The Twilight of the Analog Photo Booth

The effort to save a rare beast on the road to extinction.

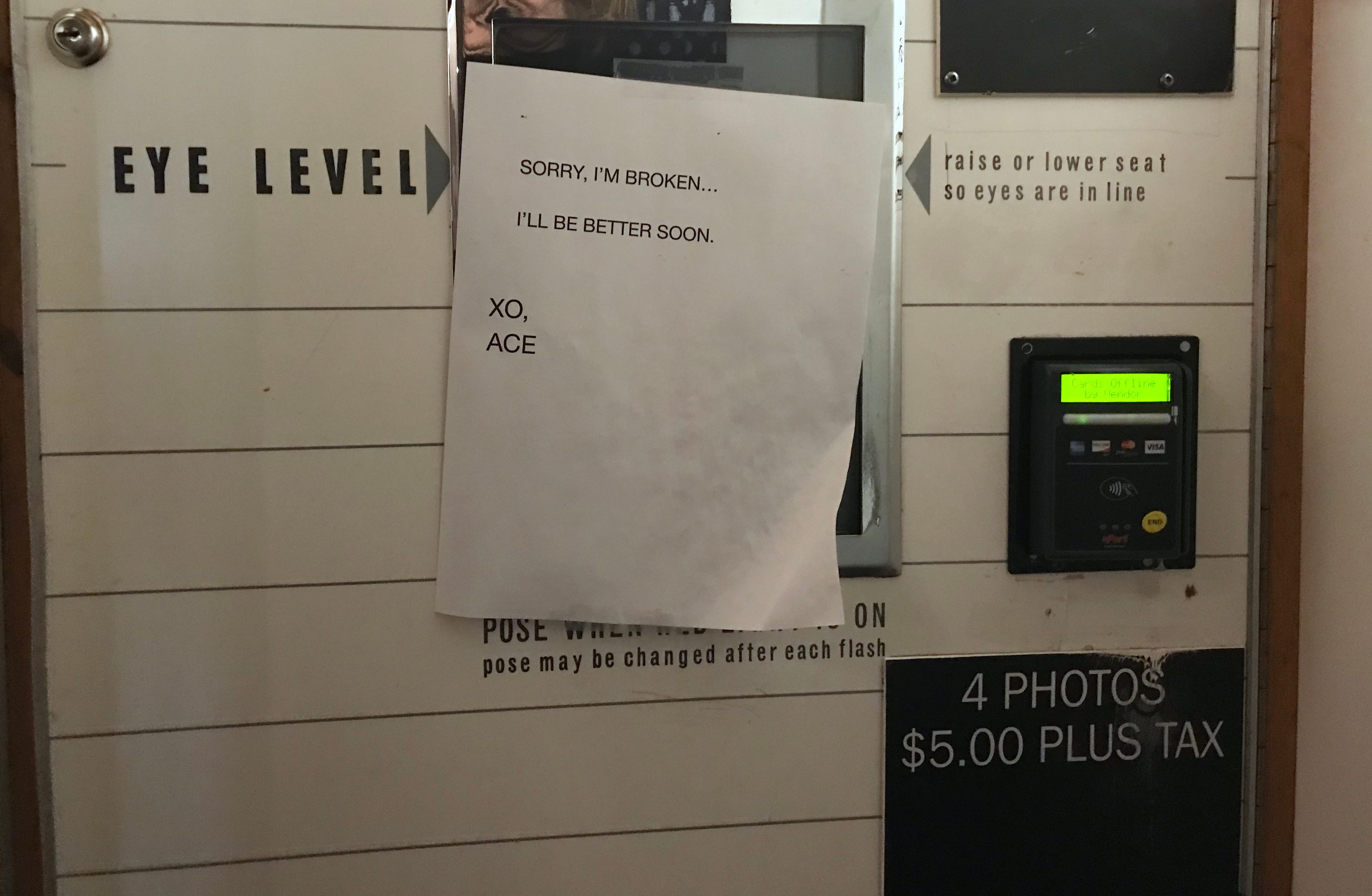

On a recent Saturday morning in New York, the analog photo booth in the Ace Hotel on 29th Street was out of order. Inside the booth, which costs $5 plus tax for a strip of four black-and-white photographs (cards accepted), a piece of paper hung askew atop the mirror, level with the sign reading “EYE LEVEL.” “Sorry, I’m broken …” it read. “I’ll be better soon. XO, Ace.” Barely a dozen of these film-based photo booths remain in the city, a fact that would have been inconceivable as recently as the 1990s.

In September 1925, the crowds stretched around the block for the first ever Photomaton studio, 30 blocks north of the present site of the Ace Hotel, at 51st Street and Broadway. Each subject paid 25 cents, was bathed in flashes of light, and waited eight minutes for a strip of eight photographs. Eighteen months later, the New York Times reported, “Young Photomaton Inventor Will Celebrate His First Million.” In today’s money, this would be close to $14 million.

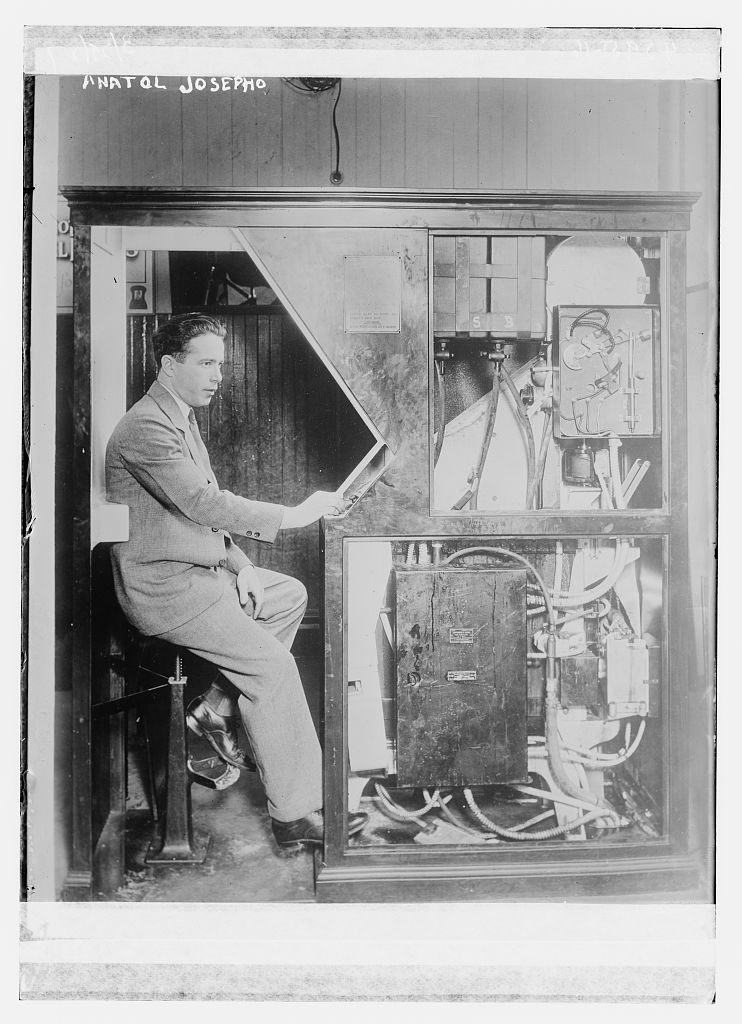

The inventor, Anatol Josepho, was born in 1894, and came from nothing. Josepho, né Josephowitz, grew up a banished Jew in Siberia. At 15, he went off to explore the world, starting in Berlin, where he bought a Brownie camera and learned to take photographs. Later, he took it to Budapest, to Shanghai, and eventually to New York. In Harlem, in 1925, he raised the $11,000 required to build a prototype for the first curtain-enclosed photo booth—the cost of nearly six reasonably sized houses at that time. Josepho was charming, and obsessed with the project, writes photographer Näkki Goranin. Despite being a newcomer to the city, “[he] was able to talk people into loaning him the money, find the appropriate machinists and engineers to help him build his Photomaton machine, and be sought out by the leading industrialists in America.”

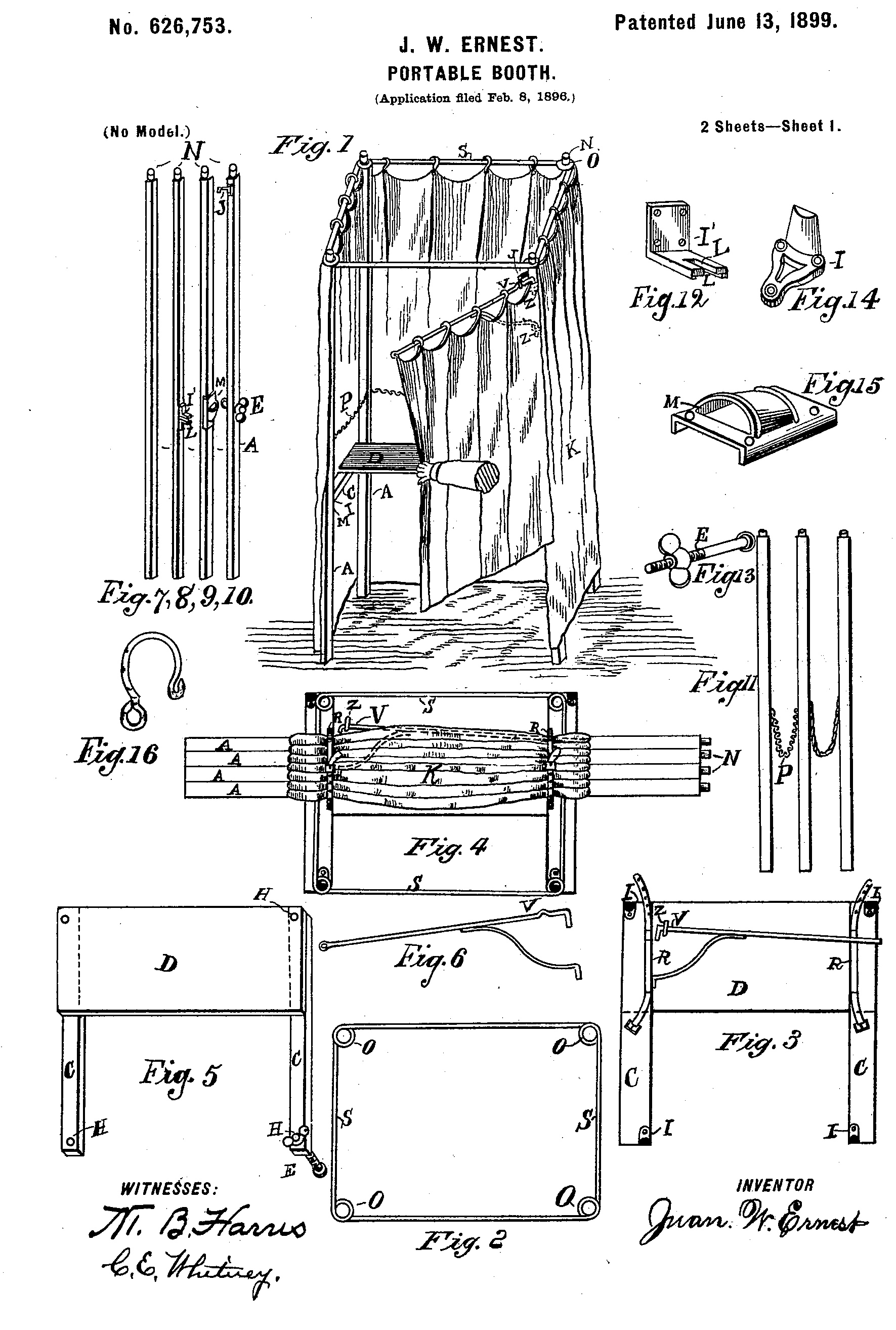

Josepho stood on the shoulders of decades of tinkerers who had been flirting with this technology since the 1880s, when a craze for vending machines of all kinds, including seltzer, chocolate, and postcards, seized Europe and America. Concurrently, photographic technology was developing at a galloping pace. Some early booths offered prints for a penny, others unreliable tintypes with near-unrecognizable subjects. Throughout the 1920s, the technology was becoming more and more refined—until, in 1925, Josepho patented the booth that set the standard for the next 90 years.

Before long the photo booth was everywhere: malls, bars, airports, post offices, Fred Astaire films. In the United States, they were often owned by the company PhotoMe, says Tim Garrett, an artist who co-runs the site Photobooth.Net with friend and colleague Brian Meacham. “It wasn’t a bunch of hipsters, it was a bunch of old-time vending guys,” he says. He adopts an accent. “Like—‘train stations are good,’ ‘bus stations are good.’” Couples enjoyed illicit kisses inside (sometimes, as a result, curtains were removed), friends posed together, and artists worked them into their oeuvre. It was a simple process. You went in, sat on the adjustable stool, lined up your face, and mugged for four flashes and shutter clicks. Then came the interminable, endless wait, of about three or four minutes. Underneath the glossy exterior, a furiously complicated contraption was whizzing and whirring—springs and arms and whirligigs, what photo-booth enthusiasts refer to as tubs of “chemistry,” strips of specially treated paper. Finally, your photographs were spat out, still wet, from the slot on the side. If you lost them or hated them, too bad. No negatives, no previews, no do-overs. But you did get four.

Even the youngest analog booths you see around today, says Garrett, were manufactured in the late 1960s and early 1970s. “The photo-booth companies stopped manufacturing them from scratch. They would pull the old machines, re-skin them, and then put them back out as new machines, when it was still the same chemistry inside.” The color machines that came later didn’t require different mechanisms or booths—just different chemicals (both powder and liquid). And it wasn’t a stretch to update them with new signage, lights, or innovations such as card readers. “At some point, the booths reached a critical mass, and then they didn’t have any reason to manufacture them.”

But two technological developments spelled doom for the old chemical booths. First, the advent of Polaroid photography, which made immediate photo gratification easier and more flexible. Next, in the 1990s, came lightweight digital color photo booths. These were cheaper, faster, and more easily moved, and required much less maintenance. Slowly, then quickly, chemical booths were phased out. Garrett and Meacham began running their user-generated site in 2005, which calls for film and photo-booth nuts around the world to map the devices wherever they find them. “When Brian and I started tracking stuff, it was just at the end of what might be called the centralized photo-booth operation,” Garrett says. PhotoMe owned virtually every booth in the country, and hired local people to maintain them and collect the money from their coffers. They eventually pulled the chemical booths and started switching to all-digital models. “Like, photo kiosks, at the beginning of the digital camera,” Garrett says, “where you could print your photos there.” In many cases, they didn’t bother to replace them at all.

Today, the chemical photo booth seems analogous to the giant panda: hefty, black and white, rarely seen in the wild.

Few people know how to care for them properly, and moving them from place to place is a major operation, in which a slight jolt could damage them in any number of ways. And the chemistry and paper are specific, expensive, and rare. Ninety percent of the population doesn’t care about, or notice, the difference between analog and digital booths, Garrett says. But for those who do, “digital just doesn’t capture it.”

Enthusiasts may buy an old booth, refurbish it, and then rent it out for weddings or to bars. Garrett estimates that fewer than 10 people across the United States know enough about them to do a full, top-to-bottom rebuild, though there are many more who know enough to at least maintain them. Still more could, relatively easily, be shown the ropes, he thinks. Even so, it’s not a guaranteed money-maker. In addition to the regular maintenance and topping up of chemistry and paper, things often go south with the old, finicky machines. For a while, he trucked an old booth around the country for events himself. “If it’s a wedding, it’s kind of a make-or-break deal. It’s hard to justify. It’s just a riskier operation than throwing out a digital booth.”

Nonetheless, people and the booths they love and tend to persist. Each of the nine Ace Hotel locations around the country has its own booth in the lobby. In New York, they can be found at trendy, dive-y bars such as Otto’s Shrunken Head, Bushwick Country Club, and Union Pool. The $5 strips of pictures often get rephotographed on a phone and Instagrammed out to the world. In Europe, and especially in Berlin, analog booths are flourishing all around the city.

“Unless there are people actively destroying them, there are going to be analog photo booths for years to come,” says Garrett. “There are enough of them out there that I don’t think their existence in private hands is really under threat.” Like used cars, some are in better nick than others, though tender loving care should help them run for years to come, assuming they garner enough interest. But the machinery is just one part of the puzzle. They also rely on chemistry, paper, and manpower.

Garrett and Meacham have run through chemistry company after chemistry company. The chemicals needed are well known, they say, and don’t require any technical knowhow to make—just the will to actually prepare them. Most recently, they used a supplier in Missouri, who sold out to a bigger company. “It was just a guy in a ten-sided building in the hills of the Ozarks, mixing this chemistry and shipping it all over the world,” Garrett says. The margins aren’t huge, but there’s reason to believe these substances will be available for some time. Paper, on the other hand, is tougher. The Russian company Slavich is the world’s only producer of analog photo-booth paper, a side operation alongside lead glass for X-ray facilities and other specialist supplies. Increasingly, even their main trade has been curtailed by the rise of digital imaging. If they folded, or stopped producing the very specific paper, photo booths around the world would have just their leftover stock—and then, finito.

Finally, there’s the question of manpower. On that Saturday morning in New York, a beardy technician—who didn’t want to give his name—in a black T-shirt with a large doctor’s bag came in to mend the Ace Hotel photo booth. This is a side gig for him, he says. He picked up the trade not as a photo-booth enthusiast, but back in the 1990s, when he worked at an arcade that had one. As analog photo booths “in the wild” are moving into the realm of distant memory, people who picked up the skills in the course of an ordinary job will move on to other things by necessity. At that point, the upkeep of these decades-old, thousand-pound booths will exclusively become the preserve of aficionados, the dedicated nostalgists. All that, just to capture the feel of damp photo paper and the unexplainable photographic quality that the digital booths will never replicate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook