A Beginner’s Guide to Body Snatching

Where to go for an education in grave robbery, the grisliest chapter in medical history.

Say it’s 1820 and you’re an uneducated, lower-class chap with nights and weekends free who needs to pick up a few extra quid. You might consider the profitable, if criminal, profession of body snatching.

In the early days of surgery, dissecting a corpse was seen as a heinous defilement of the body, akin to cannibalism in its vulgarity. But the growing field of surgical science demanded bodies for study. The gallows were the only place surgeons could get cadavers. Executed criminals were fair game to slice and dice, as were suicide victims, but not regular law-abiding corpses. Even in the crime-riddled streets of London and Edinburgh, there weren’t enough bodies to train the new classes of young surgeons in the growing field.

So intrepid anatomists determined to educate their students would hire a body snatcher. It was a simple case of supply and demand. The surgeons needed bodies to dissect, and out-of-work men knew just where to find them: cemeteries, of course.

People had been robbing graves practically since humanity began burying its dead, usually for jewelry or money, but never had the corpse itself been so valuable. A league of “resurrection men” (so called because they “resurrected” the dead) took to the streets in the dead of night. In middle class cemeteries a watchman could be given a cut to look the other way. In the graveyards of the less prosperous where there was no such guard snatching was considerably easier. Fresh bodies were obviously preferable, so they would browse funerary announcements to find out where the newly dead would be buried.

The resurrectionists would dig a small hole near the head of the coffin then drag the body out with a rope. Clothing and jewelry were left behind; stealing those could be considered a felony, but if they were caught stealing a body it was only a misdemeanor. The grave would be filled back in and mourners might never know a grave was empty.

In The Diary of a Resurrectionist, dated January 13, 1812, a resurrection man details his work over the course of a night:

“Took 2 of the above to Mr Brookes & 1 large & 1 small to Mr Bell. Foetus to Mr Carpue. Small to Mr Framton. Large small to Mr Cline. Met at 5, the Party went to Newington. 2 adults. Took them to St Thomas’s.”

“Large” here refers to adults, while “small” refers to children. Clearly, no grave was safe from the body snatcher’s shovel. In fact, anatomists would have been glad to receive bodies that were not adult men. Bodies of children and women, particularly pregnant women, were a rare and desirable (if macabre) commodity.

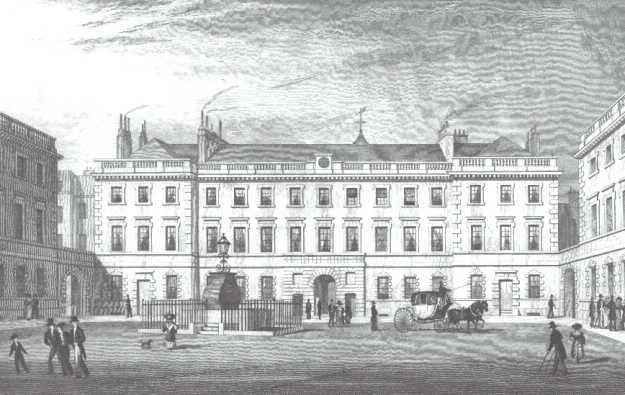

Other entries from the resurrectionist’s diary include reference to selling just the extremities of a body to places like St. Thomas’ and St. Bartholomew’s reputable hospitals, whose body purchases were done on the sly. Their operating surgeons would meet the grave robbers in back doors and alleyways to buy the stolen corpses in the wee hours of night. The operating theatres at St. Thomas and St. Bart’s, where stolen cadavers would have been dissected for anatomy lectures, now operate museums dedicated to this crime-enabled medical history.

Saint Thomas Operating Theatre

LONDON, ENGLAND

Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital Pathology Museum

LONDON, ENGLAND

Body snatchers were the lowest of low criminals. Practically every entry in The Diary of a Resurrectionist ends with, “all got drunk.” They were disreputable characters known to congregate in the seedy end of London. One of these sites was commemorated as early as the 1660s in an inscription under the city’s Golden Boy statue.

The Golden Boy at Pye Corner

LONDON, ENGLAND

But it wasn’t until the infamous Anatomy Murders that grave robbers were labeled as a public menace that had to be stopped.

William Burke and William Hare lived in Edinburgh in 1828. Burke made his money hawking secondhand clothes to paupers, Hare made his by renting his rooms out to lodgers. When one of his tenants was found dead, the pair decided to compensate for the lost wages from the dead lodger by selling his body to the anatomists at Edinburgh University’s Surgeon’s Square. The esteemed Dr. Robert Knox, father of modern anatomy, paid them £7 for the body. The two resurrectionists were told the surgeons “would be glad to see them again when they had another to dispose of.”

Burke and Hare took Knox up on his offer. When a subsequent lodger showed symptoms of cholera, Hare and his wife agreed it would be unseemly to allow her to stay on the premises with other guests. He and Burke smothered the woman and brought her body to the Royal College of Surgeons. This time they were paid £10, and Dr. Knox commended them on the freshness of the body.

Their killing spree went on like this. Burke and Hare would murder unsuspecting lodgers and drifters in their sleep, sometimes sedating them with liquor first, then they would bring them to Dr. Knox. The bodies were used in anatomy lectures, where on more than one occasion students’ claims that they recognized the deceased were waved away.

Eventually another lodger found the undelivered body of Burke and Hare’s final victim hidden in a haystack. Their business was traced back to the Royal College of Surgeons. Knox claimed innocence of the murders and was exonerated. Burke and Hare were tried and convicted for the killing of 17 people, the former receiving the death sentence while the latter was merely jailed temporarily.

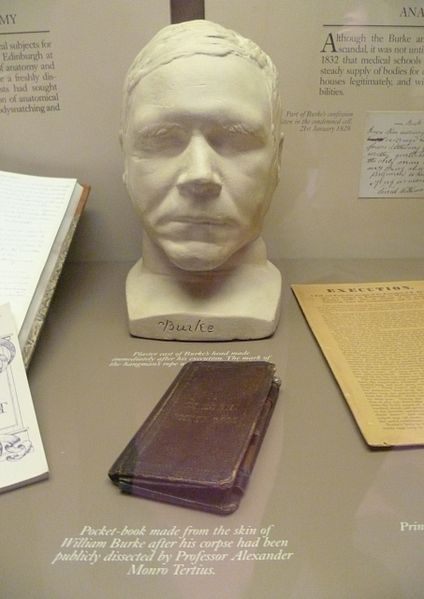

In an ironic twist of fate, Burke’s body was donated to the Royal College of Surgeons, supplying the institution one final time. He was dissected before a sold-out lecture, a letter was written in his blood, his skeleton put on display, and his skin was used to bind a book and a wallet.

Surgeons’ Hall Museum

EDINBURGH, SCOTLAND

A media firestorm ensued. Newspapers ran with the salacious story of the two murderers supplying the vicious field of surgery. Copycats followed: The “London Burkers” were arrested in 1831 for a series of similar murders. Mysteriously, just a few years after the Anatomy Murders two young boys discovered dolls depicting Burke and Hare’s victims hidden in a park. Who made the dolls or why is still unknown.

Burke and Hare Murder Dolls

EDINBURGH, SCOTLAND

The public was terrified by these increased reports of grave robbery. Death rites were sacred for the Georgians, as evidenced by the highly specific mourning customs that evolved over the 19th century. To have your loved one’s ceremonious wake and funeral capped off by a disgraceful dismemberment was the ultimate affront to class and society, not to mention just disrespectful and icky. Families feared that body snatchers were coming for their dear deceased, and funneled even more money into funerary costs to protect against grave robbing. These measures included installing permanent mortsafes, giant metal cages atop the graves. An example can still be seen at Greyfriars Cemetery in Edinburgh.

Greyfriars Cemetery Mortsafes

EDINBURGH, SCOTLAND

In Scotland two popular solutions arose. One was morthouses, circular buildings in graveyards where coffins would be stored until the bodies inside were too rotten to be of any use to anatomists and their hired snatchers. The second solution was to hire a watchman, either for one specific grave or the entire burial ground. The round, squat buildings constructed to protect the watchmen from the elements are still visible in some cemeteries. The manor cemetery at Boleskine House, for one, features a watchman’s shelter, which is linked to the house cellar by a mysterious underground tunnel.

Boleskine House

FOYERS, SCOTLAND

A more unbelievable (and sadly, more difficult to find) anti-grave robbing mechanism was the cemetery gun. It was a spring-loaded revolver, trip wired to shoot at anyone trespassing in a cemetery when they shouldn’t be. An example of this rare cemetery gun is on display at the Museum of Mourning Art in Pennsylvania.

Museum of Mourning Art

DREXEL HILL, PENNSYLVANIA

Though the phenomenon of grave robbing is most often linked to the United Kingdom, it certainly occurred in the United States. Human remains believed to be stolen have been found in medical institutions from the Medical College of Georgia to Harvard University. While corpses stolen in the U.S. were more often snatched from black cemeteries and potters’ fields, there was at least one occasion of body snatching at the cemetery St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery and another from New York’s historic Trinity Churchyard. Both of these, unsurprisingly, caused a greater stir than the theft of any poor person of color’s body.

Trinity Churchyard

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

A crackdown on body snatching came in the wake of the Burke and Hare murders and London Burkers. British Parliament enacted the Anatomy Act of 1832, loosening restrictions around the procurement of bodies for anatomy courses. In addition to bodies of the executed, bodies of prisoners, orphans, and unclaimed corpses from the morgue were all fair game for anatomy lessons. Additionally, several doctors put out a call to their aging brethren to donate their own bodies to science. A few took up the challenge. Graves were no longer violated in the name of medical progress.

Anatomy labs are no longer the leering event they were in the 19th century. Civilians, as well as dedicated scientists, today donate their bodies after death, and modern med schools frequently include a funeral service to honor the anonymous body on their slabs.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook