10 Stunning Scenes of Mammal Migrations

Mule deer wading along the Red Desert-Hoback migratory route in western Wyoming (Photo: Joe Riis)

Mule deer wading along the Red Desert-Hoback migratory route in western Wyoming (Photo: Joe Riis)

Long-distance migrations are a deep-rooted impulse for many hoofed mammals around the world, and a rare spectacle for any witnesses who happen to be driving by. Whether it’s a black sheet of wildebeest emerging onto a plain or a band of pronghorn filing through rimrock foothills, the beasts that still survive by ancient pathways map profound geographies in their annual circuits.

Spurred to move by the green of a far-off pasture, the promise of water in a desiccated season, or the call of millennia-old breeding grounds, the migratory herds negotiate slews of physical obstacles: rivers, mountain ramparts, storms, and scanty food and water. These dramatic rounds are a reminder that landscapes are not just stitched together in stone and dirt, but also by the movements of their native creatures. Below, 10 of the greatest overland migrations.

Caribou Migrations of the Far North

Some of the Western Arctic caribou along the Noatak River in northern Alaska (Photo: National Park Service)

Some of the Western Arctic caribou along the Noatak River in northern Alaska (Photo: National Park Service)

Caribou—those big-eyed, big-hoofed deer of the high latitudes—carry out the greatest yearly journeys of any terrestrial mammal. In northern Eurasia and North America, barren-ground caribou and some populations of woodland caribou make these annual pilgrimages. Wintering grounds are often in boreal woods offering meager but critical lichen fodder; summer range tends to be on open tundra, where the cows synchronize births to overwhelm predators. Though territories may be separated by “only” a few hundred miles, the zigzagging routes taken by the animals as they graze, avoid mosquito clouds and wolf packs, scout the most auspicious river fords, and otherwise respond to conditions on the ground may exceed 3,000 miles.

The Western Arctic caribou herd of northwestern Alaska—historically one of the largest bands on Earth, along with the George River herd of northern Labrador and Quebec and the Taimyr Peninsula herd of northern Siberia—annually slogs across some 140,000 square miles, wintering on and around the eastern Seward Peninsula and calving on the tundra north of the Brooks Range. Among the singular thoroughfares on their trek is the Great Kobuk Sand Dunes, which looks like a tract of the Sahara misplaced between the Kobuk River and the Waring Mountains. Native Alaskans have hunted the caribou at their traditional crossing point of the Kobuk, Onion Portage, for 9,000 years running. (Both the dunes and Onion Portage are located in Kobuk Valley National Park.)

Caribou of the Western Arctic herd swimming the Kobuk River along the Brooks Range (Photo: National Park Service)

Caribou of the Western Arctic herd swimming the Kobuk River along the Brooks Range (Photo: National Park Service)

From Siberia to Quebec, pipelines, roads, and other manmade infrastructure increasingly complicate the age-old caribou routes. The Porcupine herd, which calves on the coastal plain of Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, has been at the center of the long-running debate over oil-drilling in that sanctuary.

The Serengeti-Mara Migration

Wildebeest crossing Kenya’s Mara River (Photo: Christopher Michel/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Wildebeest crossing Kenya’s Mara River (Photo: Christopher Michel/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

There’s likely no more famous overland migration on Earth than that of the 9,650-square-mile Serengeti-Mara ecosystem. Nowhere do so many big mammals mass together in long-distance movement. Blue wildebeest, 1.3 million strong, anchor this mighty journey, accompanied by some 600,000 plains zebras and Thompson’s gazelles.

A great clockwise round defines the migration. With the onset of the “short rains” of November, the wildebeest herds move southeast into the shortgrass plains of the southeastern Serengeti; they remain here during the “long rains” that usually prevail from March to May, calving and grazing on forage enriched by volcanic deposits from the Crater Highlands just east. As the rains diminish, the herds—accompanied now by young calves—head northwest toward their dry-season range in the grass woodlands of far northern Serengeti National Park and Kenya’s adjoining Masai Mara National Reserve, often spending time along the way in the hilly woods and grasslands of the Serengeti’s Western Corridor. Resident lions, spotted hyenas, and other big carnivores everywhere cull the multitudes; intense river crossings, including of the crocodile-filled Mara River in the north, are just as fearsome.

The interspecies herds of the Serengeti-Mara migration (Photo: David Dennis/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

The interspecies herds of the Serengeti-Mara migration (Photo: David Dennis/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

The Serengeti-Mara migration is an intricate choreography, involving what ecologists call a “grazing succession”: Zebras munch tall, rough grass ahead of the wildebeest, which then clip the shorter stalks; enriched by this cropping and all the ungulate droppings, the grass then sends up fresher, nutrient-rich shoots favored by Thompson’s gazelles. Surprisingly, the impetus for the 600- to 800-mile walkabout isn’t exactly understood, but the strong rainfall gradient of the ecosystem—with the wettest country in the northwestern woodlands and the driest in the Serengeti shortgrass plains, cast in the shadow of the Crater Highlands—establishes the foundation.

As David S. Wilcove notes in No Way Home: The Decline of the World’s Great Animal Migrations, among the leading hypotheses are that the greater nutritional content of the volcanic grasslands in the southeast draw the herds out of the north to give birth. It’s surely the case that the epic migration allows many more grazers to coexist in the same ecosystem than would otherwise be tenable.

The throngs of the Serengeti have special meaning, too, as the human animal came of evolutionary age in such sweeping, animal-filled savanna country.

South Sudan Migrations

The white-eared kob (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Another spectacular African migration plays out in the Boma-Jonglei landscape of South Sudan. It was only in 2007 that researchers confirmed that colossal numbers of large grazers still inhabited the region’s savannas, seasonally flooded grasslands, and swamps, even after decades of civil war. Perhaps more than 800,000 white-eared kob—stocky, handsome, medium-sized antelope—migrate between wet-season range in the northern reaches of Bandingilo National Park and dry-season pastures among the reliably green Guom and Gambella swamps in the South Sudan-Ethiopia borderlands, a journey of some 560 miles.

Part of their migration corridor overlaps that of another grazer, the tiang (a subspecies of topi), which also spends the rainy season around Bandingilo but which endures the thirsty months on the Jonglei Plains and the fringes of the Sudd wetlands of the White Nile floodplain. Mongalla gazelles mingle with the kob and tiang, forming far-traveling aggregations that may number more than a million.

Warfare, unrest, and the formidable obstacle posed by the Sudd wetlands appear to have preserved the great traveling herds of South Sudan, which certainly rival the Serengeti-Mara in magnitude. Oil development, refugee settlements, road-building, and the Jonglei Canal—an attempt to subjugate the vast swamp—pose potentially grave risks to these holdout migrations.

The Chobe-Nxai Zebra Migration

A herd of Burchell’s zebra (Photo: Ron Knight/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

A herd of Burchell’s zebra (Photo: Ron Knight/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

It was just in 2014 that an article in Oryx revealed another of Africa’s greatest terrestrial migrations: that of a herd of Burchell’s zebra in Namibia and Botswana. The wild horses hoof it some 150 miles between their dry-season haunts on the Chobe River floodplain of the Caprivi Strip down to Nxai Pan in northern Botswana. The two ends of this impressive pilgrimage—the Salambala Conservancy in the north and Nxai Pan National Park in the south—were well-known seasonal zebra ranges, but it took some adept GPS tracking on the part of researchers with the World Wildlife Fund, the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism, and Elephants Without Borders to reveal the migration link.

Unlike many great land-mammal journeys, the round of the Chobe-Nxai zebra is fairly secure: All of it takes place within an enormous international sanctuary, the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA).

Mule Deer Pilgrims of Western North America

A mule deer buck strides along the Red Desert-Hoback corridor (Photo: Joe Riis)

A mule deer buck strides along the Red Desert-Hoback corridor (Photo: Joe Riis)

Wildlife managers have long known about the seasonal travels of the mule deer in the American West: These widespread browsers, like elk in the same regions, typically spend their summers in the high country, then migrate downslope to low-elevation winter ranges to escape deep snow. It’s only recently that the full extent of these journeys—undertaken from the east-side Cascades and Sierra Nevada to the Colorado Plateau and beyond—has become clear. A 2011-2013 study funded by the Bureau of Land Management and headed by biologist Hall Sawyer revealed that wintering mule deer in south-central Wyoming’s Red Desert journey north in the spring as far as 150 miles to the Hoback Basin and surrounding mountains such as the Gros Ventre and Wyoming ranges.

This grand trip, which crosses a mosaic of public and private land and includes numerous road- and reservoir-crossings, ranks with comparable feats of pronghorn as the greatest terrestrial migrations in the lower 48 states and the second-longest on the continent after those of caribou. It also highlights Wyoming—a huge, sparsely populated state with a diverse roster of peripatetic ungulates—as a global migration hotspot.

The Mongolian Gazelle (Zeer)

A Mongolian gazelle (Photo: artvintage1800s.etsy.com/flickr)

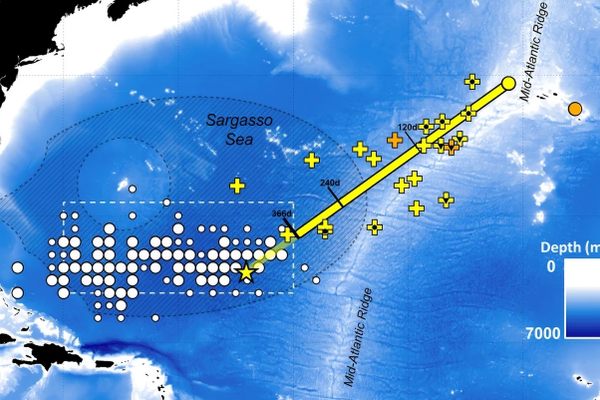

Since we no longer have the spectacle of thousands upon thousands of bison darkening the Great Plains to enjoy, enormous phalanxes of Mongolian gazelles on the move have become, perhaps, the grandest remaining migration across temperate grasslands. Even these prodigious herds—the biggest remaining of any ungulate in Asia—are but a shadow of historical ones; these fleet, compact grazers have declined dramatically in the face of habitat loss, having been mostly eliminated from former Russian and Chinese territory and now found almost exclusively on the steppes of eastern Mongolia.

Weaving from fresh pasture to pasture, sidestepping winter blizzards, crippling drought, and mosquito legions, Mongolian gazelles are essentially always in motion. Though their wanderings are perhaps best described as nomadic, they do migrate to specific wintering and calving ranges; some of these treks may eat up nearly 200 miles per day and muster ephemeral groupings of tens of thousands of animals. During the droughty summer of 2007, researchers came across such a “mega-herd” in Mongolia’s far east: perhaps more than 250,000 gazelles massed together in a vision from some Edenic past.

Roads, railways, and oilfields are increasingly pushing into the gazelle’s wilderness, threatening their ability to freely range between optimal habitat.

Pronghorn Peregrinations

A herd of pronghorn on the move. (Photo: Mark Gocke/U.S. Department of Agriculture/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

A herd of pronghorn on the move. (Photo: Mark Gocke/U.S. Department of Agriculture/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Perhaps the all-around speed champion of the animal kingdom, the pronghorn of western America’s sagebrush steppes and shortgrass prairies is also a world-class migrator, able to move through narrow passes with ease.Best-known of the pronghorn roads is the so-called “Path of the Pronghorn,” a 6,000-year-old corridor connecting summer range in Grand Teton National Park’s Jackson Hole flats and a winter refuge in the Upper Green River Valley some 160 miles south.

Among the topographic obstacles along this odyssey are four major river crossings and a 9,000-foot pass in the Gros Ventre Mountains. That high point, which can delay the herd if snowed in, is only one of several bottlenecks on the pathway. Another is Trappers Point near the town of Pinedale, where the pronghorn (as well as migrating mule deer) thread a half-mile-wide sagebrush interfluve between the Green and New Fork rivers. The archaeological record shows human beings, taking advantage of the narrows, have hunted pronghorn here for thousands of years. Such bottlenecks make pronghorn corridors especially vulnerable to roads, fences, and energy development, which, as in the antelope and gazelle rangelands of Asia, are squeezing the Grand Teton-Green River migration route.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s other surviving pronghorn migration is a more modest one: On the wildlife-rich Northern Range—the steppe and conifer savannas just north of the Yellowstone Plateau—some pronghorn that spend the winter around Gardiner, Montana journey eastward in spring to summer in and around the Yellowstone and Lamar valleys of northern Yellowstone National Park. A bottleneck exists here, too, on a ridge called Mount Everts near Mammoth Hot Springs: Because pronghorn dislike moving through heavy timber, they keep to slim throughways of grassland amid the mountaintop forest. (Their trepidation about the woods seems well placed: Several radio-collared pronghorn tracked over a six-year study of the migration were killed on Mount Everts by pumas.)

A lone pronghorn buck on the flanks of Specimen Ridge in Yellowstone National Park (Photo: Ethan Shaw)

A lone pronghorn buck on the flanks of Specimen Ridge in Yellowstone National Park (Photo: Ethan Shaw)

One herd of 100-200 pronghorn in south-central Idaho drifts between summer range in the Pioneer Mountains and wintering grounds along the Little Lost River and Birch Creek on the Snake River Plain, a round-trip trek of some 160 miles that skirts the petrified lava fields of Craters of the Moon. In 2013, meanwhile, biologists uncovered another large-scale migration in the shrub-steppe outback of the northwestern Great Basin: Many of the pronghorn that summer in Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge in southeastern Oregon and Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge in northwestern Nevada journey to a communal winter range around Beatys Butte.

The Chiru of the Tibetan Plateau

A chiru in Tibet (Photo: Yongzhoug Liu/flickr)

A chiru in Tibet (Photo: Yongzhoug Liu/flickr)

Endemic to the Tibetan Plateau, the chiru, also known as the Tibetan antelope, is another standout commuter of an ungulate: It may pace nearly 200 windswept miles between wintering and calving pastures that lie mostly above 13,000 feet.

Some chiru herds appear to be stationary, but researchers such as the eminent field biologist George Schaller have identified some four distinct populations in the northern Chang Tang Plateau, the species’s stronghold, which undergo seasonal travels. While bucks certainly wander, it’s the does that carry out the migration proper, heading north in the thousands through snow-skeined highland passes and across stark basins to specific summertime birthing grounds. Only pinpointed recently due to the remoteness and scale of the terrain, the austere nurseries are in the vicinity of several lakes in the Hoh-xil National Nature Reserve in Qinghai Province, and the desolate basins of a couple of saline lakes at the southern foot of the Kunlun Mountains.

Studies suggest these calving sites aren’t chosen for the nutritive value of their sparse grasses (typically just barely beginning to green up when the pregnant chiru arrive), but perhaps for the relatively low densities of predators and people. Some chiru migration paths seem to take rather irrational turns—traversing mountain ranges rather than adjacent valleys, for instance—which Schaller has speculated may reflect “vestigial” wayfaring established in the deep past, when some of those basins were waterlogged under substantial lakes.

Rampant poaching for the trade in the chiru’s undercoat wool (called shastoosh) as well as other factors led to a major range and population contraction for the antelope in the late 20th century; there may be anywhere from 75,000 to 150,000 left from a historical level of around a million animals.

The Gourma Elephants of Mali

A bull African bush elephant in South Africa (Photo: Profberger/Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

A bull African bush elephant in South Africa (Photo: Profberger/Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The farthest-roaming African elephants are also the northernmost left on the continent, a herd of some 350 that represents a last outpost for the species in the Sahel. The elephants of Gourma migrate more than 300 miles in the semidesert of south-central Mali and the extreme northwest of Burkina Faso. With adults often segregated by sex, they typically follow a roughly circular, north-south path that encompasses an astonishing 12,355 square miles—a significantly vaster range than any other tuskers in Africa.

In a study published in a 2013 issue of Biological Conservation, researchers with the Save the Elephants organization installed GPS collars on nine Gourma pachyderms to track the migration. The project, which suggested the annual journey may revolve around shifts in the nutrient content of the animals’ favored browse, identified several bottlenecks along the migration route—including a mile-wide pass through a sandstone massif that locals call la Porte des Elephants, “the Elephant Doorway”—as well as “hotspots” where the herds seemed to linger.

These remnant North African elephants have long shared their remote Sahel range with low densities of local peoples and their livestock, including nomadic Tuareg and Fulani herders. They and their ancient footloose tradition are under threat, however, from increasing human pressures—including a local shift from pastoralism to agriculture–as well as climate change and most pressingly, increased poaching.

The Saiga of Central Asia

Saiga antelopes (Photo: BBH/shutterstock.com)

Saiga antelopes (Photo: BBH/shutterstock.com)

Possessed of a swollen nose and coil-spring horns, the saiga is a thoroughly eccentric-looking antelope. Originally native to steppes and semideserts from eastern Europe to Central Asia, the saiga’s stomping grounds have collapsed over the past century or so due to overhunting and land-use alteration. Remaining herds—reduced from historical numbers by more than 95 percent—inhabit widely scattered ranges in Kazakhstan, Russia’s Precaspian region, and western Mongolia. According to a 2010 review of saiga migrations, Kazakhstan’s Betpak-Dala herd may trek more than 700 miles one-way between winter and summer ranges, pacing up to 50 miles in a single day.

The already-precarious status of the saiga has worsened in recent years due to mysterious epidemics, the most recent and deadly of which struck Kazakhstan in May of 2015. At present, more than 120,000 animals—more than one-third of the entire population—have perished from an ailment scientists are struggling to identify.

A male saiga antelope (Photo: Yakov Oskanov/shutterstock.com)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook