The Reluctant Saint Who Watches Over Senegal as Street Art

Amadou Bamba stood for freedom from imperialism, and now means much more.

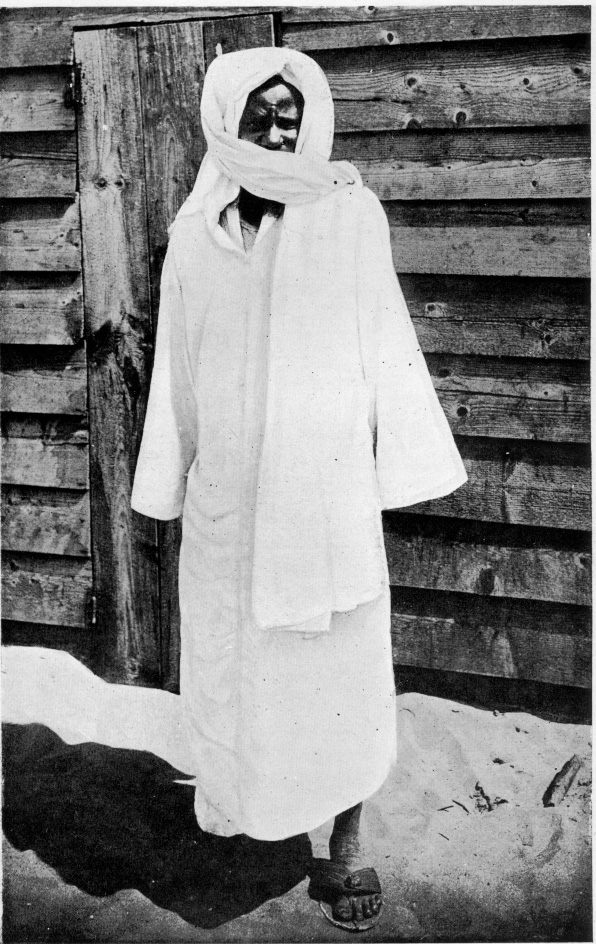

The photo was meant as a kind of a mug shot, so authorities could keep tabs on him. The photographer, a bureaucrat of the French colonial government in West Africa, aimed his camera at the standing Senegalese man, who was being kept under house arrest. The year was 1913 (or maybe 1914). Yet the camera did not capture a man trapped so much as a compelling, mythical radiance—the figure is poised, his headscarf glowing in blinding Sahelian sunlight, his face obscured but indelible. More than a century later the image has become unmistakable.

It’s the only known photograph of Sheikh Amadou Bamba (1854–1927), a spiritual leader of Senegal’s independence movement. Rendered variously in ink, paint, and charcoal, his image, based on that photograph, adorns homes and public spaces everywhere in the modern nation, from musician and politician Youssou N’Dour’s Dakar neighborhood of Médina to roadside villages in the interior. In murals, Bamba shares space with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., and his iconic outline festoons all forms of transport, from trucks and taxis to ships. All of these variations go back to that single, overexposed photo, and to the Mouride legacy that it unintentionally heralded.

In the late 1800s, the Mourides (meaning “disciple”) emerged as a peaceful resistance movement against French imperialism. Bamba, their leader, stood in a lineage of Sufi marabouts, or holy men, that dates back to 17th-century Morocco. He drew so many followers to his home in central Senegal that by 1891, French colonial officials grew worried about his influence. He preached submission to God and prized hard work as a source of maintaining dignity. His motto was: “Pray to God but plow your fields.” Some of his spiritual power and mystique, though, would later come from his reserved personality and the stories of hardships he endured at the hands of imperial powers.

Bamba was first imprisoned in 1895 on vague charges—authorities conceded in their own documents that they had “no clear instance of the preaching of holy war,” according to late University of London scholar of Islam in Africa, Donal Cruise O’Brien—and sentenced to exile. Following his arrest, he was taken to Saint Louis, the old port north of Dakar. When the captain of the French ship hauling him into exile in Gabon refused to allow Bamba to perform his prayers aboard ship, it is said, he threw his prayer mat overboard and prayed on the waves. That miracle of resistance is evoked throughout the harbor in Saint Louis today, where his shrouded image appears on the prows of fishing boats to protect crews going out to sea.

Sheikh Serigne, as he is widely known, became a West African saint for everyone, regardless of their beliefs. University of California, Los Angeles cultural historian Allen Roberts notes the irony around the 1913 photograph. A mug shot has a purpose—clear identification of its subject. “That’s what a mug shot is for,” he says. “This one is only recognizable by its enigmatic nature.”

Roberts and his wife, Mary Nooter Roberts, also a cultural historian at UCLA, were struck by the Bamba images they encountered in Dakar during visits in the 1990s, and collaborated with translator Ousmane Gueye to learn more. They covered the neighborhoods of Guel Tapée and Médina in late afternoons, looking for paintings. For the ones that they found, Gueye made preliminary surveys of a work’s history and then sought permission to photograph key paintings. When a homeowner learned why they were interested, invariably they would be invited inside, their hosts saying, “Well that one is okay, that’s outside. But come in.” Inside they would find an even richer variety. “A lot of people had commissioned artists or were artists themselves and would paint these environments,” Roberts says. In their bedrooms, people might cover the walls with the saint’s image to have its baraka, or blessing, during all waking and sleeping moments.

In that sense, the images bestow the saint’s active blessing, not just his memory, according to Mouride belief. As the Roberts note in a 2007 article in the journal Africa Today, the paintings are like visual forms of zikr, or devotional “songs of remembrance.” For Mourides, a follower is to “keep the image of his sheikh before his eyes for spiritual help” while reciting zikr.

A mural by a Dakar artist known as Papisto was a notable example. Papisto, who left school after third-grade, painted a 600-foot-long mural in the Belair neighborhood over several years in the 1990s, he told Roberts, to teach children in his informal settlement about important figures, from Malcolm X to Jimi Hendrix to Bob Marley. Creating environments in which Sheikh Serigne coexists with modern figures is important for both the communities and the artists, some of whom are unhoused. But Bamba was a centerpoint of the massive work, and it became a kind of shrine. Papisto traveled to Amsterdam in 2004 to take part in the Tropenmuseum’s Urban Islam exhibition. His last major work before his death in 2014 was a mural for the outer wall of the French Cultural Center of Dakar, commissioned in 2006, according to an obituary written by Roberts.

The project of documenting works inspired by Bamba took on a special dimension for the Roberts, a foundational effort that spanned two decades and resulted in an exhibition and publication, A Saint in the City (UCLA Fowler Museum), that tracked both their collaboration and their marriage. Mary passed away in 2018.

Bamba returned from Gabon in 1902, with a pardon. Back in Senegal, his popularity only grew. Within two years he was sentenced again, this time sent to a desert encampment in Mauritania, where he remained for four years. In 1907 he returned again, and was placed under house detention—the circumstances under which the famed photo was taken. Having taught himself Arabic, Bamba wrote thousands of lines of poetry and prose, devotional passages that place him firmly in the Sufi tradition. He believed his writings could help move Senegal toward a purer form of Islam, according to the writings of O’Brien. He remained a quiet personality who resented the crowds who sought him out, but he endorsed the activism of his followers without actively proselytizing himself. This personal reticence added to his mystique.

The photo of Bamba was published in 1917 by the photographer, Paul Marty, in the first volume of his monograph Studies on the Islam of Senegal. The volume became a “classic,” prized by generations of colonial administrators. Ironically, copies of this book, which played an important role in shaping the colonists’ response to African Islam, also played a key role in disseminating the saint’s image among the faithful.

Senegal achieved independence in 1960, but few if any records note when the paintings of Bamba’s image first began to appear on walls. “I’m not sure if such histories can be reconstructed,” writes Roberts, but he speculates that the spread of the images in working-class neighborhoods of Dakar from the late 1980s was influenced by national politics. In 1988, then-president Abdou Diouf imprisoned his rival Abdoulaye Wade, who was a devoted Mouride. Roberts says that opposition to Diouf and support for Wade, who succeeded Diouf as president, helped make Bamba’s blessing more visible and public.

Bamba was buried in the Great Mosque of Touba, in central Senegal. Millions make a pilgrimage there every year. Senegal’s some four million Mourides today include members of the Baye Fall movement, named for Bamba’s disciple Ibrahima Fall, among them popular musicians such as N’Dour and Cheikh Lô. The Senegalese diaspora has taken his legacy abroad; New York and other cities celebrate Amadou Bamba Day each July 28, and his famed image comes out in force.

Among the more prolific artists the Roberts encountered in the course of his research was a Dakar painter named Pape Diop. They tried to locate him early in the 2000s without luck, as he had no fixed address. Recently, curators from Yataal Art studio in Dakar have traced the work of street artists, including Diop. Curator Mamadou Boye Diallo featured his work in two exhibitions. The first, in 2018, was an “underground” exhibit across the streets and old houses of Médina.

A year later a more formal exhibition, Hors norme, took shape at the Pavilion de l’Institut Français. “Pape Diop came the day after the opening at the Institut to see the exhibition,” says Diallo, and was pleased to see his works displayed, but the surroundings were uncomfortable for him. “It didn’t seem convenient to bring him to this place when there were so many people well-dressed,” says Diallo, “while he didn’t have shoes.”

The contrast between the two exhibitions highlights the chasm between art worlds. “That’s also the meaning of the title of the exhibition, Hors norme [akin to Non-standard],” says Diallo. Hors norme refers to the artist, the works themselves, and the bridge they create between modern Dakar and its traditions.

The city’s Museum of Black Civilizations has a life-size display of Bamba’s photo illuminated behind glass, confirming his place in West African life and culture. It also affirms how his imagery has permeated, from grassroots to high culture.

“Bamba is the ocean,” goes a Wolof saying, a sea of wisdom available to all.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook