A Brief Guide to Impractical Currencies

In modern economies, we use an agreed-upon medium of exchange, or currency, to trade with merchants, corporations, and our neighbors. Throughout history, this has most often been domestic animals, agricultural staples like rice and barley, salt, beads, cowry shells, precious metal, and government-backed legal tender. These are things that can be led or carried by the owner. However, what if your currency is an enormous limestone disc that can be over three meters in diameter and weigh four metric tons? What if it is a shovel blade that one can put the handle back in and use in the field? Some agreed-upon currencies used throughout history, and even in the modern day, we would consider impractical.

Yap stone in Micronesia (photograph by tata_aka_T/Flickr)

Yap stone in Micronesia (photograph by tata_aka_T/Flickr)

On the Micronesian island of Yap stand the Rai stones. Limestone is a very rare mineral in this area of the Pacific. The stone was quarried mainly from the island of Palau, with Guam supplying some for a time as well. Originally fashioned into the shape of fish, and later as circular discs, these stones are still used today, though mainly for social transactions like marriage by the Yapese. Instead of carrying these behemoths across the island, giving the stone can be as simple as saying it belongs to a new owner, and the “bank statement” would be the oral history of the stone’s possessors. Not all Rai stones are colossal, and vary in value by their history, as well as size. Even a stone that sank into the ocean is still considered owned, because it is agreed upon that the stone is still there, and it has a history.

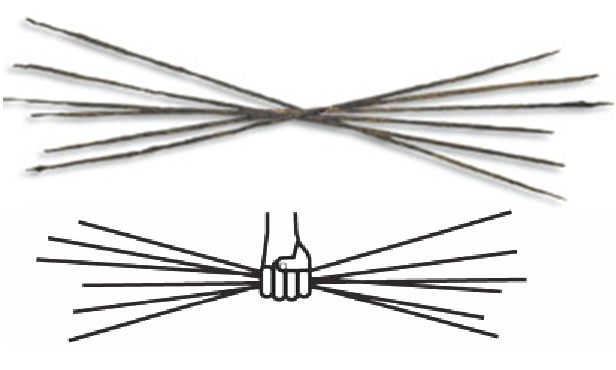

In ancient Greece, rods of various metals were used as currency before coins. These are the oboloi (singular obolos, or obol in English) — rods of iron, copper, or silver about a meter in length. In Athens, six oboloi equaled one drachma, meaning “handful.” The word passed into usage as the name of Greece’s currency until the euro was adopted. Even after the introduction of coins, Plutarch wrote that Sparta kept using oboloi to discourage the pursuit of wealth over deeds in battle. One obolos could buy a ritual cup with wine.

A drachma of oboloi (via Odysses/Wikimedia)

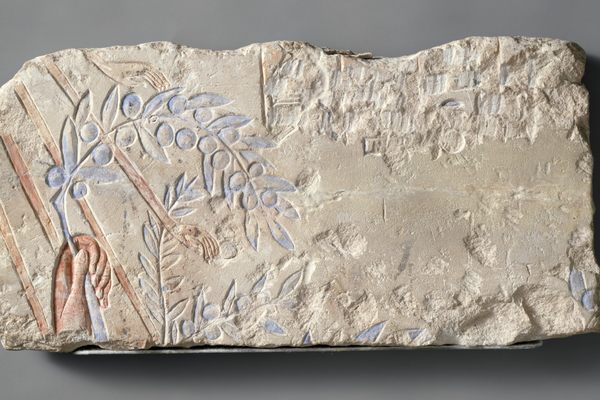

In Zhou Dynasty China, there are two examples of tools being used as currency. Spades and weeding tools with the handle taken off were used in northeast China. This is known as spade money. When first used, the spade kept the hole so the handle could be reattached. In time, the money of the area and era kept the spade shape, but shrank to a more manageable size. In some areas, various stories took hold about how knives became traded, and then for 400 years, knife money became the currency. These knives weren’t edged, but they did have the same shape and dimensions as common knives of the time.

Spade money with hole for the handle (photograph by Davidhartill/Wikimedia)

Spade money with hole for the handle (photograph by Davidhartill/Wikimedia)

Knife money from the Capital Museum, Beijing (photograph by Yanan Peng/Wikimedia)

Knife money from the Capital Museum, Beijing (photograph by Yanan Peng/Wikimedia)

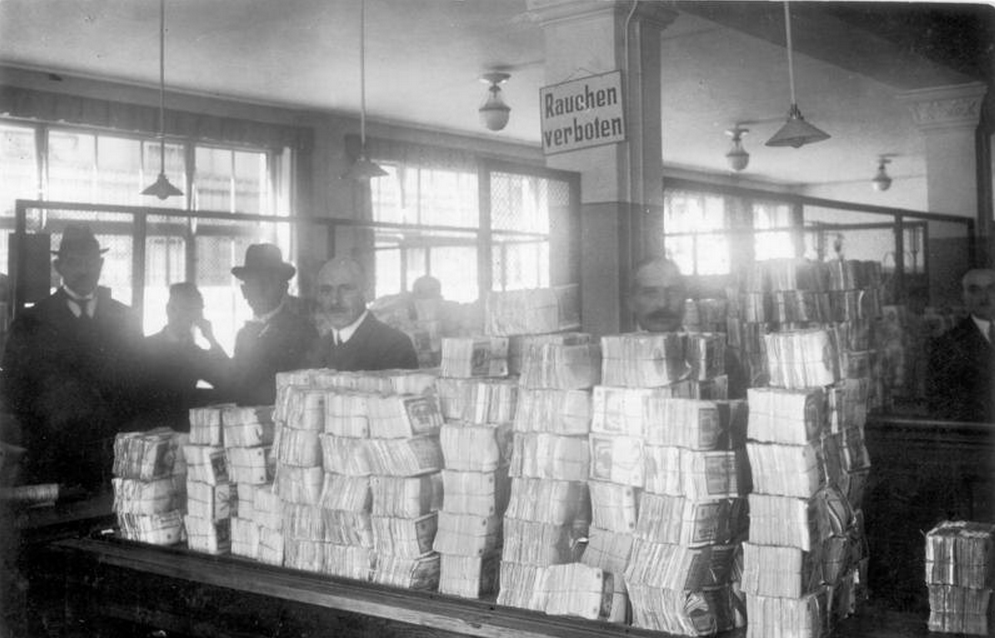

Impractical currencies aren’t just limited to isolated and ancient societies. Throughout modern history, instances of hyperinflation, where the rate of inflation skyrockets due to factors such as war or political instability, make currencies worth less and less in a short length of time. To compensate, the government prints out large quantities of ever higher denominations of bills. In Weimar Germany in 1923, the price of a loaf of bread went from 1.5 million Marks in September to 200 billion Marks in November. Citizens had to shop with wheelbarrows full of rapidly depreciating Marks, or all that currency would be next to worthless in the next few days.

In Hungary after World War II, all Hungarian pengő in circulation amounted to 1/1000 of a US dollar, with an inflation rate of 41.9 quadrillion percent in 1946. In Zimbabwe at the height of its recent hyperinflationary period, images were shown in the news of people carrying stacks of multi-billion and multi-trillion dollar bills wrapped with rubber bands. After the government had printed 100-trillion dollar bills in 2009, the Zimbabwe dollar was abolished. The ludicrously high denomination bills from this period are still inexpensive collectors’ items, with the 100-trillion dollar bill costing about 30 US dollars today.

Stacks of hyperinflationary Weimar Germany Marks (via German Federal Archives)

Stacks of hyperinflationary Weimar Germany Marks (via German Federal Archives)

With the holiday shopping season soon to be upon us, consider how easy it is to not have to take the cashier to your Rai stone, pay with agricultural supplies or long metal spits, or take a wheelbarrow full of bills and count out a figure in the quintillions. Your wallet, and back muscles, will thank you.

Hey, buddy, can you spare a few trillion? (photograph by the author)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook