A Religious Cult Believed They Could Be Reborn Inside Mount Fuji’s ‘Womb Caves’

A 19th-century map describes a hidden network of lava caves.

Around 1848, Japan’s tallest peak, Mount Fuji, was depicted in a multicolor panoramic woodblock map. Amid the intricately illustrated trails, vegetation, and turf, this print featured an unusual paper flap. When flipped over, painter Utagawa Sadahide reveals the network of lava caves hidden deep inside the core of the active 12,388-foot volcano.

For centuries, religious devotees, or ascetics, looked towards Mount Fuji as a place of worship, trekking up the mountainside to reap its spiritual powers. The mysterious lava caves (labeled 3 on the map above) were thought of as “human wombs,” and those who journeyed through the dark passageways could experience rebirth.

“Mountain ascetics in Japan, including those devoted to Mount Fuji, experience ritual death and rebirth in their rites in the mountain,” says Fumiko Miyazaki, who analyzed the unique map of Mount Fuji in the book Cartographic Japan: A History in Maps. By practicing and passing through the caves, “an ascetic imagined that he or she gives up his or her old self stained with sin to reappear as a better person in the world.”

Mount Fuji, one of the Three Holy Mountains in Japan. (Photo: skyseeker/CC BY 2.0)

There are hundreds of caves on the flanks of Mount Fuji. Many of the caves formed as the mountain continued to shift and change over years of volcanic eruptions and activity. When lava flowing down from the crater reached the forest on the lower regions of the mountain, it coated trunks of large trees which collapsed and were coated with lava. As the trees cooled, they rotted away and left behind caves. Many caves on the northern side of the mountain, including the caves close to the Yoshida entrance Sadahide drew in the map, are said to be a byproduct of a large-scale eruption in 937, explains Miyazaki.

Devotees and pilgrims of the cult of Mount Fuji often ventured through the chain of caves either on their way to Mount Fuji or on their descent back. While many of the caves were used for spiritual practices, there was one “womb cave” that has been singled out as the mother of all caves at Fuji, writes H. Byron Earhart in the book Mount Fuji: Icon of Japan.

The cave known as Tainai, which translates to ”womb,” is said to be the birthplace of Sengen, the deity of Mount Fuji. It was common for the religious followers of the Mount Fuji cult to associate terrestrial features of the mountain with parts of the human anatomy, Earhart explains.

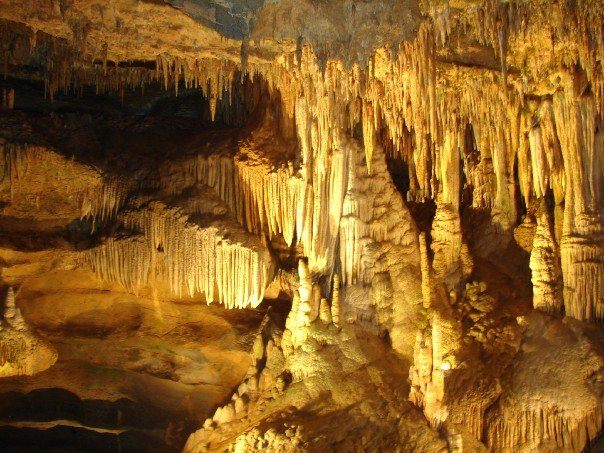

Pilgrims collected “milk” from the stalactite “breasts.” (Photo: Public Domain)

Certain rocks were called navel cords or placentas, while bell-shaped stalactites were referred to as breasts, the water dripping down considered milk of the mountain. A person who crawled through the cave carried a white cotton cloth that was used to collect the milk dripping from the rock breasts.

Once soaked, the cloth was brought back down and used for several purposes for pregnant women and new mothers. The cloth was placed in a mother’s drinking water so the powers from the mountain could aid in delivery or help mothers or nursing women who could not produce breast milk.

The dark cavern of Tainai had low ceilings, and the pilgrims would place straw sandals on their knees to protect them while they crawled. They lit candles to find their way through the cavern, and brought the candles home when family mothers gave birth. Shorter candles (ones that burned for longer in the cave) were thought to aid in short labor and quick delivery.

One of the caves in Mount Fuji. Pilgrims carried sacred candles to light their way through the dark spaces. (Photo: Soramimi/CC BY-SA 4.0)

One of the caves in Mount Fuji. Pilgrims carried sacred candles to light their way through the dark spaces. (Photo: Soramimi/CC BY-SA 4.0)Sadahide was very familiar with Mount Fuji’s terrain and lava caves. He had climbed the mountain several times, and sketched all his observations for the 19th century panoramic map. In addition to the topography of the mountain, Sadahide was interested in what was inside the mountain. He had also published a three-sheet painting titled “Fujisan tainai meguri no zu” that shows pilgrims journeying within the caves.

Practicing meditation and prayer inside caves was an integral part of Japanese mountain religion. Sadahide’s map highlights two holy men sitting in caves in the center of the woodblock. Kakugyō Tōbutsu and Jikigyō Miroku (labeled 2 on the map) are two important founding figures of the Mount Fuji cult.

Sometime around the turn of the 17th century, Kakugyō (the man on the left) founded another famous spiritual cave on the western flank of the mountain called Hito-ana, literally “man hole.” According to legend, Hito-ana was believed to be the deity’s residence and an entrance to another world. Kakugyō, who has been deemed the father of the Mount Fuji cult, sought the power of the mountain and received a prophecy to go to the cave. He became known as the man in the cave, residing and practicing in the Hito-ana for seven days.

“Complete Portrayal of the True Features of Mount Fuji.” Here, a replica by the Kanagawa Prefectural Museum is folded into a cone. (Photo: Kohga Communication Products Inc., Yokohama, Japan)

“Complete Portrayal of the True Features of Mount Fuji.” Here, a replica by the Kanagawa Prefectural Museum is folded into a cone. (Photo: Kohga Communication Products Inc., Yokohama, Japan)

The “Portrayal of Mount Fuji” can also be folded into a three-dimensional cone that better represents the mountain and its features. When laid flat, you can see Kakugyō and Jikigyō sitting in two caves. Then, when transformed into its cone shape, the two men disappear into the mountain where they belong.

“I am impressed by the device of the painter to make a three-dimensional map,” says Miyazaki. “I have never seen a three-dimensional picture of a famous mountain except for it.”

Not everyone could revel in wonders of Mount Fuji’s lava caves. Until 1868, women were banned from climbing higher than the middle zone of the mountain, ascetics worrying that they would distract men from their religious duties and other traditional taboos. Some male devotees also couldn’t climb due to physical or economic reasons.

“For such people, the picture-map could function as a medium for imagining more fully the sacred places that they could never see in reality,” Miyazaki writes in Cartographic Japan: A History in Maps.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook