How Books Designed for Soldiers’ Pockets Changed Publishing Forever

Prior to WWII, Americans didn’t think much of softcover books.

In early June, 1944, tens of thousands of American troops prepared to storm the beaches of Normandy, France. As they lined up to board the invasion barges, each was issued something less practical than a weapon, but equally precious: a slim, postcard-sized, softcover book.

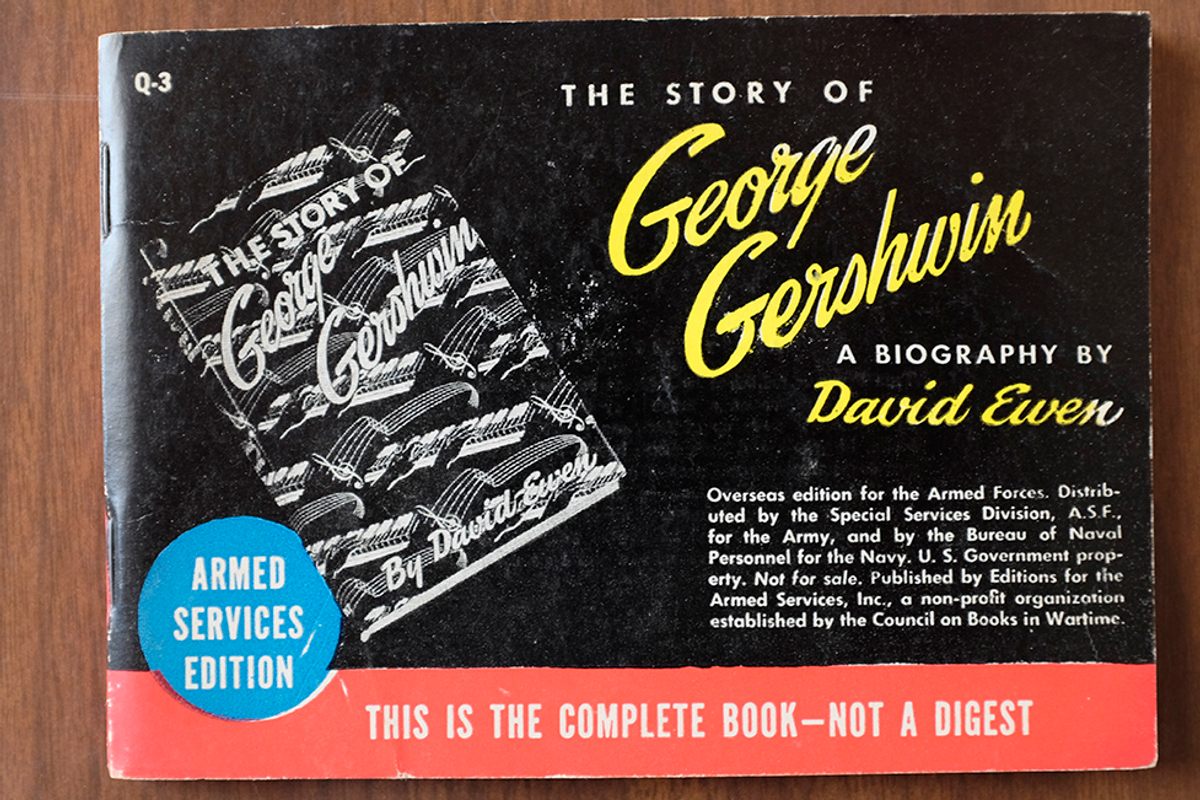

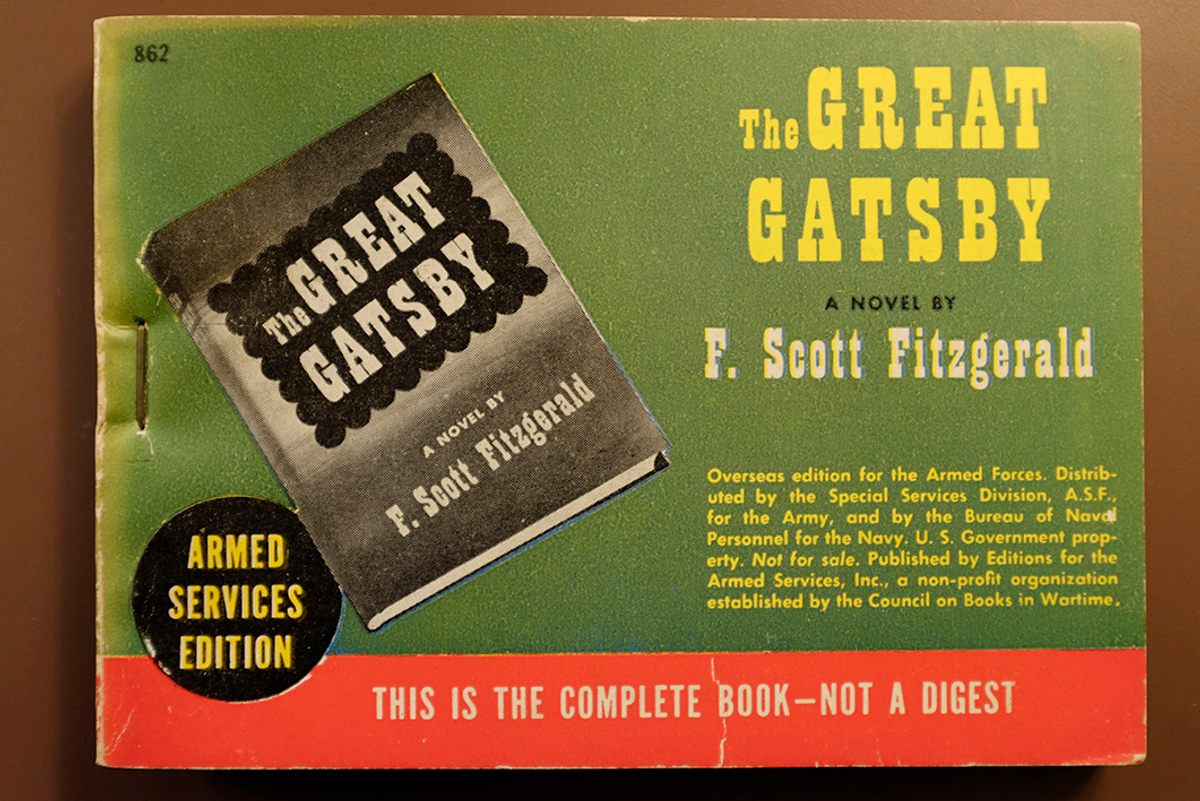

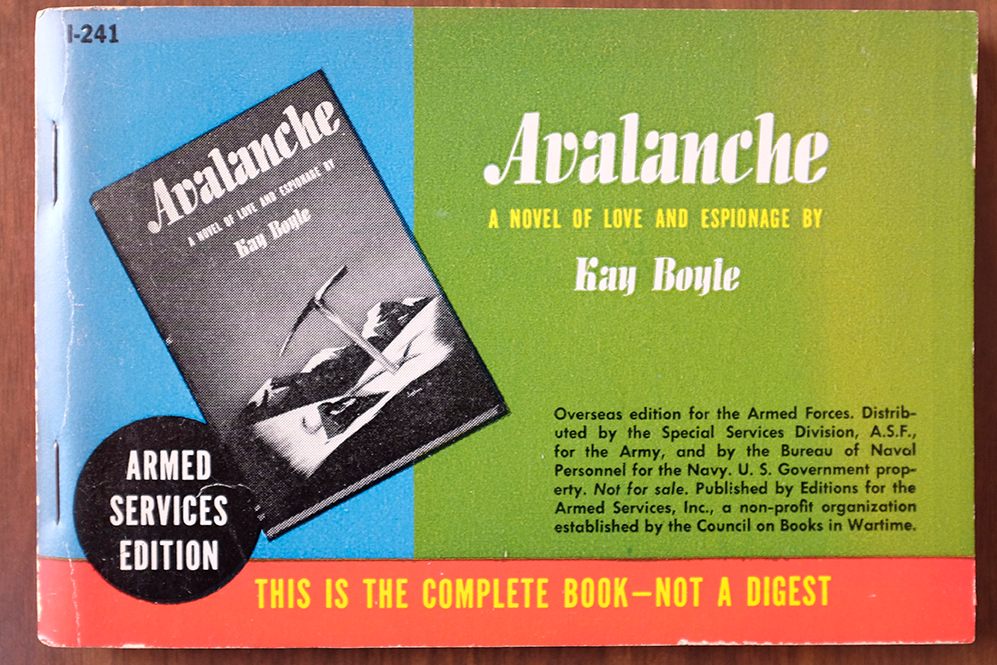

These were Armed Services Editions, or ASEs—paperbacks specifically designed to fit in a soldier’s pockets and travel with them wherever they went. Between 1943 and 1947, the United States military sent 123 million copies of over 1,000 titles to troops serving overseas. These books improved soldiers’ lives, offering them entertainment and comfort during long deployments. By the time the war ended, they’d also transformed the publishing industry, turning the cheap, lowly paperback into an all-American symbol of democracy and practicality.

As the bookseller Michael Hackenberg writes in an essay for the Library of Congress, small books and paperbacks have arisen many times over the course of publishing history, usually in response to some particular need. In 1501, Venice’s Aldine Press began printing octavo-sized editions of Latin and Greek classics for aspiring scholars on the go. (The books were designed to be “held in the hand and learned by heart… by everyone,” their publisher, Aldus Manutius, later wrote.)

The streets of 16th-century Europe were plastered over with paper tracts and pamphlets. In the 1840s, the German publisher Bernhard Tauchnitz began putting out portable editions of popular books, which travelers snapped up to while away the hours during rail journeys, and by the 1930s, Britain was stacked with softcover Penguin Classics, available at every Woolworth’s store.

But in the U.S. in the early 20th century, paperbacks were a bit more of a hard sell. As Hackenberg writes, without a mass-market distribution model in place, it was difficult to make money selling inexpensive books. Although certain brands, including Pocket Books, succeeded by partnering with department stores, individual booksellers preferred to stock their shops with sturdier, better-looking hardbacks, for which they could also charge higher prices.

Even those who were trying to change the public’s mind bought into this prejudice: one paperback series, Modern Age Books, disguised its offerings as hardcovers, adding dust jackets and protective cardboard sleeves. They, too, couldn’t hack it in the market, and the company folded in the 1940s.

At exactly that time, though, another demographic arose that had a particular use for low-cost, portable books: American soldiers. In September of 1940, as the U.S.’s entry into World War II began looking more and more likely, President Roosevelt reinstated the draft. Hundreds of thousands of new recruits soon found themselves in basic training, an experience that, due to a lack of available facilities, often included building their own barracks and training grounds.

Within a couple of years, many of them—along with hundreds of thousands of others—had been deployed. As Hackenberg writes, the U.S. military now consisted of “millions of people far from home, who found themselves in a situation where periods of boredom alternated with periods of intense activity.” In other words, they were the perfect audience for a good paperback.

It didn’t take long for the Army, too, to come to this conclusion. As Molly Guptill Manning writes in When Books Went to War, although books were already considered an important source of troop morale—the Army Library Services had been established during World War I—Nazi Germany’s embrace of book-burning, propaganda and censorship imbued them with new wartime significance. In 1940, after word got out that the newly built camps were starved for books, the Army’s new Library Section chief, Raymond L. Trautman, set out to change that.

As Manning writes, Trautman’s initial plan, which involved using Army funds to buy one book per soldier, fell far short of its goal. In an attempt to pick up the slack, libraries across the country independently organized book drives. This quickly mushroomed into the nationwide Victory Book Campaign, or VBC, a collaboration between the Army and the American Library Association that aimed to be the biggest book drive in the country’s history.

Although the campaign started off strong, collecting one million books in its first month, donations soon slowed—citizens, who were already being asked to sacrifice for the war effort in any number of other ways, couldn’t keep up that initial pace. Many of the books donated—like How to Knit and An Undertaker’s Review—were rejected, as it was assumed, fairly or unfairly, that they’d hold no interest for soldiers. On top of that, the bulky, boxy hardcovers proved bad battlefield companions. In 1943, the VBC was officially ended.

Trautman had to try something different. Over the course of the preceding years, he had consulted with publishers, authors, and designers about how to quickly and efficiently increase the number of books that made it to the troops. In 1943, together with the graphic artist H. Stanley Thompson and publisher Malcolm Johnson, he officially proposed his idea: Armed Services Editions, or ASEs.

These would be mass-produced paperbacks, printed in the U.S. and sent overseas on a regular basis. Rather than depending on the taste and largesse of their overextended fellow citizens, soldiers would receive a mix of desirable titles—from classics and bestsellers to westerns, humor books and poetry—each specially selected by a volunteer panel of literary luminaries.

But choosing the books was only half the battle. As had been proven by previous efforts, in order for this project to be a success, the objects themselves had to be somewhat war-ready: “flat, wide, and very pocketable,” as John Y. Cole, of the Library of Congress’s Center for the Book, put it. Although five different presses quickly volunteered to help make the books, their machines were normally used to print magazines, which, while both flat and wide, were certainly too big for your average soldier’s pocket.

Trautman and Thompson solved this problem by printing two books at a time, laid on top of each other. Workers at the presses printed out the double pages, cut them in half, and sorted them into appropriate piles. The pages were then stapled together—a way of thwarting the world’s many glue-eating insects, and of slowing down the mildew invited by thread.

Because of the varying sizes of the printing presses, two types of ASE resulted: a smaller one, about the size and shape of a postcard, which could fit into a breast pocket, and a larger one, 6 ½ by 4 ½ inches, for the pants pocket. Both kinds were horizontally oriented, almost like a flip book. These design choices weren’t lost on the soldiers: “Whoever made ‘em hip pocket size showed a stroke of genius!” one soldier wrote. “I can’t say it’s next to my heart, but it is treasured.”

The first set of ASEs was released in October of 1943. Each month for the next four years, crate after crate of books made their way to overseas soldiers, pretty much wherever they were. “They have been dropped by parachute to outpost forces on lonely Pacific islands; issued in huge lots to hospitals… and passed out to soldiers as they embarked on transports,” reporter Frank S. Adams wrote in 1944.

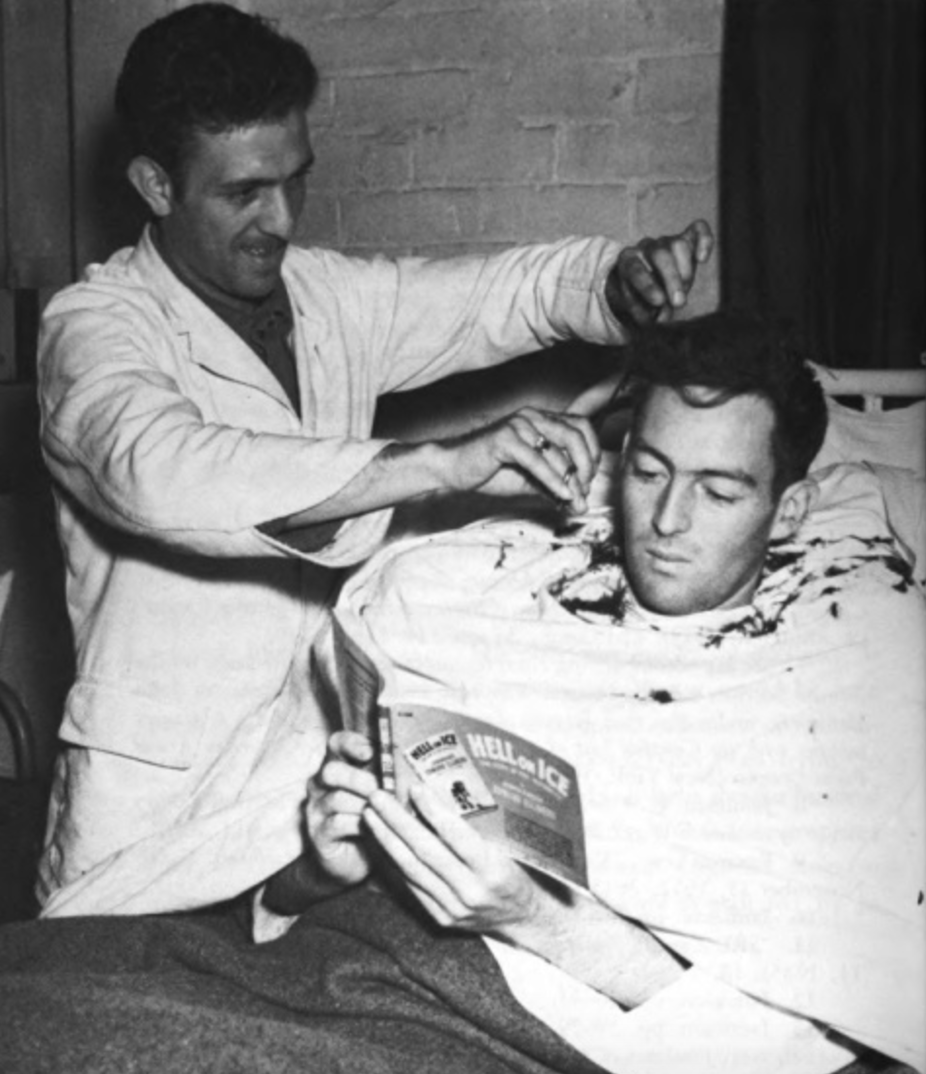

They were a huge and immediate hit. “Never had so many books found so many enthusiastic readers,” Cole later wrote. As Manning tells it, “servicemen read them while waiting in line for chow or a haircut, when pinned down in a foxhole, and when stuck on a plane for a milk run.” Some soldiers reported that ASEs were the first books they had ever read cover to cover. Troops cherished their shipments, passing them around up to and beyond the point of illegibility. “They are as popular as pin-up girls,” one soldier wrote. “To heave one in the garbage can is tantamount to striking your grandmother,” quipped another.

Sometimes, particular titles had lasting effects. Betty Smith, whose A Tree Grows in Brooklyn went out in Shipment D, received ten times more fan mail from soldiers than she did from ordinary civilians. (One, from a 20-year-old soldier who read the book while recovering from malaria, told her that it caused his “dead heart” to “[turn] over and become alive again.”) After Katherine Anne Porter’s Selected Short Stories was chosen, she began hearing from aspiring writers who wanted to discuss technique and craft.

During a Library of Congress event in 1983, veteran Arnold Gates remembered tucking Storm Over the Land, Carl Sandburg’s history of the Civil War, into his helmet before marching to the front lines. “During the lulls in the battle I would read what he wrote about another war and found a great deal of comfort and reassurance,” he said.

This influence went both ways. The soldiers’ enthusiasm brought particular titles—including The Great Gatsby, which wasn’t very popular when first released—a new wave of renown. It also changed the American paperback’s reputation forever. “The ASE series set the final imprimatur on cheap, mass-market reading material,” Hackenberg writes.

From the beginning of the production process, he continues, the publishers involved felt “a sense of pending triumph and of crossing a new threshold.” After the project’s end, in 1947, this instinct was borne out: by 1949, softcovers were outselling hardback books by 10 percent.

So the next time you dog-ear a page of your pocket paperback and slip it into your jacket to accompany you on your commute, think of a soldier. They’re a big part of why it fits.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook