Mapping the Many Monsters of Aboriginal Australian Lore

A “terrifying pantheon” of ogres, sorcerers, and malevolent mermaids reflects a diversity in geography and environment.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

A rich inventory of monstrous figures exists throughout Aboriginal Australia. The specific form that their wickedness takes depends to a considerable extent on their location. In the Australian Central and Western Deserts there are roaming ogres, bogeymen (and bogeywomen), cannibal babies, giant baby-guzzlers, sorcerers, spinifex, and feather-slippered spirit beings able to dispatch victims with a single fatal garrote. There are lustful old men who, wishing to satiate their unbridled sexual appetites, relentlessly pursue beautiful, nubile young girls through the night sky and on land, and other monstrous beings, too.

Arnhem Land, in Australia’s north, is the abode of malevolent shades and vampire-like wind and shooting star spirit beings. There are also murderous, humanoid fish-maidens who live in deep waterholes and rockholes, biding their time to rise up, then grab and drown unsuspecting human children or adults who stray close to the water’s edge. Certain sorcerers gleefully dismember their victims limb by limb, and there are other monstrous entities as well, living parallel lives to the human beings residing in the same places.

The existence of such evil beings is an unremarkable phenomenon, given that most religious and mythological traditions possess their own demons and supernatural entities. Monstrous beings are allegorical in nature, personifying evil.

In the Christian tradition, we need to look no further than Satan. In the Tanakh, ‘The Adversary,” as a figure in the Hebrew Bible is sometimes described in English translation, fulfills a similar role. Often, akin to many of the monstrous beings that inhabit Aboriginal Australia, these evil supernatural entities are tricksters, shape-changers and shape-shifters.

The trope of metamorphosis is evident in the real-life stories and media representations in Australia’s dominant culture: Consider the image of the kindly old gentleman next door or the devoted, caring parish priest who shocks everyone by metamorphosing into a child-molester, creepy, predatory, though ever-charming.

As the celebrated British mythographer and cultural historian Marina Warner has noted:“Monsters are made to warn, to threaten, and to instruct, but they are by no means always monstrous in the negative sense of the term; they have always had a seductive side.” Warner also observes that mythical, malevolent beings are found the world over. Think of Homer’s Cyclops, the night-hag of Renaissance legend or the German Kinderfresser, which snatches and eats its young victims. Such beings embody people’s deepest anxieties and fears.

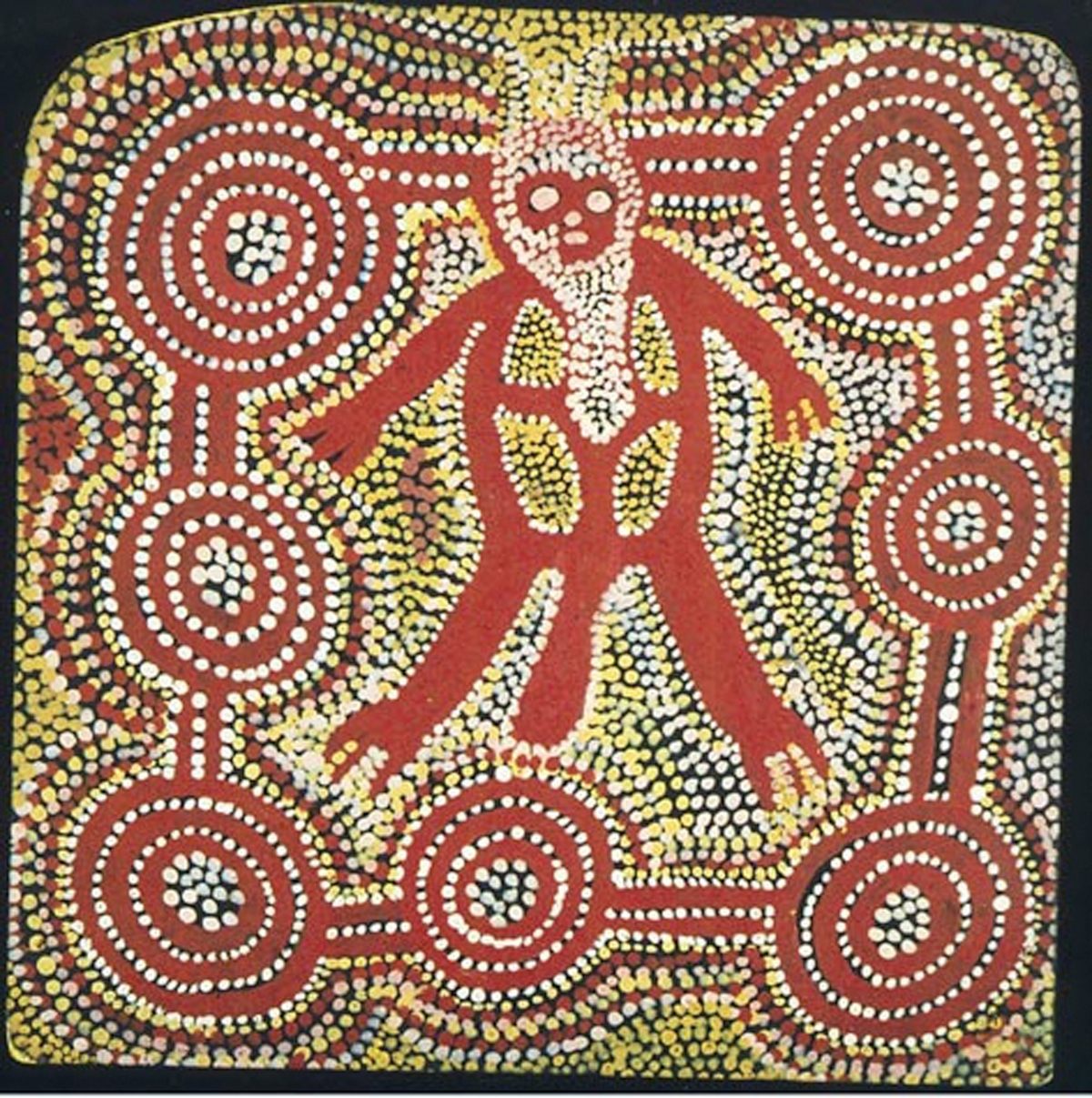

Monstrous beings are also depicted in many visual art traditions. Goya’s works of giants and child-eaters, including, for example, his gruesome rendition of Saturn devouring his own child, exemplify this. All cultures, it seems, have fairytales and narratives that express a high degree of aggression towards young children. There are many reasons for this, but ultimately it reflects the special vulnerability of the very young with respect to adults and the exterior world.

A terrifying pantheon of monstrous beings is one subject of visual artworks and traditional Aboriginal “Dreaming” narratives that merits inclusion in any typology of Aboriginal cultural and artistic traditions. All of these figures materialize fear, bringing it to the surface. At the psychological level, the stories about these entities are a means of coping with terror. To this I would add that such monstrous beings also attest to some of the least palatable aspects of human behavior, to the nastiest and most vicious of our human capabilities.

Importantly, in Aboriginal Australia, these figures and their attendant narratives provide a valuable source of knowledge about the hazards of specific places and environments. Most important of all is their social function in terms of engendering fear and caution in young children, commensurate with the very real environmental perils that they inevitably encounter.

The monstrousness of many, although not all, of these monstrous desert beings lies in their particular disposition towards cannibalism. In the farthest reaches of the Western Desert, in the Pilbara region, the brilliant although largely unheralded Martu artist and animator Yunkurra Billy Atkins creates extraordinarily graphic images of cannibal beings, including babies. These ancient, malevolent ngayurnangalku have sharp pointy teeth and curved, claw-like fingernails. They reside beneath a salt lake, Kumpupirntily (Lake Disappointment). In those environs they have been known to stalk and to feast on human prey—to be precise, Martu people.

Of Kumpupirntily, Australian National University researcher John Carty writes: “It is a stark, flat, and unforgiving expanse of blinding salt-lake surrounded by sand hills. Martu never set foot on the surface of the salt-lake and, when required to pass it by, can’t get away fast enough. This unnerving environment is grounded in an equally unnerving narrative. Kumpupirntily is home to the fearsome ngayurnangalku, ancestral cannibal beings who continue to live today beneath the vast salt-lake.”

And if that isn’t enough, malpu (devil-assassins) inhabit the same vicinity. As Billy Atkins noted in an oral history project: “It’s dangerous, that country. I’m telling you that that cannibal mob is out there and they are no good.”

The principal ngayurnangalku (meaning something along the lines of “they’ll eat me”) narrative centers on two distinct groups of ancestral people, one that wishes to maintain the ngayurnangalku practice of cannibalism, while the other contingent is vehemently opposed to it.

Martu man Jeffrey James, relating the narrative to John Carty, had this to say: “[One] night there was a baby born. They asked, ‘Are we going to stop eating the people?’ And they said, ‘Yes, we going to stop,’ and they asked the baby, newborn baby, and she said, ‘No.’ The little kid said, ‘No, we can still carry on and continue eating peoples,’ but this mob said, ‘No, we’re not going to.’”

There isn’t any evidence that the Martu people ever practiced cannibalism, but given the aridity and sparse distribution of vegetation and fauna on that very marginal and far-flung country, at times, in theory only of course, it must have been tempting. In this respect, monstrous figures reflect what could be described as the potential vulnerabilities and fault-lines of specific Aboriginal societies and locations. This is so the world over.

Traveling further east into Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (Anangu) country, but staying in the Western Desert, the fearsome mamu, also cannibals, hold sway.

With large protruding eyes, they’re sometimes bald and in some cases hirsute with long hair that stands upright. They’re equipped with sharp, fang-like teeth capable of stripping off their victims’ flesh. Dangerous shape-shifters, they are able to assume humanoid shape, but they’re also associated with sharp-beaked birds, dogs, and falling stars. The mamu, who also figure in Warlpiri and other desert groups’ narratives, typically reside underground, or live inside the hollow parts of trees.

The anthropologist Ute Eickelkamp has written persuasively about mamu from a largely psychoanalytic perspective, but also argues in a 2004 article that Western and Central Desert “adults commonly use the threat of demonic attacks [by mamu] to control the behavior of children.”

The belief system relating to mamu activity has extended into the post-contact lives of older Anangu people. This is demonstrated by the elderly Pitjantjatjara people who accounted for the mushroom cloud released by the 1956 British program of testing atomic bombs at Maralinga, on Anangu land, as evidence of mamu wrath and fury at being disturbed in their underground dwelling places and therefore rising up in a huge, angry dust cloud. Trevor Jamieson recounts his family’s experience of the Maralinga testing program in the theatrical work “Ngapartji Ngapartji.”

Among other sorcery figures that feature in Anangu Tjukurpa (“Dreamings”) is Wati Nyiru (“The Man Nyiru,” the Morning Star). Wati Nyiru chases the Kungkarangkalpa, the celestial star sisters comprising the constellation known to the ancient Greeks as the Pleiades, through the night sky, with sexual conquest (among other things) on his mind. The formidable artist Harry Tjutjuna, who paints at the Ninuku Arts Centre in northern South Australia, has become feted for his renditions of the Wati Nyiru and also for his barking spider Dreaming ancestor, Wanka.

Further north in Warlpiri country, the pangkarlangu is one of a number of frightening yapa-ngarnu (literally “human-eating” or “cannibal,” or more colloquially “people eater”) figures that recur in certain Warlpiri Jukurrpa (“Dreaming”) narratives. Pangkarlangu are huge, hairy, sharp-clawed, neckless baby-killers, physically described in similar terms to popular representations of Neanderthals or perhaps Denisovans (see the work of Adelaide University’s Alan Cooper, who has established Denisovan DNA in populations east of the Wallace Line).

The pangkarlangu’s physical attributes were first described to me in the early 1980s by a now-deceased Warlpiri woman who spoke little English, could neither read nor write and had never seen a visual representation of a Neanderthal, but her pencil drawing bore a striking resemblance to a Neanderthal.

The Warlpiri pangkarlangu, which extends further across the Central and Western Deserts, usually wears a woven hair-string belt around his middle. This accoutrement is closely connected to his foul purposes. Pangkarlangu, huge lumbering bestial humanoids, roam the desert in search of their desired quarry. In their spare time, they fight one another. They are classic representations of what has in recent years been described as “Otherness.”

Lost human babies or infants who’ve crawled or wandered away from the main camp are pangkarlangus’ preferred food source, being juicy, tender, and easy to catch. Pangkarlangu grab their prey by their little legs, upending them quickly, head down, tiny arms akimbo.

Warlpiri adults who are successful hunters use a similar technique to seize good-sized goannas or blue-tongue lizards by their tails, in order to prevent them from inflicting deep scratches or painful gashes on the arms or hands of their captors. The pangkarlangu models his baby-execution method on those human hunters of small game, killing the infants swiftly and expertly—by dashing their brains out on the hard red earth, in a single blow.

After slaying his defenseless victim, a pangkarlangu will string its little body around his waist, tying its legs onto his hairstring belt, so that its head dangles and bobs up and down as he strides along. The pangkarlangu will continue on his roving quest for more chubby little babies who’ve strayed from the care of adults, and goes on catching them until his hairstring belt is full, and he’s completely circled by lifeless dangling babes. Then the pangkarlangu makes a fire, chucking the dead tots onto the ashes, after which he settles down to gorge himself on a mouth-watering meal of slow-roast baby.

On one memorable occasion, in my presence, Lajamanu artist and storyteller extraordinaire Molly Tasman Napurrurla, in bloodcurdling language and with hair-raising vocalization (although if it were possible to appreciate the dark, gothic tenor of the situation, at another level it was hilarious, owing to the brilliant use of black humor in Napurrurla’s performance) described and mimed the actions of the pangkarlangu to an audience of deliciously terrified little children at the Lajamanu School.

Napurrurla re-enacted the pangkarlangu’s apelike ambulatory motion as it clumsily thumped around the desert, with the heads of little babies attached to his hair-string waistband bouncing up and down and swinging about when the large, ungainly creature changed direction.

There was no doubt in my mind that such narratives are first and foremost about social control with respect to the specific dangers of the desert where, in the summer months, people can die horribly tormented deaths from thirst within a matter of hours. Such monstrous beings and their attendant narratives exist to impress upon and to inculcate into young children the need for obedience to older members of the family, and especially not to wander off into the desert alone, lest they meet a fate perhaps worse than that of encountering a ravenous pangkarlangu.

Pangkarlangu, like other monstrous beings in Aboriginal Dreaming narratives, whether male or female, are more often than not depicted in figurative form (a rare occurrence in Central and Western Desert art, which is primarily iconographic) with grossly oversized genitals—their enormous members providing surefire evidence of malevolent intent.

Several years ago when I was negotiating with a publisher to write a children’s book about monsters in Aboriginal Dreaming narratives, all was going well until I showed him Pintupi artist Charlie Tjararu’s beautifully executed and evocative painting of a pangkarlangu. As I explained the significance of the figure’s monstrously-proportioned genitalia, the man turned to me and said: “But, ah, Christine, how are we going to explain the ‘third leg’ to the kiddies?”

As in the case of the desert regions, the repertoire of monstrous figures in Arnhem Land in the wet, tropical, monsoon-prone far north of Australia, speaks to the inherent dangers of particular environments. This is also reflected in artworks and narratives.

At one level, yawk yawks could be described as Antipodean mermaids—except for the fact that they are not benign. These fish-tailed maidens, young women spirit beings, with long flowing locks of hair comprised of green algae, live, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say “lurk,” in the deep waterholes, rockholes, and freshwater streams of Western Arnhem Land in particular.

Children and young people particularly fear them, because they are believed to be capable of dragging people underwater and drowning them. Like most Aboriginal spirits, they have the capacity to metamorphose, and can sometimes assume a presence on dry land, before morphing back into water spirits.

There are a number of celebrated artist-exponents of yawk yawks in Arnhem Land, including Luke Nganjmirra, a Kunwinjku painter working from Injalak Arts & Crafts, Maningrida-based brothers Owen Yalandja and Crusoe Kurddal (carvers), the sons of the late Kuninjku ceremonial leader Crusoe Kuningbal (1922-1984), and Anniebell Marrngamarrnga (a weaver who fashions yawk yawk maidens from pandanus) who also works with the Maningrida Arts and Cultural Center.

Also in Arnhem Land are namorroddo spirits. They have long claws and at night fly through the air, long hair streaming, to prey on human victims. Parents control children by cautioning them not to run around outside at night, particularly when there is a high wind, which echoes the sound that the namorroddos make as they whistle and swish though the night sky, their skeletal bodies held together only by thin strips of flesh.

Namorroddos are somewhat akin to vampires, in that they suck out their human victims’ life juices, after killing them first by sinking their long sharp claws into them. In turn, their victims are also transformed into namorroddos.

And sorcerers abound, none more feared than the dulklorrkelorrkeng, which are genderless (or rather, capable of assuming the characteristics of either gender), malignant spirit beings with faces similar to those of flying foxes; they eat poisonous snakes with relish to no ill effect.

Dulklorrkelorrkeng are known to go around with a whip snake tied to their thumbs, and they live in forests that have no ground water. In many respects they resemble the namande spirits of western Arnhem Land. The late Arnhem Land artist Lofty Bardayal Nadjamarrek, of the Kundedjinjenghmi people, was esteemed as possibly the greatest living limner of the sorcerer-spirit dulklorrkelorrkeng.

This account given here barely touches the surface of this vast topic. It points nevertheless to the extensive reach of Aboriginal Dreamings, culture, and visual art, which have the capacity to portray every aspect of human life, and the lives of other species too.

Ultimately, these monstrous beings and their narratives serve a critically important social function that contributes to the maintenance of life: that of instilling into young and old alike a healthy respect and commensurate fear of the specific dangers, both environmental and psychic, in particular places.

Christine Judith Nicholls is an honorary senior lecturer at Australian National University.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook