How to See the Poetry in Plants

A botanist made fantastical sketches of the rain forests’ natural wonders.

Researchers who work in tropical rain forests often speak of the hassles of it all: Whacking through dense vegetation is tricky, especially when you’re lugging gear and need a free hand to swat, with utmost futility, at the swarm of insects buzzing around your head. And then there’s the rain, which soaks through clothes and patience alike.

But they also talk about how it’s all worth it. These places are precious and shrinking and so little understood. Even researchers who regularly embark on collecting trips to rain forests find, time and again, species that are new to science, from plants to carnivorous insects and more.

Scientific discovery is important, but wonder fuels these adventures, too. At least, that’s the case for Francis Hallé, a French botanist who has spent decades exploring the world’s rain forests. A professor emeritus from the University of Montpellier, Hallé knows that a forest is not just data. He reflects on his time below the branches with great affection, even awe. In a short film from the “Worlds in Transformation” series by the storytelling collective La Foresta, he grows wistful when he recalls drifting off to sleep in the forest, to the symphony of insects and birds around him. He likens the canopy, one of his areas of professional interest, to a sea—only green, and airborne.

Much like the sea, rain forests hold natural wonders that aren’t visible until you’re right up close. Equatorial forests are “a universe of magical allure,” full of “little marvels,” Hallé writes in The Atlas of Poetic Botany, a volume of his Seussian botanical sketches and informed musings, produced in collaboration with Éliane Patriarca and newly translated into English by Erik Butler. In damp, sticky forests from Sumatra to Robinson Crusoe Island, he writes, “there is an abundance of aesthetic satisfaction, wonder, and poetry to be found.”

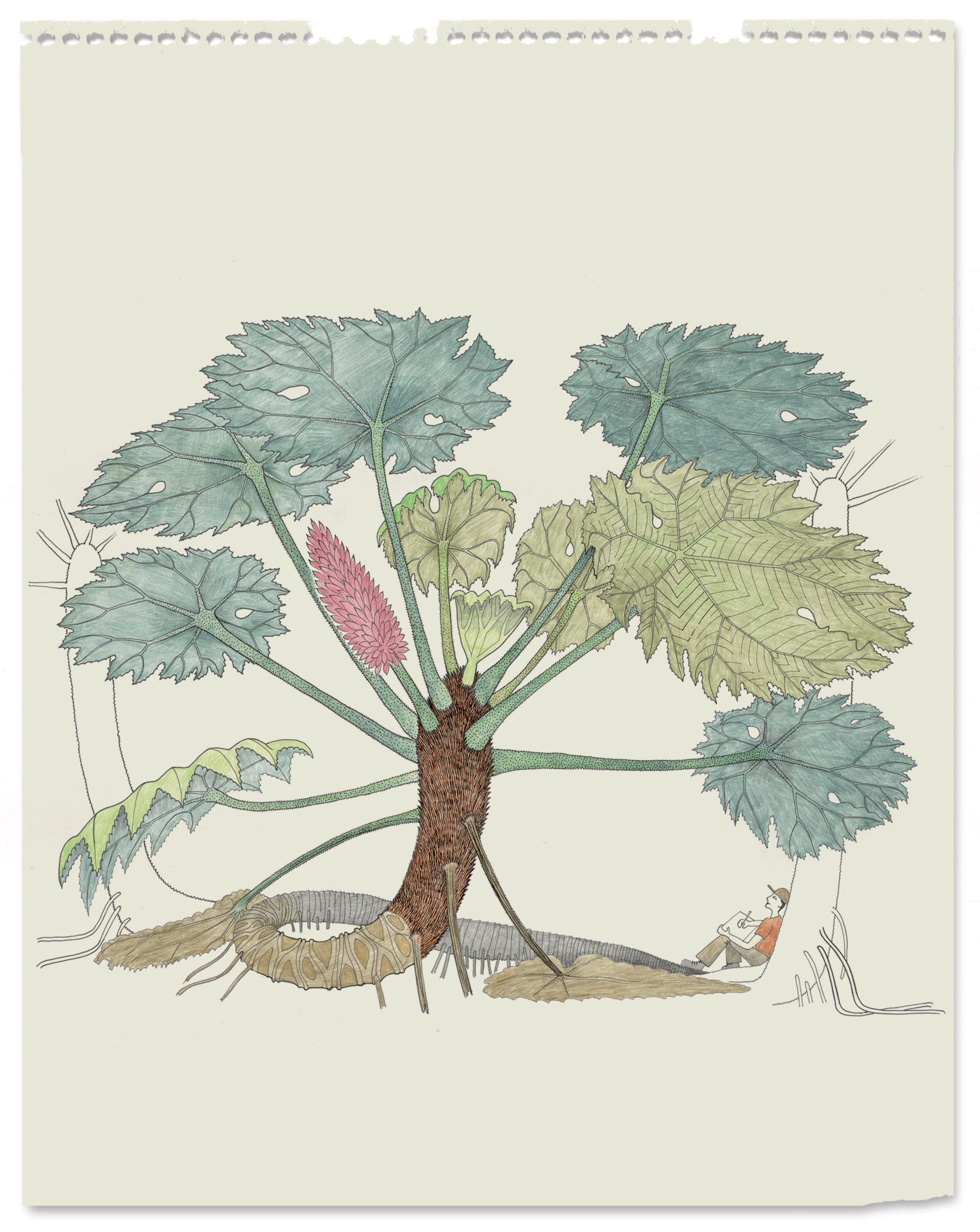

Each entry in the Atlas drops readers into a scene of Hallé’s fieldwork. On Robinson Crusoe Island, part of an archipelago off the coast of Chile, he found Gunnera peltata, which looks like a rhubarb plant so enormous that it dwarfs whoever stands below its wide, veined leaves. Analyzing it was a thrilling challenge. “Normally, a scalpel is used for dissecting plants,” Hallé writes. “This time, I had to wield a meat cleaver!” A photo would convey the size and the “nest of ruby-red fibers,” but the author eschews snapshots. “I cannot think of a better way to present it than with a drawing,” he says.

There’s a long history of sensitive, precise, and scientific botanical illustration, and more recently scientists turned to stunningly detailed photographs of their subjects, in which, say, an insect’s bristles or compound eyes are presented for close-up study. Hallé prefers to take it slower and simpler. Drawing invites lingering, he writes, which in turn invites people to look closely, carefully, hungrily. To understand a plant, “it is best not to rush.” The time it takes to complete a sketch “amounts to a dialogue with the plant,” and each pencil stroke helps imprint the scene in your mind.

In the sketch accompanying the G. peltata, green and blue-gray stalks stretch above a dusty-rose flower. The coiled trunk is surrounded by others, whose canopies vanish into the margins. In the corner, someone reclines against a trunk that seems to follow the curve of his spine. He’s looking at the plant, admiring it, maybe drawing it, a grin sweeping across his face. The image seems to freeze a moment—perhaps Hallé’s own encounter with the plant, which his drawing helped sear into his memory. “I will never forget my strolls through the Gunnera forest,” he writes, “beneath a roof of gigantic leaves.”

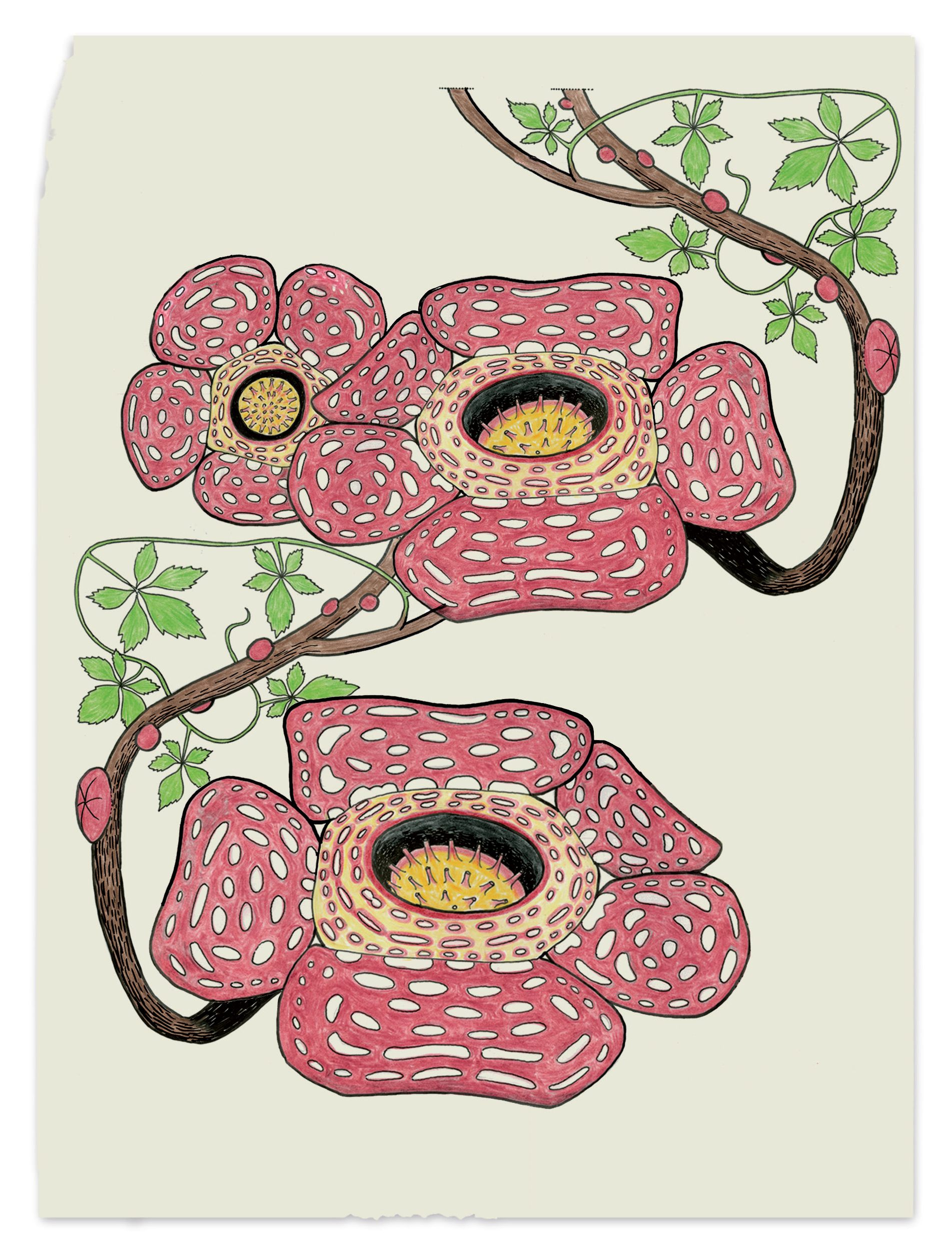

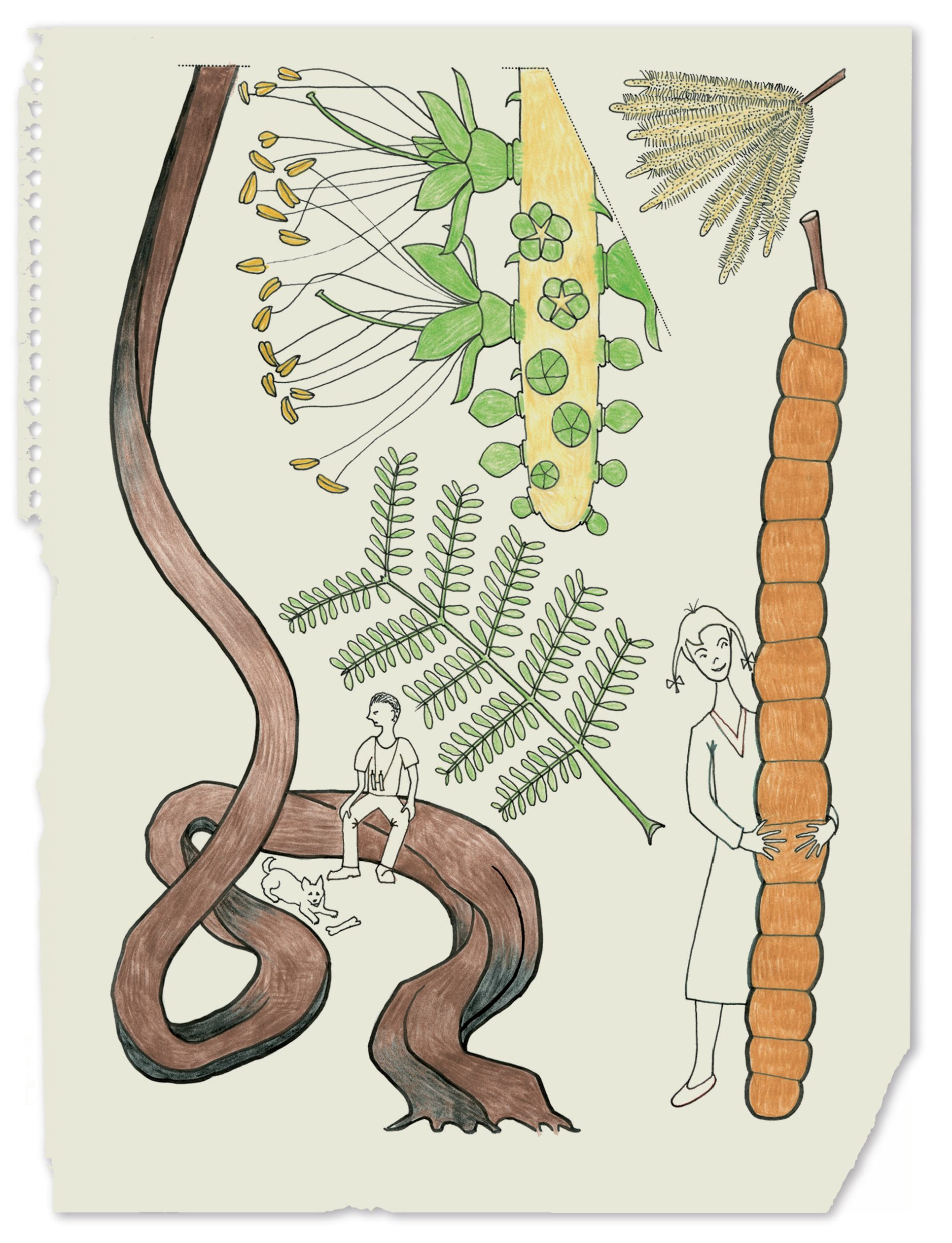

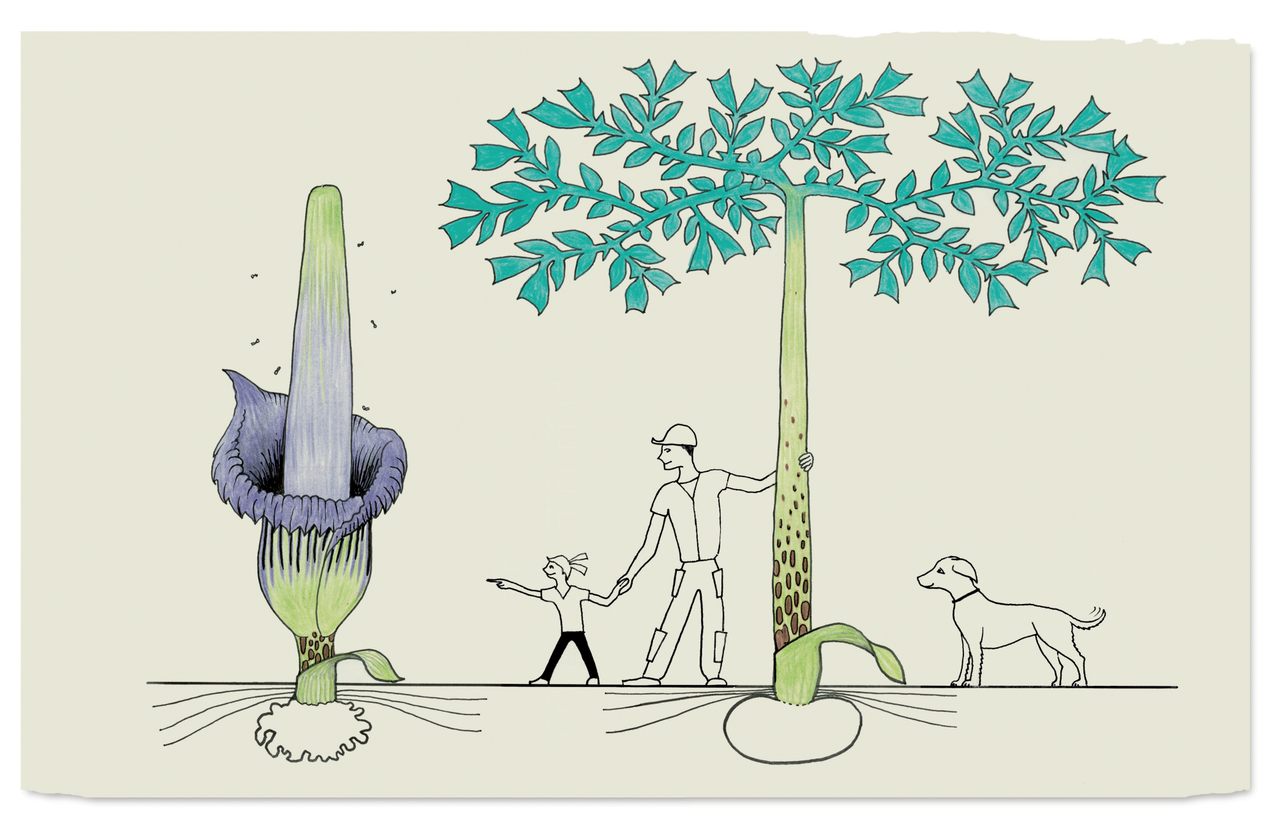

Almost every illustration in the book is infused with this sense of delight in the pleasant strangeness of the natural world. Yes, that includes the sketch of Rafflesia arnoldii, the corpse lily, the largest and possibly foulest-smelling flower on the planet. Its petals are pink (“the color of rotten meat,” Hallé writes), and its scent is rank—a “pestilential odor” that evokes “clogged toilets, or a garbage collector strike in the middle of August.” The two kids in the drawing don’t seem fazed. They’re grinning. One even wraps his hand around the branch, like he’s patting a buddy on the shoulder. In another image, a woman cuddles the gargantuan seed pod of Entada gigas, a Central African vine that might be the world’s longest plant. The pods grow to about 6.5 feet, but no one has been able to measure the vines, Hallé writes, because they’re hard to reach. Nature is stinky, mysterious, and elusive, and the figures in his drawings are totally into it.

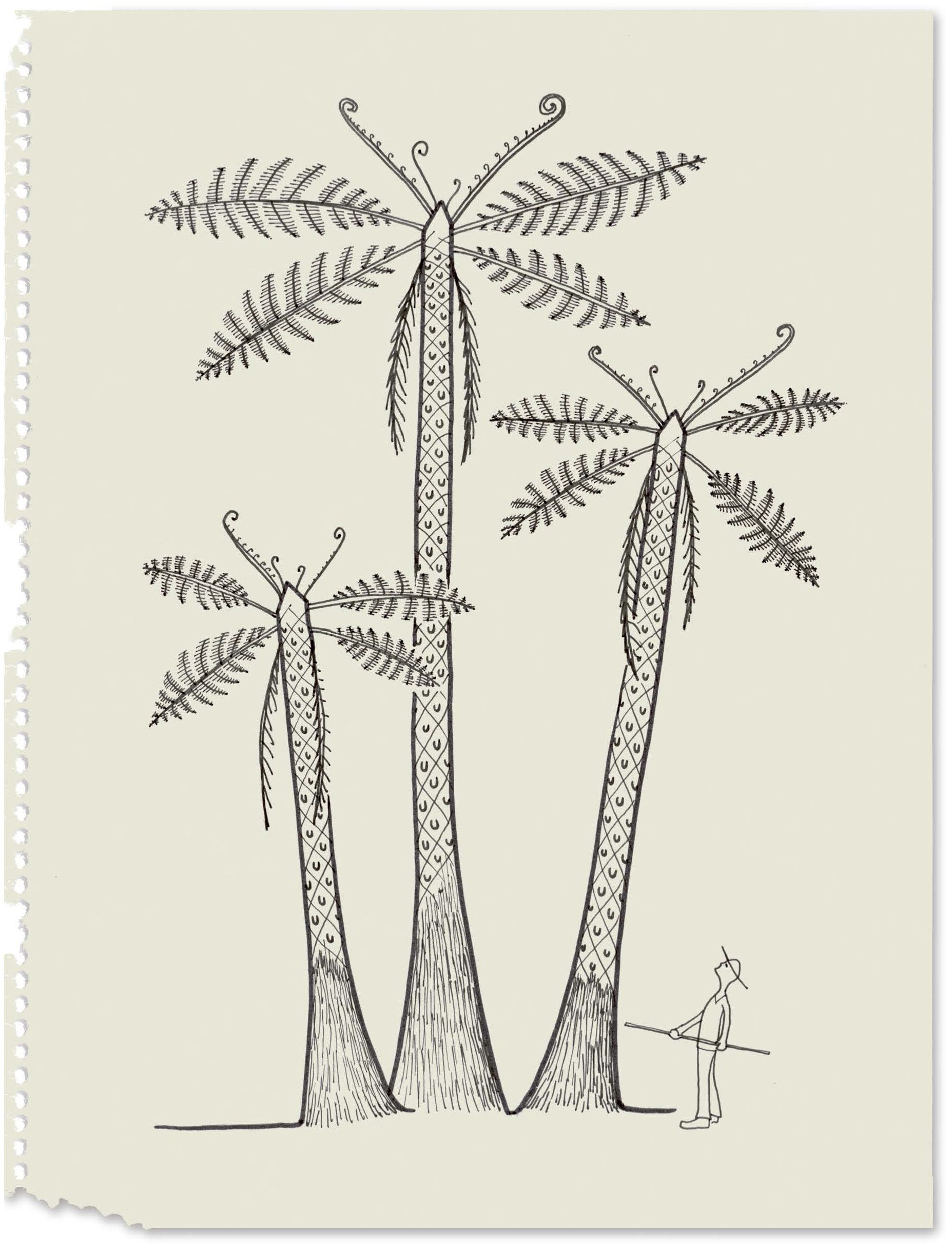

These figures do offer a sense of scale, probably, but also seem to remind readers that sights such as the great African tree fern (Cyathea manniana) are worth reveling in. Anyone who encounters one would be well-served to do as Hallé’s little character does: Stare up, up, up at the palm-like plants that have sprouted in thick clusters for hundreds of millions of years, and saw the dinosaurs come and go.

The book is not an exhaustive checklist of any region’s flora or fauna, nor does it gather everything scientists know about a particular plant. Instead, it’s a tenderly illustrated love letter to specimens that most people will never see outside a conservatory’s glass walls—and to the sights, smells, and sounds that flank the trunks, stems, and petals. If there’s a thesis, it’s that nature is wondrous and bizarre, and we’re extremely lucky to live alongside it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook