Anthropomorphic Taxidermy: How Dead Rodents Became the Darlings of the Victorian Elite

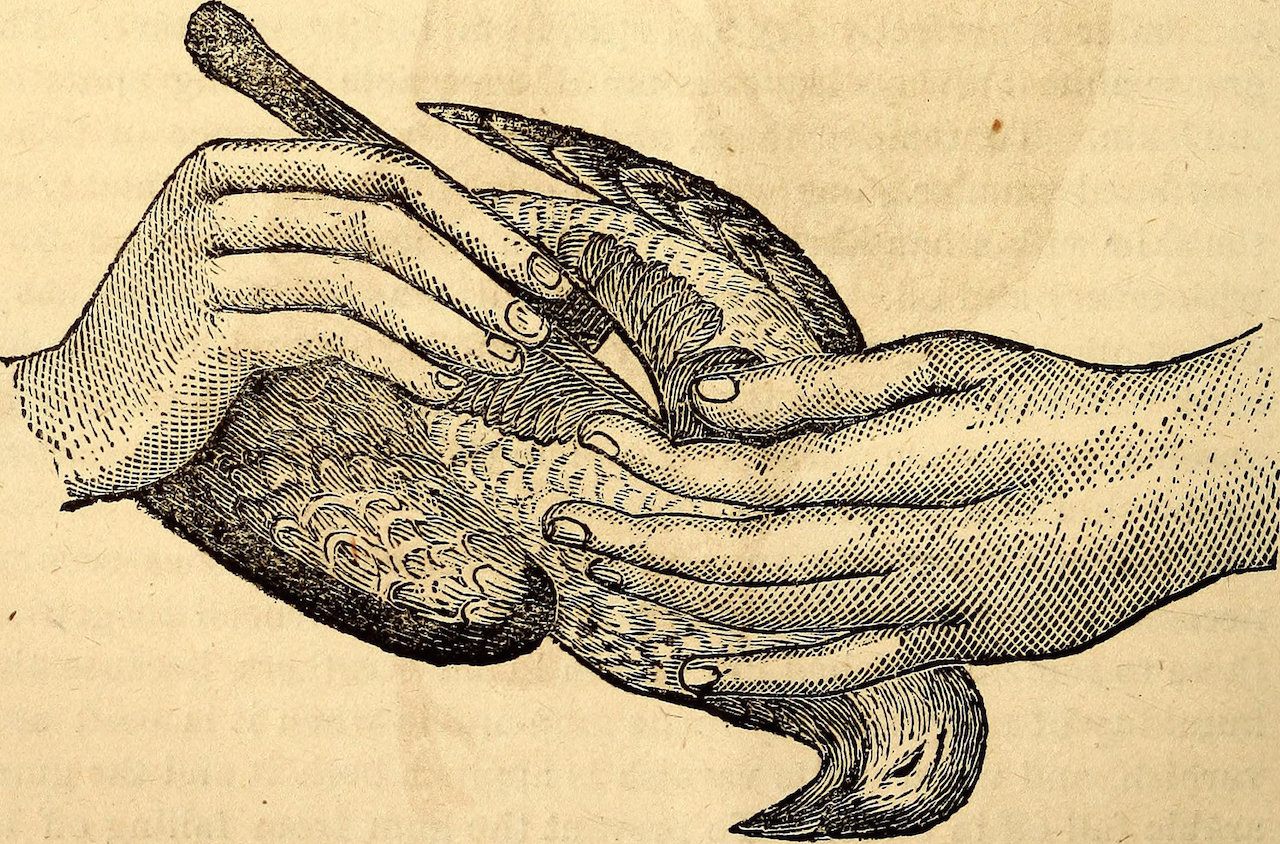

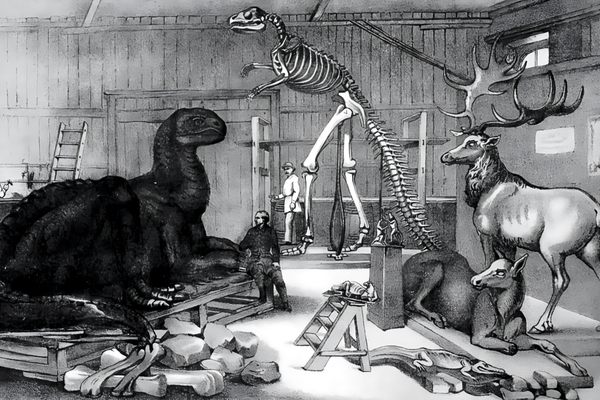

Illustration from “The Taxidermist’s Guide” (1870) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Illustration from “The Taxidermist’s Guide” (1870) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Dead kittens sharing tea and crumpets. Dead hamsters playing cricket. Dead rabbits cheating on a math quiz. How did these scenes of morbid yet comical magic come to pass? It was a marriage of fact and fancy: the Victorian passions for whimsical fantasy and natural history came together in one irresistible art form: anthropomorphic taxidermy.

Death and mourning possessed the Victorians, a society inextricably linked to their loyalty to the past. The rituals of expressing grief adhered to stringent rules that were often implemented on an outlandish scale. After Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria’s period of mourning, which continued until her own death, inspired a whole wave of artistic influence. From electroplating the dead to crafting ornaments from their body parts, Victorians commemorated their loved ones with post-mortem mementos that seem gruesome or downright perverse to our sensitive modern culture.

The practice of taxidermy allowed people to honor their precious pets by stuffing and mounting them for eternity. Preserving dead animals also satisfied scientific curiosity, as well as the desire for protected beauty.

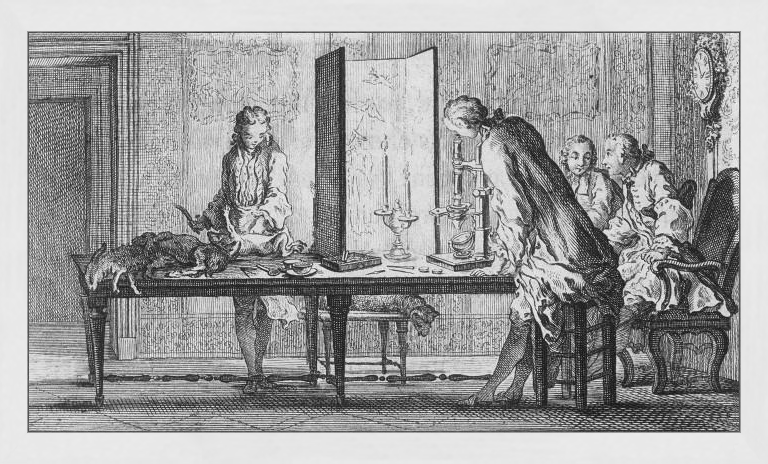

Early dissection & preservation techniques from ‘L’Histoire des Animaux - Zoology’ (via Gallica Digital Library)

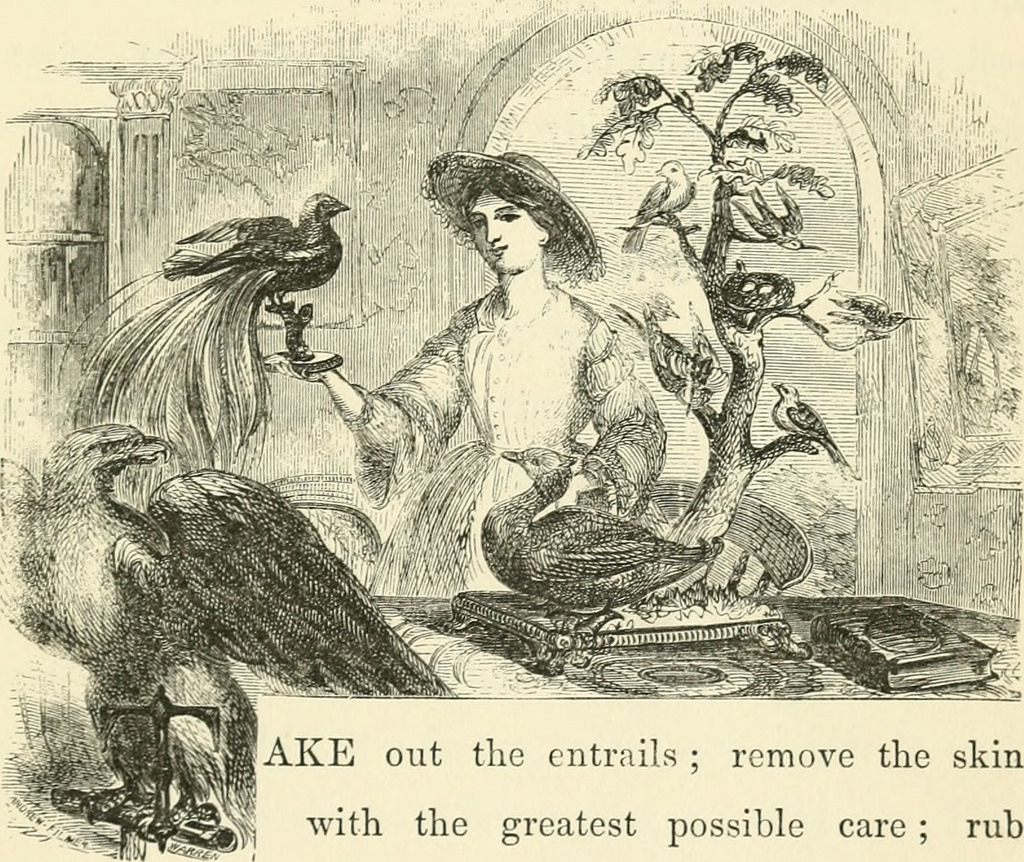

“Take out the entrails; remove the skin with the greatest possible care…,” an illustration from an 1871 crafting publication (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Following the Age of Enlightenment’s scientific boom, natural history was an immensely prevalent interest for the upper classes as well as politically. In the 18th century, the European pioneers of taxidermy used rudimentary formulas to preserve birds for scientific study. Over the next century, taxidermists invented more non-poisonous preservation methods, but the work still lacked artistry, as the specimens retained their stiff little corpselike demeanors.

Crystal Palace from the northeast from ‘Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851’ (via Wikimedia)

In the 19th century, drastic scientific and technological changes, not to mention evolutionary thought, meant that divine beliefs yielded to fixations on nature, life, and death. The technological advances of the age were showcased in the first world’s fair. The Great Exhibition, also called the Crystal Palace Exhibition, was housed in Hyde Park, London in 1851, headed up by Henry Cole and Prince Albert, consort to Queen Victoria.

The majestic Crystal Palace, designed by greenhouse engineer to the stars, Sir Joseph Paxton, was a technologically innovative acropolis of iron and glass, the construction of which was made possible by very recent inventions, such as industrial steam engines and electric telegraphs. The exhibition housed 14,000 exhibitors and provided a platform for all nations to flaunt their industrial progress. But the show clearly acted as a public relations device to boost the image of British superiority, which certainly helped secure Prince Albert’s reputation.

Crystal Palace steel engraving of interior during the Great Exhibition (via Wellcome Images)

The exhibit that absolutely enraptured the Victorians was the anthropomorphic taxidermy tableaux created by Hermann Ploucquet (1816-1878), German taxidermist for the Royal Museum in Stuttgart, whose commercial success vitalized his pursuit toward more artistic and natural techniques.

His inventive methods were hewn from an informed scientific mind with a desire to be a fine artist. Each diorama invited the viewer into a miniaturized world, intensified with concentrated emotions, somehow contained and accessible to the curious human gaze.

Ploucquet’s work dazzled Victoria and Albert, as well as Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, Lewis Carroll, Charlotte Bronte, and six million other attendees. Though some of his gory displays incurred critics’ contempt, Ploucquet had his finger on the pulse of the art crowd, creating dioramas that mimicked the style of the fashionable paintings and sculptures of the day. The Victorians found the tableaux unequivocally beguiling, and Queen Victoria described them in her diary as “really marvelous.”

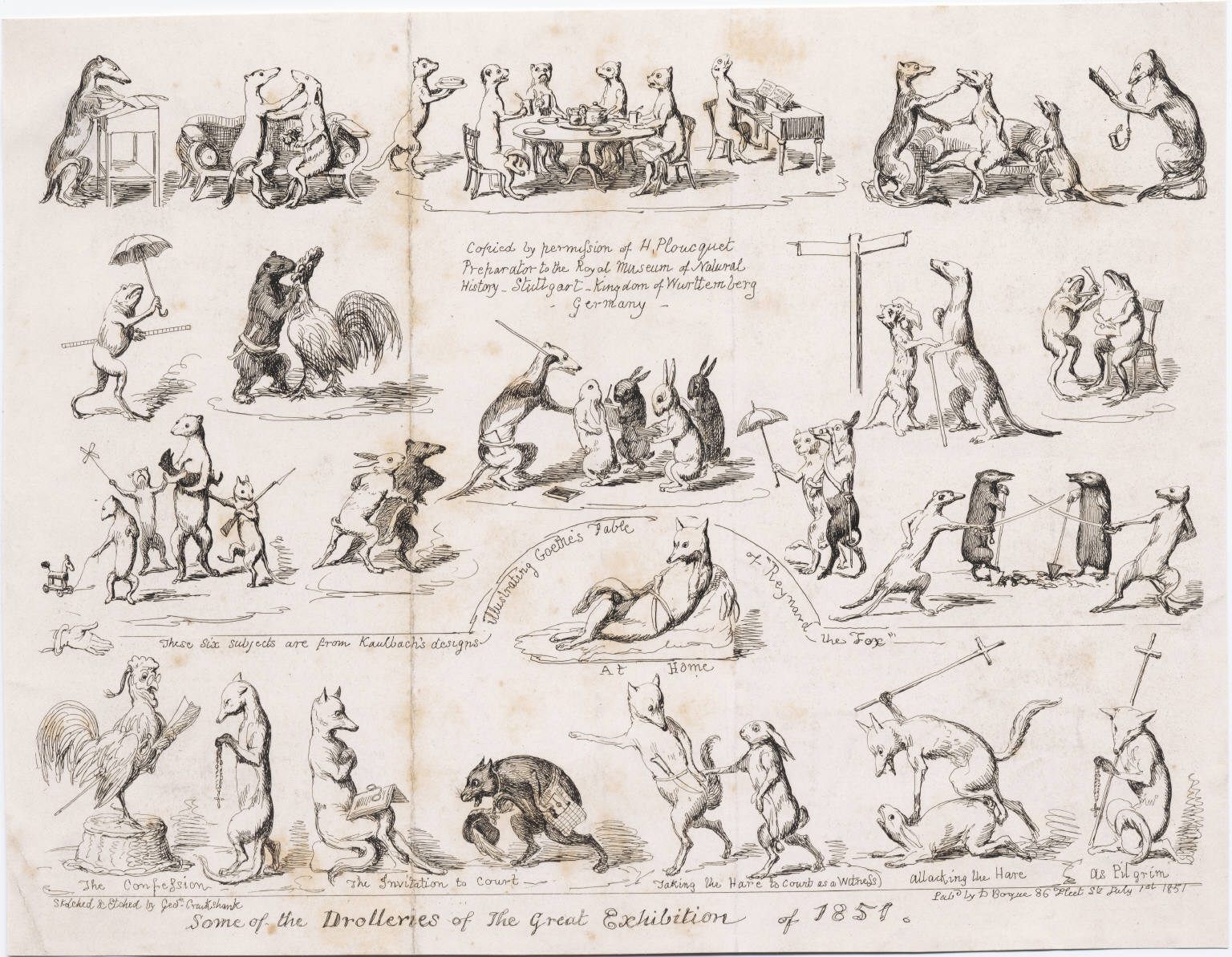

Etching from sketches by George Cruikshank of Hermann Ploucquet’s “drolleries” in the Great Exhibition of 1851 (via LWL Digital Collections)

1851 photograph of one of Hermann Ploucquet’s dioramas (via Pat Morris/University of the West England)

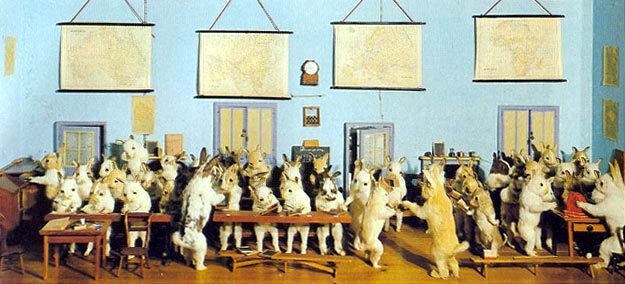

The fantastical allegorical scenes served to humanize the animals and animalize the human spectators in a delicious hybrid of delight and shame. The little landscapes of critters frozen in the midst of human activities were originally known as grotesques. Ploucquet took the art form to the next level with his dramatic tableaux, including scenes of kittens serenading a piglet, a weasel disciplining a classroom of rabbits, dueling dormice, ice skating hedgehogs, and action scenes portraying Reineke, or Reynard the Fox, a medieval European folk tale made famous by Goethe.

His stuffed animal tableaux were recreated in a book of woodcut illustrations — The Comical Creatures from Wurtemberg — published soon after the exhibition. Ploucquet went on to open a private museum filled with wall-to-wall lifelike animal montages.

Walter Potter’s “Rabbit School” diorama (via Wikimedia)

Walter Potter (1835-1918), an English inn keeper’s son and possibly the most widely known anthropomorphic taxidermist, went from preserving his own dead birds to creating an unparalleled collection of thousands of stuffed beasts donning human clothing. Potter is believed to have used only previously deceased animals in his creations, donated by a local farm. Ploucquet may have inspired his work, but Potter was a self-taught amateur. He created his art for the purpose enjoyment, based on fantasy and fairy tale rather than technical accuracy and character allegory.

At 19, Potter spent seven years creating his masterpiece, “The Death and Burial of Cock Robin,” which showcased 98 species of birds. In 1861, he opened his private museum in Bramber, Sussex, displaying his intricate dioramas, including a kitten wedding party and a rats’ den being raided by the police. Even the dangerous scenes retained their tenderness and humility. Where Potter lacked in anatomical precision, he dominated in unrivaled detail, from the kittens’ jewelry and frilly knickers to the squirrels’ fancy little brandy decanters.

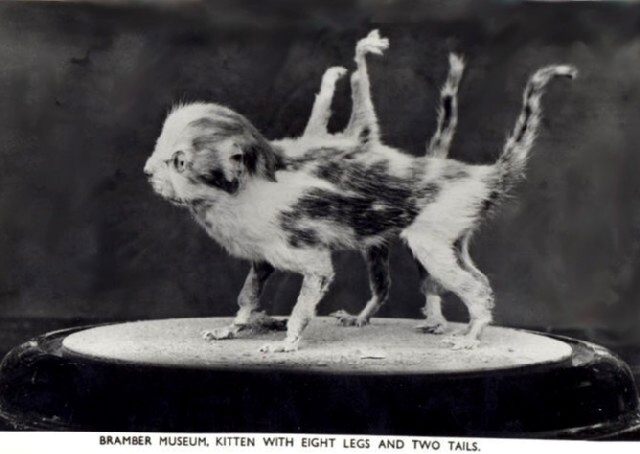

Rife with affable waggishness, Potter’s tableaux escalated the heights of peculiarity even further with his genetic mutations, such as eight-legged kittens and two-headed lambs. By the end of his life, Potter’s museum held a collection of 10,000 specimens, which remained intact under various ownership until Walter Potter’s Museum of Curiosities was auctioned off in 2003 at the Jamaica Inn in Cornwall for over £500,000.

All the more to love! Walter Potter’s eight-legged kitten (via Wikimedia)

Ploucquet and Potter gratified the Victorian passion for nature in its anti-naturalistic form. They harnessed a wild bestial power and made it into a kitschy commodity, where whimsy overpowered the morbidity of the situation.

Although Potter’s work has been disseminated into 691 different lots, parts of the collection have been shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Liverpool Museum, and Sir Peter Blake’s exhibition at the London Museum of Everything.

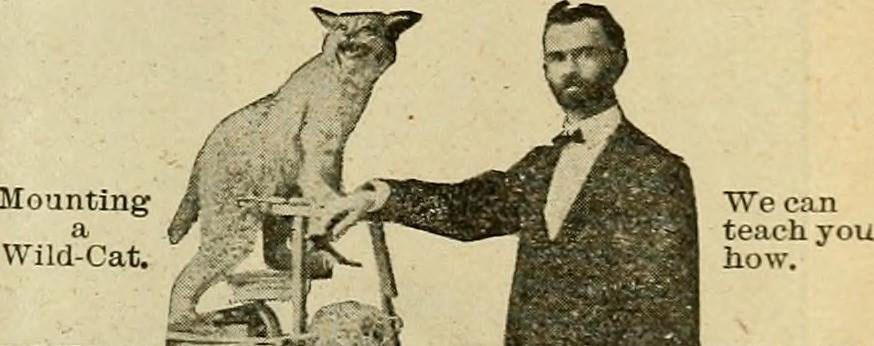

Learn taxidermy by mail advertisement from 1886 (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Learn taxidermy by mail advertisement from 1886 (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook