About

Until the 19th century, the sudden annual disappearance of white storks each fall had been a profound mystery to European bird-watchers.

Aristotle thought the storks went into hibernation with the other disappearing avian species, perhaps at the bottom of the sea. According to some fanciful accounts, “flocks of swallows were allegedly seen congregating in marshes until their accumulated weight bent the reeds into the water, submerging the birds, which apparently then settled down for a long winter’s nap.” A 1703 pamphlet titled “An Essay toward the Probable Solution of this Question: Whence come the Stork and the Turtledove, the Crane, and the Swallow, when they Know and Observe the Appointed Time of their Coming,” argued that the disappearing birds flew to the moon for the winter.

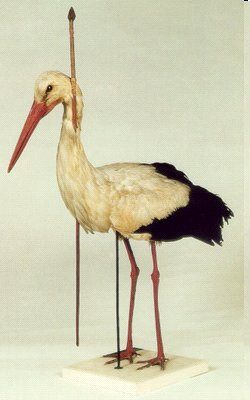

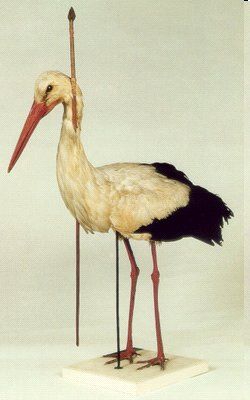

On May 21, 1822, a stunning piece of evidence came to light, which suggested a less extra-terrestrial, if no less wondrous, solution to the quandary of the disappearing birds. A white stork, shot on the Bothmer Estate near Mecklenburg, was discovered with an 80 cm long Central African spear embedded in its neck. The stork had flown the entire migratory journey from its equatorial wintering grounds in this impaled state. The Arrow-Stork, or Pfeilstorch, can now be found, stuffed, in the Zoological Collection of the University of Rostock. It is not alone. Since 1822, some 25 separate cases of pfeilstorches have been recorded.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

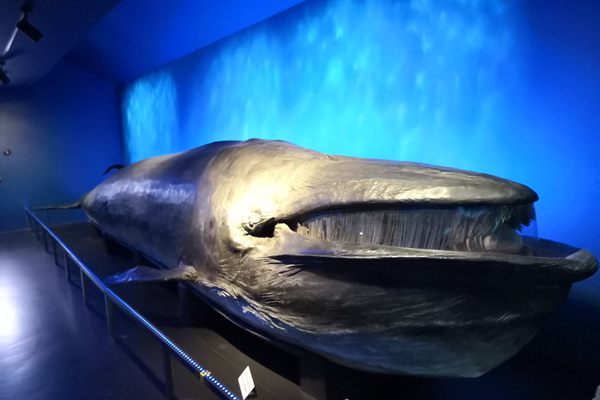

The museum is also home to nine glass Blaschka models of invertebrate marine life.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

March 20, 2009