The Real Women Behind Art’s Masterpieces

History’s best-known muses were artists in their own right.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

It was 1991 and Sue Tilley was heading to her second job. When she arrived at the unassuming, brown brick townhouse in London, she said hello to her employer and began to strip. For five years, Tilley posed for British painter Lucian Freud, who completed four canvases featuring her naked, curvy form. In recent years, those paintings have become some of Freud’s most expensive, garnering tens of millions of dollars at auction.

But Tilley was far more than just a model, says art historian and author Ruth Millington. She was a muse, an active participant in artmaking, bringing her presence and creativity to each painting. “I made Freud appreciate the fuller-figured woman,” Tilley told Millington. Millington’s new book, Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces, explores the lives of 30 of art history’s greatest muses, demonstrating how they, like Tilley, inspired the artists they worked with. Atlas Obscura talked to Millington about the history of art’s muse, the woman who dressed Gustav Klimt’s models, and why the contributions of female muses are so often overlooked.

How do you define the role of the muse?

The muse’s role is to inspire an artist in some way beyond a model who is simply paid to pose or someone who might commission a portrait. There has to be a human connection between these two people, something deeper than just an artist painting a life model.

What’s the difference between a muse and a model?

[British fashion photographer] Tim Walker told me he can easily differentiate between model and muse. A muse always meets him halfway. With a model, he has to tell them what to do and direct them completely—anybody can do that. But with the muse, they’re influencing the picture in some way. He calls, “a true portrait a handshake between two people.”

How does the idea of the artist’s muse shift through history?

In the Renaissance, muses are allegorical figures. They are classical, divine goddesses. In the 19th century with the Pre-Raphaelites, there was this shift to muses being real-life people, particularly women. A lot of women were cut out from actually being artists. They weren’t able to go to figure-drawing classes or exhibit publicly. So that’s when these male artists, particularly the Pre-Raphaelites, began to take wives, sisters, and cousins as their muses.

At the same time, a lot of women used the position of muse quite cleverly. Elizabeth Siddal is a good example of this. She wanted to be an artist and she actually approached the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood wanting to exhibit with them. But she was also happy to model for them as a way of breaking into their ranks. It worked well for her because she went on to exhibit with them both in the UK and America.

Can you describe a muse/artist relationship where a muse doesn’t necessarily model for the artist?

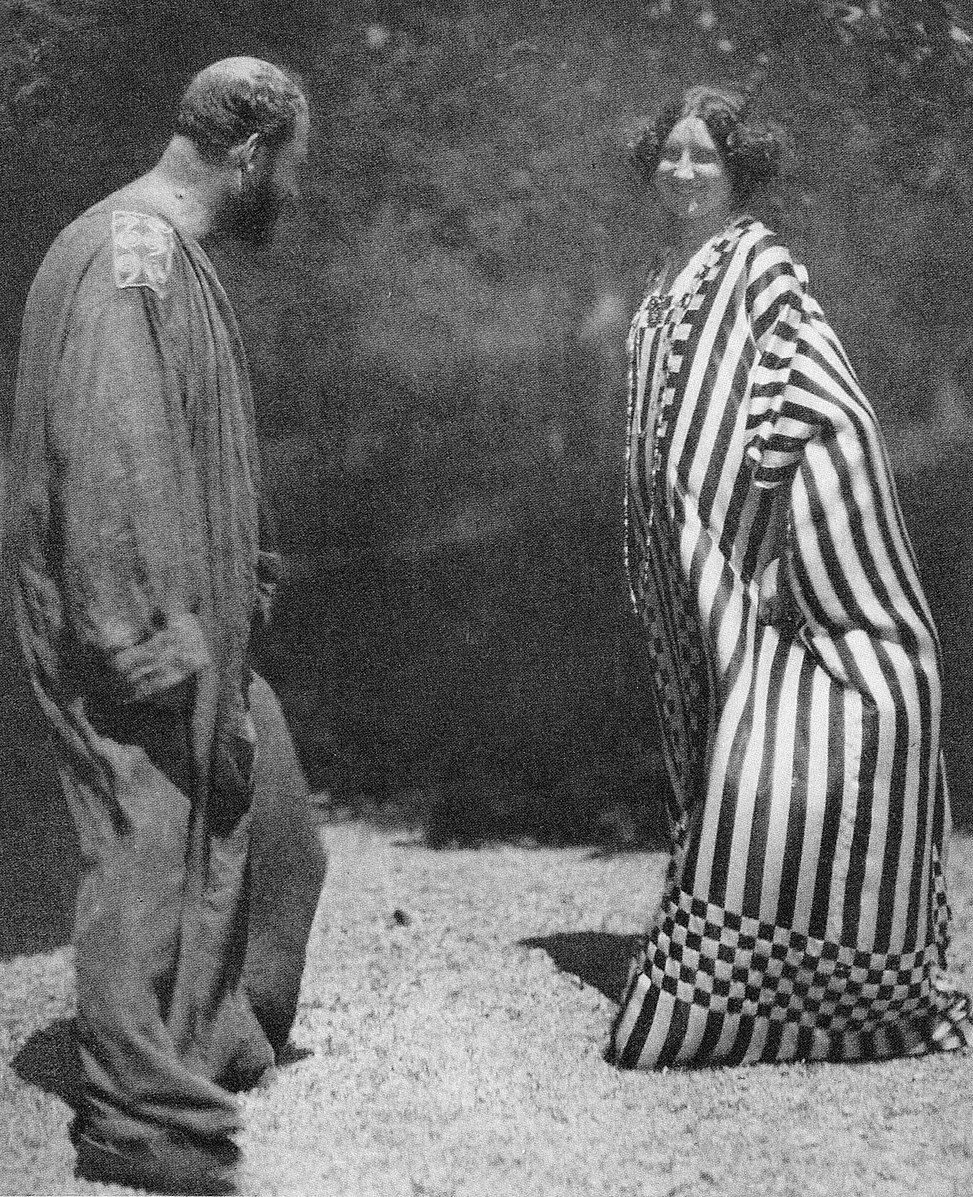

I think a really good example of this is Gustav Klimt. Everybody knows Klimt’s style. It’s super decorative. All the women in his paintings are wearing really loose robes, beautifully decorated. And his muse, Emilie Flöge, was a fashion designer in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. They were both interested in moving art away from this idea of traditional fine art and into art moving across all aspects of life.

Flöge is really revolutionary. She has her own fashion store in Vienna. She managed the business. She designed the dresses. She sold the dresses. She also exhibited all this folk art in her store. And all these designs of hers can be seen reflected in Klimt’s paintings. She does appear occasionally as a model, but more often than not, it’s the women she dressed who appear in Klimt’s paintings. All of Klimt’s male contemporaries were painting nudes, and he was dressing his women up in these designs. Klimt and Flöge actually ended up working on dress designs together. And he even modeled some of her clothes. There are all these photographs of them on a lake wearing these long dresses. You can see they are collaborative partners, kind of mutual muses.

What role does gender play in the fact that female muses have often been overlooked?

I think men have used the term muse to keep women in their place. I feel like Picasso and other 20th-century artists played into these myths of the muse. That’s when you see them using the word “muse” in titles of artworks to elevate themselves. They were presenting this idea that to be a great artist, you could and maybe even had to be in possession of a muse. They also frame the muse in this power imbalance. “Artist” is active. “Muse” is passive. You see this shift to presenting the muse as a female romantic partner who is submissive to the male artist.

These artists were also using the term “muse” to hide the contributions of these women, like Dora Maar influencing Picasso’s style and his subject matter. Maar introduced Picasso to her ultra-left-wing politics at a time when it was really rare for women to be a member of such parties. And she also introduced Picasso to photography. She led Picasso into thinking more about politics and influencing his subject matter as his style moved into black and white paintings. If you look at “Guernica,” he hadn’t painted like that before Maar. But he doesn’t want to acknowledge that.

How do you wish people would think and interact with art?

I hope when people go to a museum or a gallery or even see an artwork online, they might ask the question: “who made this work?” There’s always one name attributed to a masterpiece, but they might think who else was involved in the construction of this artwork, either physically or emotionally?

I’d also like people to separate the ways people are depicted from the real women behind the work. Particularly with the Pre-Raphaelite paintings, we think of the muses as how they are shown in the paintings when actually they were playing characters. Elizabeth Siddall dressed up as Ophelia, and she’s now associated forevermore as a tragic doomed heroine. But she was just playing a role. People have just gone along with these myths of the romantic muse at the mercy of this older male artist when actually the stories are way more complex than that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook