An Abridged History of Funambulists

Con Colleano on a slack-wire, circa 1920 (image via Wikimedia)

This past Sunday, Nik Wallenda, a seventh-generation aerialist and member of the Flying Wallenda circus family, walked 94 feet on a tightrope between two Chicago skyscrapers. He was blindfolded, 600 feet in the air. The stunt was broadcast live — but with a 10 second delay, in case he fell. He didn’t, of course, and the jaunt added two new Guinness World Records to the nine he already holds.

The Wallendas are among the most high-profile acrobats today, and they’re part of a long tradition of highwire daredevils. Here’s an abridged history of tightrope walkers, who have managed to put the “fun” in funambulist for thousands of years.

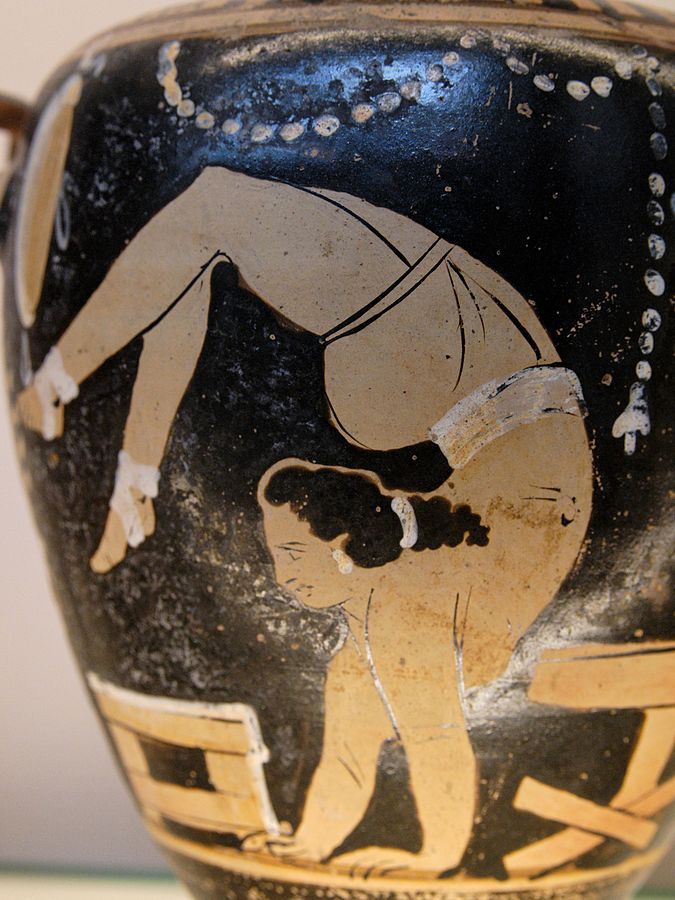

Funambulism dates back at least to Ancient Greece — that’s where the name comes from: funis means “rope” and ambulare means “to walk.” In both Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, tightrope walkers were revered, but their work was not considered “sporting” enough to be part of the Olympic Games. Instead it often became the providence of jesters and other entertainers.

Female acrobat on an Ancient Greek hydria (image from the Townley Collection via Wikimedia)

Female acrobat on an Ancient Greek hydria (image from the Townley Collection via Wikimedia)

Rope-walkers lost some ground in 5th-century France; they were forbidden to come near churches, and since near churches was where most of the fairs were held, this was effectively a ban on tightrope-walking. But things seem to have got back on track by the 1300s; during the lavish coronation of Queen Isabeau in 1389 Paris, an acrobat carrying candles “walked along a rope suspended from the spires of the cathedral to the tallest house in the city.” This trend continued; there were tightrope walkers at the coronation of Edward VI in Westminster in 1547, and at the occasion of Philip of Spain’s arrival in London to meet Queen Mary in 1554. In Venice in the mid-16th century, the annual Carnival gained a new opening tradition — Svolo del Turco (Flight of the Angel) — when a Turkish acrobat walked on a rope strung between the bell tower of the St. Mark’s Church and a boat docked on the Piazzetta. During the late 1600s in England, tightrope walkers began to be associated with a disreputable element, including pickpockets, streetwalkers, and conmen. In his early-1700s song collection “Pills to Purge Melancholy,” Thomas D’Urfey wrote: “In houses of boards men walk upon cords / An easy as squirrels crack filbords / The cut-purses they do bite, and rob away.”

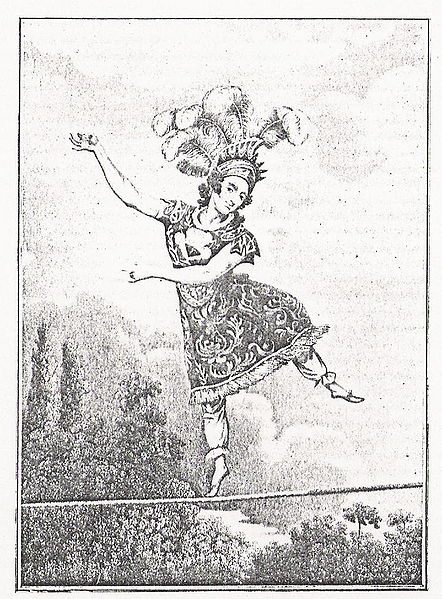

One of the most famous funambulists of the late 1700s was Madame Saqui. She performed many times for Napoleon Bonaparte, often walking a wire with fireworks exploding all around her, and also at the celebration of the birth of his heir by walking between the towers of the Notre-Dame cathedral. She also performed at Vauxhall Gardens and is mentioned in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair; she ran her own circus theater for some time and continued to perform well into her 70s.

Madame Saqui (image via Wikimedia)

Madame Saqui (image via Wikimedia)

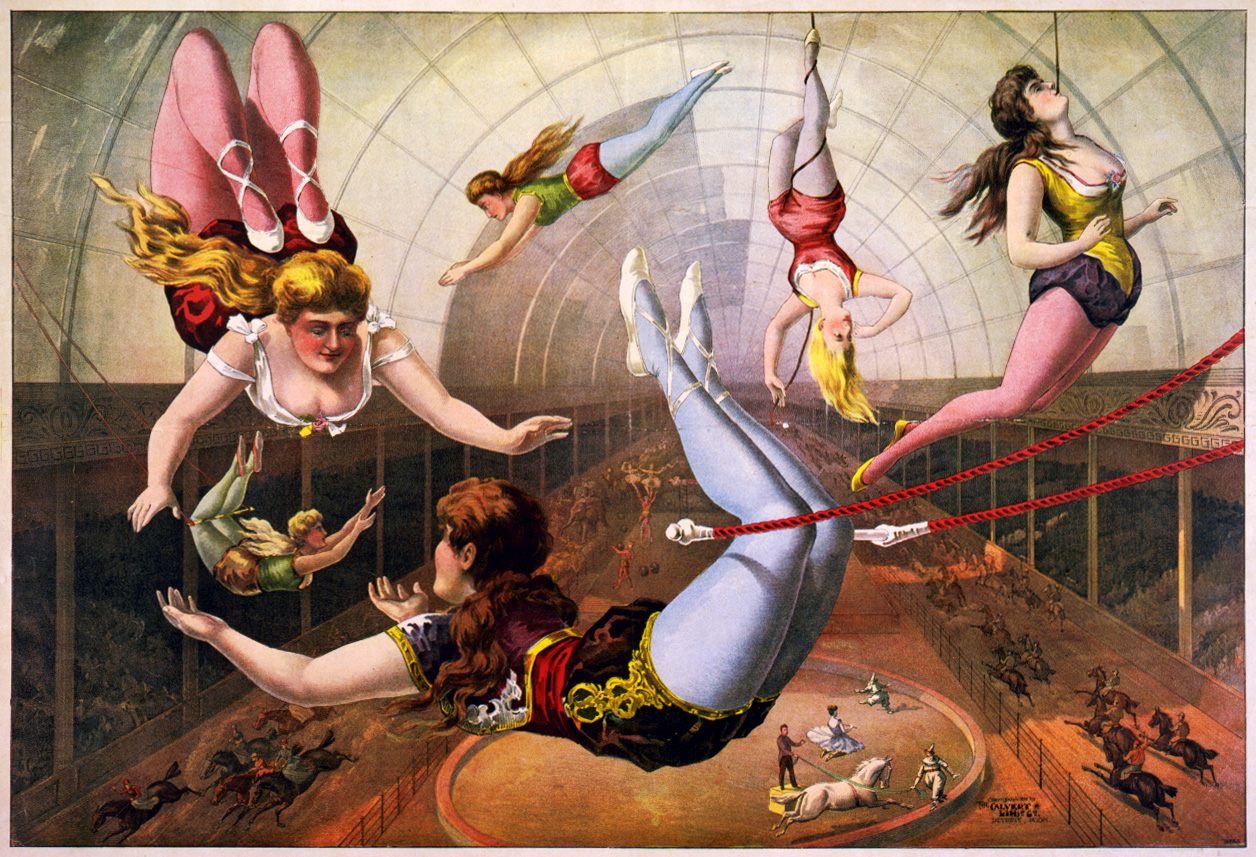

The 1800s brought acrobats and other similar performers indoors as business- and showmen opened more permanent circus venues. Pablo Fanque was the first nonwhite circus proprietor in Victorian Britain, and he began his performance career doing equestrian stunts and rope walking. He started the Pablo Fanque’s Circus Royal, in which he continued to perform; it quickly became the most popular circus in the area, and remained so for 30 years. Fanque toured all around the UK for years and also held many circus benefits — one of which, for circus performer William Kite, inspired the Beatles song “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite.”

“Trapeze Artists in Circus” by the Calvert Litho. Co., 1890 (image via Wikimedia)

“Trapeze Artists in Circus” by the Calvert Litho. Co., 1890 (image via Wikimedia)

In the 1800s everyone wanted to walk across Niagara Falls. The first to do so was Jean François Gravelet, known as the Great Blondin, who was the most famous wire-walker of the time. He crossed the Falls in 1859, pausing in the middle to sit down and drink a beer he pulled up on a rope from the Maid of the Mist. He would return to the Falls again and again, doing crazier highwire stunts each time: riding a bicycle across, cooking an omelet in the middle, going across blindfolded or on stilts, and even carrying his manager across on his back. Next up was the Great Farini (né William Leonard Hunt), one of the most celebrated acrobats in Europe at the time. He duplicated many of the Great Blondin’s stunts, and his coup de grâce in 1860 was crossing the Falls with a washing machine strapped to his back; in the middle he stopped to wash several handkerchiefs, which he then gave to his waiting admirers. Maria Spelterini, a circus performer from the age of 3, was the first woman to wire-walk across the Falls, and she also did it many times — once with her wrists and ankles manacled, once with a paper bag over her head, and once with peach baskets on her feet.

Maria Spelterini walking over Niagara Falls (image from George E. Curtis via Wikimedia)

Funambulists continue to devise more dangerous and incredible tricks. Ivy Baldwin, an experienced daredevil balloonist, spent years entertaining guests at the Eldorado Springs Resort near Boulder by walking across Eldorado Canyon numerous times, including his last, in 1948, on the occasion of his 88th birthday. The modern incarnation of the Flying Wallendas began around that time, debuting their most famous stunt, the seven-person chair pyramid, in 1947. In 1974, Philippe Petit walked a high-wire between New York’s World Trade Towers, and in 1989 he walked an inclined wire strung up to the second level of the Eiffel Tower. In 2009 Eskil Rønningsbakken, an “extreme artist,” rode a bicycle upside-down across a wire over a fjord in Norway; he has also walked on a tightrope strung between two hot-air balloons. Adili Wuxor, China’s “prince of the tightrope,” set a Guinness World Record in 2010 after he walked on a rope for just shy of 200 hours over a period of 60 days, and in 2013 he walked 500 meters across the Pearl River in Guangdong.

The Flying Wallendas seven-person pyramid (image from Porterlu via Wikimedia)

The Flying Wallendas seven-person pyramid (image from Porterlu via Wikimedia)

From shunned jesters to revered World Record holders — the position of funambulists in society has evolved alongside the increasingly daring tricks of the trade. For a far more elaborate history of the art, check out “Funambulus / Funambule: Rope Walkers & Equilibrists“ at the Blondin Memorial Society, which is itself adapted from The Tightrope Walker by funambulist Hermine Demoriane.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook