A Mummy Hoax Might Be Wrapped up in a Modern Murder

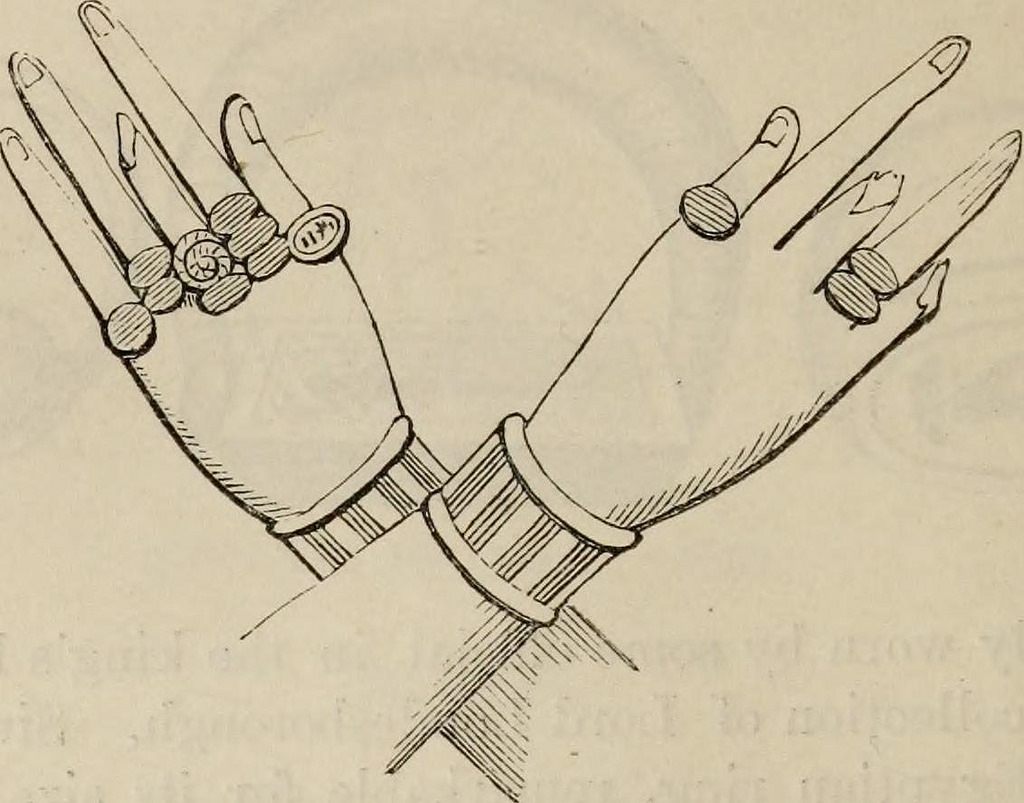

Mummy case hands in the “Handbook of archaeology, Egyptian - Greek - Etruscan - Roman” (1867) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Mummy case hands in the “Handbook of archaeology, Egyptian - Greek - Etruscan - Roman” (1867) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

In October of 2000, Pakistani authorities heard that a Karachi resident was trying to sell a mummy on the black market for $11 million. When the police interrogated the seller, he told them he got the mummy from an Iranian man, who supposedly found it after an earthquake, and the two agreed to sell it and split the profits. The seller eventually led them to where he was storing the mummy, a region that borders Iran and Afghanistan.

Pakistani authorities brought the mummy to the National Museum in Karachi, where museum officials inspected the remains and its sarcophagus. Museum officials announced that a mummy wrapped in an Egyptian style had been recovered in a wooden sarcophagus with cuneiform inscriptions, the written language of ancient Persia, and carvings of Ahura Mazda, a Zoroastrian deity. The mummy had a golden crown, mask, and a breastplate that proclaimed, “I am the daughter of the great King Xerxes. Mazereka protect me. I am Rhodugune, I am.” This meant that this mummified body potentially belonged to a Persian princess and was 2,600 years old.

The mummy of the Persian Princess generated a lot of international interest because no remains of the Persian royal family had ever been found and mummies are not generally found in Iran. At one point the mummy caused diplomatic tensions between Iran and Pakistan because both countries claimed ownership. But months later, after examinations by experts in ancient Persian script, CT scans, chemical testing, and carbon dating, the mummy was not only declared a fraud, but there was also evidence that she may have been a modern murder victim.

Scholars grew suspicious of the mummy’s authenticity when experts in ancient cuneiform examined the mummy’s breastplate and determined that someone “not well familiar with Iranian script,” had carved the inscription.

This mummy hoax began to unravel after subsequent testing.

CT scans revealed that the mummy belonged to an adult woman who was about 4 feet 7 inches tall and was older than 21 years old when she died. The scans also showed that all of her internal organs had been removed, and her abdominal cavity had been filled with a powdery substance. An autopsy exposed that the cause of death was a broken neck caused by blunt force trauma to the cervical vertebrae. But a forensic pathologist could not determine if the woman’s neck had been broken deliberately.

Chemical analysis indicated her body and hair had been bleached and her abdomen had been filled with modern drying agents, like bicarbonate of soda and sodium chloride. The results of carbon dating on bone and tissue revealed that the remains belonged to a woman who had died in 1996.

Investigators believe that the perpetrators of this fraud obtained a fresh corpse from grave robbers who looted a burial from the area between Pakistan and Iran. The forgers then removed the corpse’s internal organs and covered the body with chemicals to dry the body over the course of months. This was an intricate forgery that took months to execute and had to involve scholar(s) and someone familiar with anatomy.

The evidence of the broken neck caused Pakistani police to open a murder investigation for which they re-interrogated the middlemen involved with the black market sale. They hoped to identify the woman and her murderer, but so far this remains a cold case.

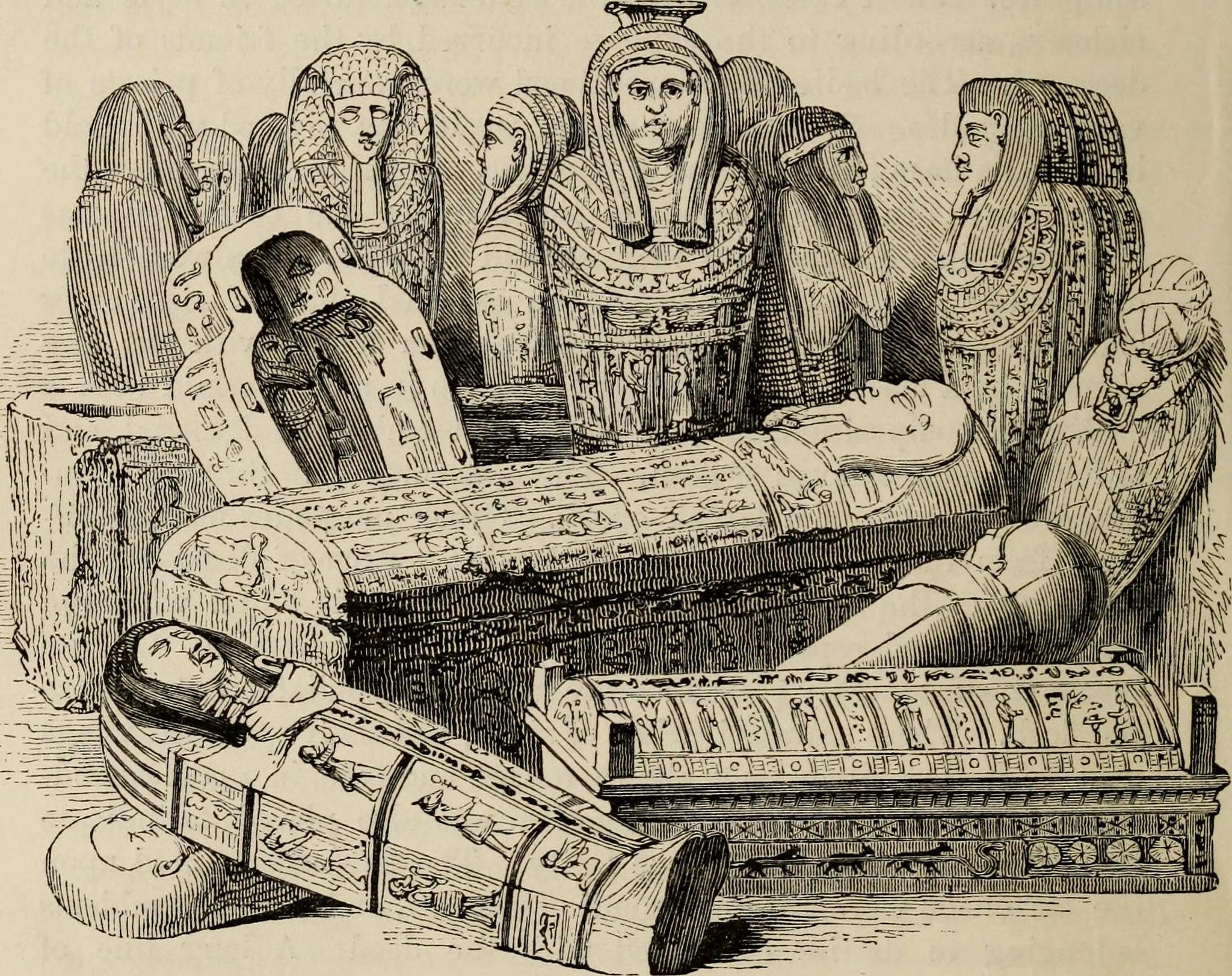

Mummy cases & sarcophagi from “Handbook of archaeology, Egyptian - Greek - Etruscan - Roman” (1867) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Mummy cases & sarcophagi from “Handbook of archaeology, Egyptian - Greek - Etruscan - Roman” (1867) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

For more fascinating stories of forensic anthropology visit Dolly Stolze’s Strange Remains, where a version of this article also appeared.

Morbid Mondays highlight macabre stories from around the world and through time, indulging in our morbid curiosity for stories from history’s darkest corners. Read more Morbid Mondays>

References:

Hill, B (Interviewer), Ibrahim, A (Interviewee), and Professor Milroy, C (Interviewee). (2001). The Mystery of the Persian Mummy [Interview transcript]. Retrieved on November 14, 2014 from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2001/persianmummytrans.shtml

Koenig, R. (2001). Modern Mummy Mystery. Retrieved on November 14, 2014 from: http://news.sciencemag.org/2001/06/modern-mummy-mystery

Romey, KM and Rose, M. (2001). Special Report: Saga of the Persian Princess. Retrieved on November 14, 2014 from: http://archive.archaeology.org/0101/etc/persia.html

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook