How New York City’s Electrical Utilities Observed the 1925 Eclipse

The predecessors to ConEdison wanted to know how an eclipse affected the grid.

As Sun is blocked by the Moon on August 21, solar power production across the United States will drop by about five gigawatts. Utility companies say there won’t be blackouts, but they are concerned about the impact of the eclipse on the electrical grid. The 2017 eclipse is an important chance to track the effects of an eclipse on solar power and learn lessons that will be useful in 2024, when another eclipse will sweep from Texas to Maine. But this isn’t the first time utilities have paid close attention to the grid during a solar eclipse. Back in 1925, the electrical companies serving New York City were interested in the eclipse that passed over Manhattan, and set out to measure its impact.

On January 24, 1925, the total solar eclipse was visible from Minnesota, across the Great Lakes, to New York. The Consolidated Gas Company and the New York Edison Company (who have since merged and are known today as ConEdison) decided to join in scientific investigations happening during the celestial event. “It was felt that some of the industrial and social aspects of the extraordinary phenomena, as affecting the light and power services in the territory involved, would be of interest,” wrote John W. Lieb, the vice president and general manager of the New York Edison Company at the time. Lieb penned the forward to a small pamphlet released by Consolidated Gas after the eclipse, which detailed the results of their experiments. These efforts included measuring the exact southern edge of the path of totality, gauging the change in sunlight intensity, and assessing the impact of the eclipse on the electrical grid. They also sought to answer another question: Should the street lamps be turned on “in the zones traversed by the stupendous cosmic shadows”?

To find the exact edge of totality, the companies positioned people on rooftops along Riverside Drive, on the western shore of Manhattan. The New York Times had predicted on January 23 that the southern edge would cross Manhattan at 83rd Street, but observers with the electrical companies stretched from 71st Street to 134th Street. One man on each rooftop was supposed to “look a little north of west to watch the oncoming shadow.” And another was responsible for watching the eclipse to see if the Moon completely covered the Sun from each vantage point. Their observations were compiled, and “it was possible to establish a definite line between No. 230 Riverside Drive (just south of 96th Street) and No. 240 Riverside Drive (just north of 96th Street).” The two rooftops were separated by about 225 feet, and the estimate given the day before was off by about 13 blocks.

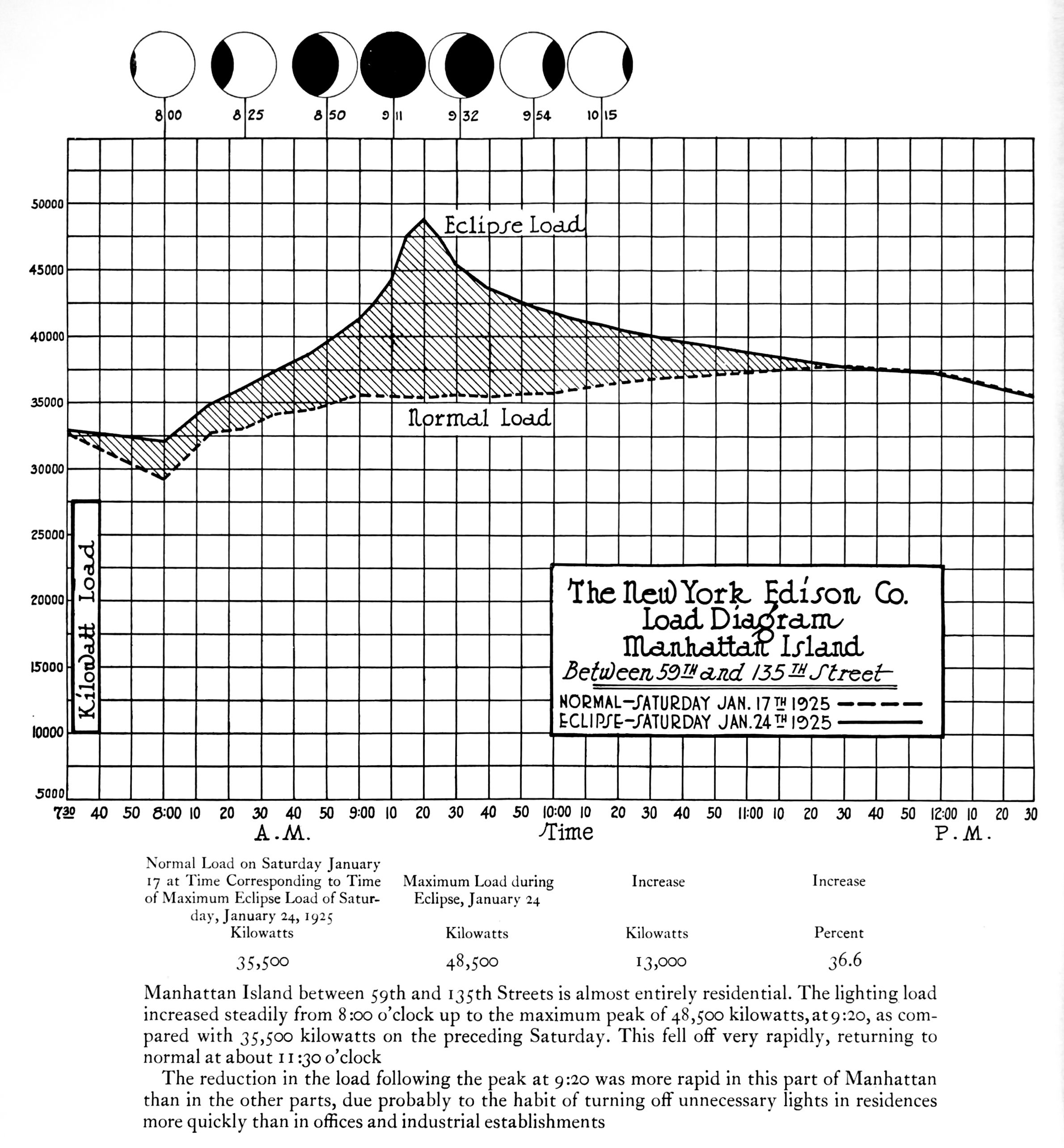

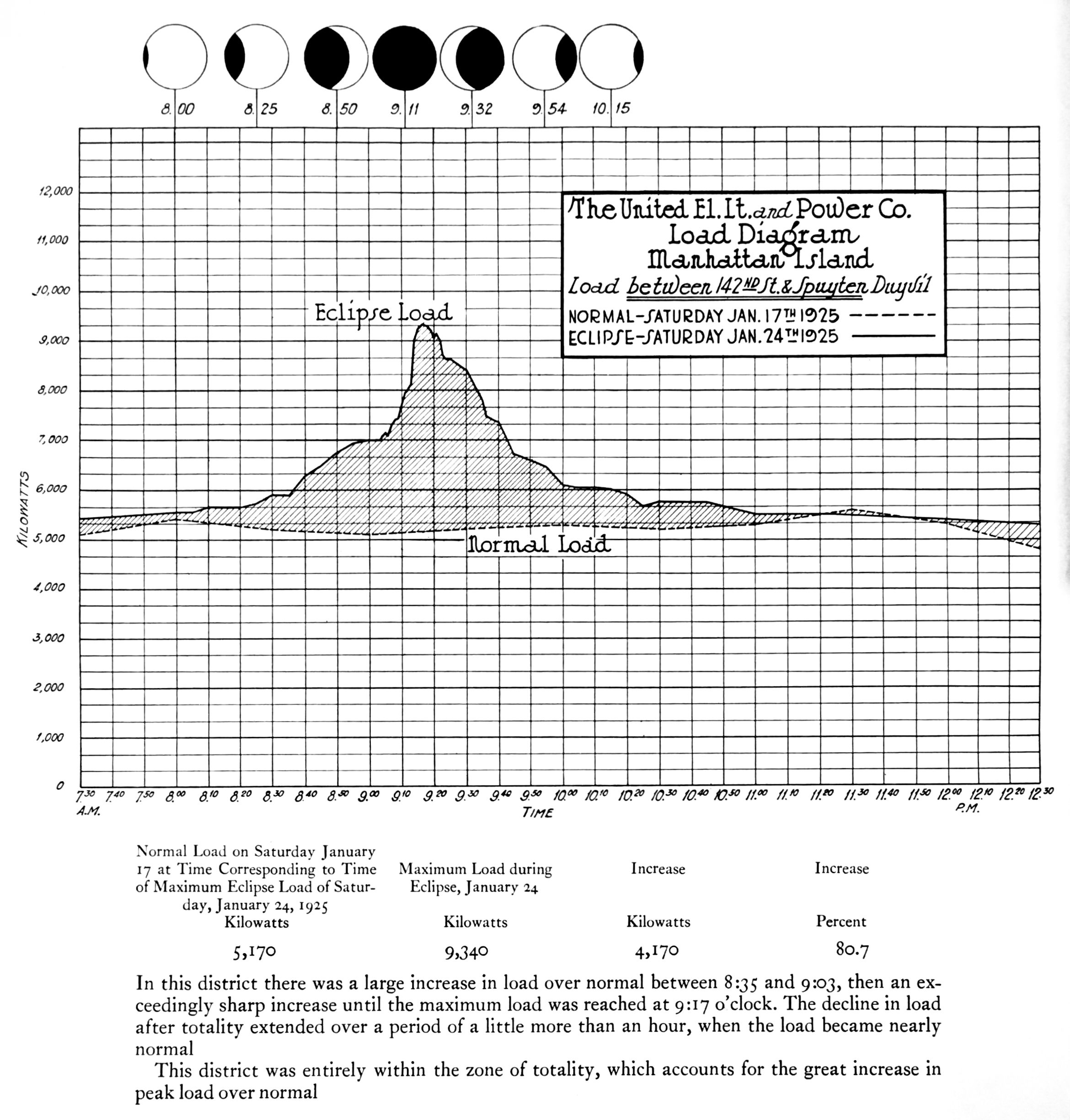

While employees from the New York Edison Company recorded the intensity of sunlight (during totality it was “comparable to a moonlight night”), employees of other electric companies throughout the region were carefully recording the load on their grids at regular intervals. Not everyone chose to brave the bitterly cold temperatures that day—electricity demand spiked as the sky darkened. But demand didn’t drop suddenly once the eclipse was over. The author of the pamphlet explains, “The failure to return to normal soon after the eclipse is the usual condition following any reduction in normal daylight, as people turn on lights and then neglect to turn them off.”

Some areas, including the Bronx and Yonkers, actually saw a reduction in loads because businesses gave their employees the day off. And while the area had been hit with a snowstorm about a week before, electrical loads came entirely from lighting, not heat. “In New York at that time, most people heated their homes, believe it or not, with coal,” says Bob McGee, a spokesperson for ConEdison.

If a total solar eclipse occurred over New York City today (something that won’t happen until May 2079), McGee says it wouldn’t have an effect on the electrical grid. “If anything, it will mean people use less electricity,” he says. If the eclipse were to happen in summer, when hot weather has people turning on their air conditioning, a brief respite from the sun might convince people to take a break from cooling their homes and businesses. Otherwise, he says, “it wouldn’t be any more of a problem than the use at night.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook