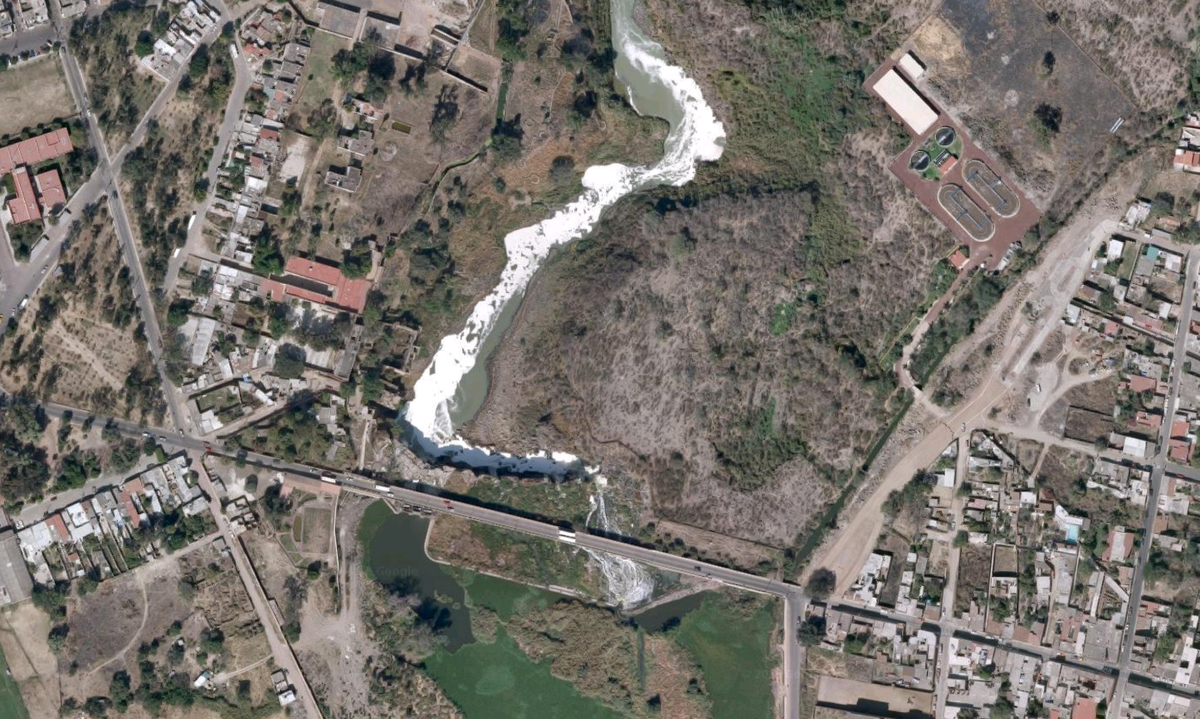

Miguel had fallen into the Rio Lerma (Chignahuapan) in El Salto, Mexico, one of the most polluted rivers in Mexico. His brief contact with the water was enough to kill him.

El Salto is a former European colony that was declared an industrial area in 1964 by the Mexican government. Dozens of industries have since located themselves in El Salto, including Hershey’s, Honda, Pepsi, Huntsman (a chemical production company), and producers of plastic, asphalt, heavy metals, chemicals, textiles, petroleum, electronics, herbicides, and many other toxic substances.

Enrique Enciso Rivera, a resident of El Salto told Atlas Obscura, “to El Salto [industrialization] seemed like ‘progress’ without knowing that it would set up the foundations for our own demise. It killed the longest river in Mexico, the Chignahuapan (the old word of the Nahuas that means ‘the power of nine rivers’).”

Rivera isn't exaggerating: the industries killed the river. As the companies moved in and discharged untreated waste, including lead, mercury, arsenic, phosphorus, and cyanide, directly into the river it became covered in a white foam and the fish died off in mass numbers. In total, more than 1000 different chemicals are deposited into the river each year.

It wasn't just the wildlife that was effected. The town’s health began to suffer. Respiratory disease and kidney failure became two of the largest causes of death in the town. Supplies of food and water were poisoned with arsenic and mercury. Consequently, the cancer rate in El Salto grew to be nine times Mexico’s average. One El Salto woman lost three of her children, a daughter in law, and a cousin to cancer. One girl's neck became rough and pitch-black, like the skin of a gorilla, from the pollution. When it looked like it couldn’t get any worse, it did.

Signed in 1993, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) resulted in fewer environmental regulations for transnational corporations operating in Mexico. After NAFTA was signed, environmental inspections on businesses in Mexico dropped by 45%. As a result, the environment became increasingly worse–so bad that modern-day Mexico spends over 10% of its GDP cleaning up environmental damage.

The impact on El Salto was devastating. The number of industries in the town skyrocketed to 300, the majority being American-run maquiladoras. As of now, 80% of the companies in El Salto release their toxic discharge into the water at a rate of 215 gallons per second, yet not a single fine has been cast due to lack of regulation. Rivera says that NAFTA sparked “an aggressive process of reindustrialization, with maquiladoras, and non-Mexican key industries...this worsened the amount of environmental damage, in our case the very devastating hydrological damage. It dug the tomb for traditional agriculture; the old people went to the businesses and the young people deserted the fields.”

In short, says Enrique Enciso Rivera, “El Salto since its foundation is a very local example of what not to do in the world.”

There may be some small good news for El Salto. A group called Un Salto de Vida, whose members include Enrique Rivera, is fighting the contamination via protests and activism. The cost of fully cleaning up the mess is no laughing matter - $643 million - and regulating the actions of El Salto’s transnational corporations must be an integral part of the solution. Perhaps, with the support of the international community, the people of El Salto can eventually have their river back.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Un Salto de Vida, the NGO based between the communities of El Salto and Juanacatlán in the state of Jalisco, and the cleanup of Río Lerma are the subject of a 2016 documentary by filmmaker Eugenio Polgovsky called "Resurrección".

Yucatan Family Adventure: Meteors, Pyramids & Maya Legends

Explore Maya temples and learn about the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

May 24, 2016