Archaeologists Are Seeing Cave Art in a New Light

Prehistoric people may have created ‘proto-cinema,’ with galloping bison and tail-swishing horses.

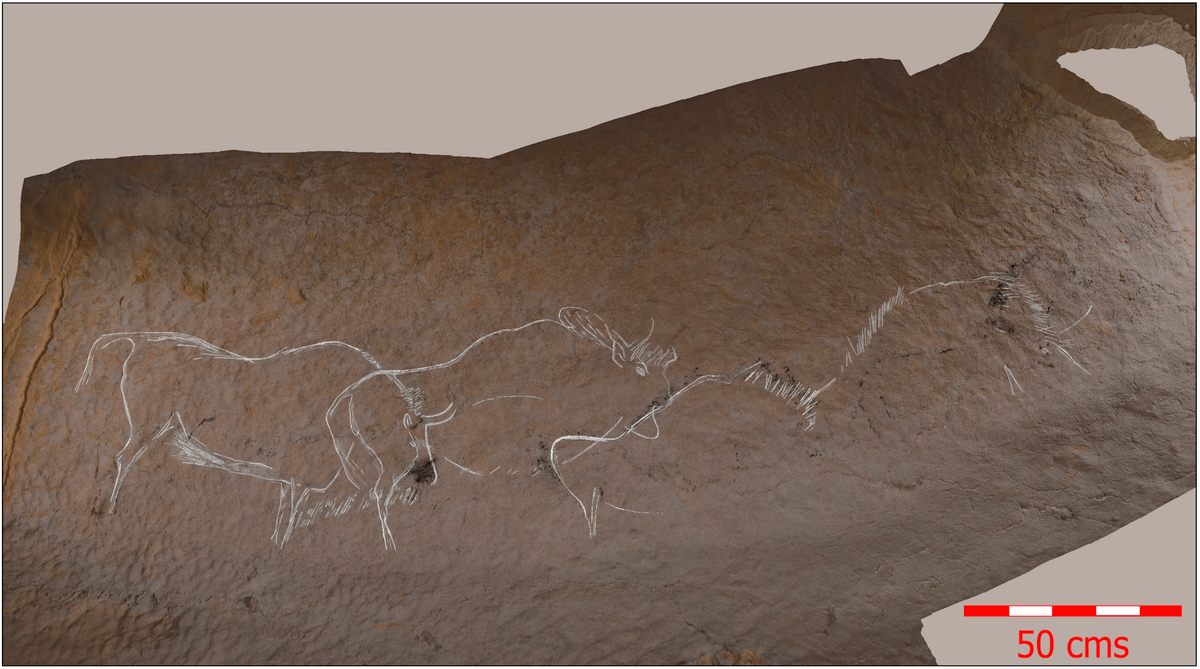

A small group of artists, carrying engraving tools, torches, and other supplies, assembled at the base of the towering limestone outcrop, near the mouth of a dark cave. Together, they entered the lightless space. For 40 minutes they wormed through passages and scrambled over speleothems. Their juniper-branch torches cast a warm, flickering light and shed bits of charcoal like bread crumbs along the trail. Nearly a quarter-mile from the cave entrance, they reached their canvas: a rugged limestone wall, 40 feet long and eight feet above the cave floor. They set the torches aside, lit stone lamps greased with marrow, and climbed onto a ledge that ran along the wall’s base. There, they began their work. At this spot in what’s now northern Spain’s Atxurra Cave, some 12,500 years ago, the artists carved scores of horses, bison, deer, and mountain goats. The animals’ outlines fluttered and winked in the light thrown by the lamps.

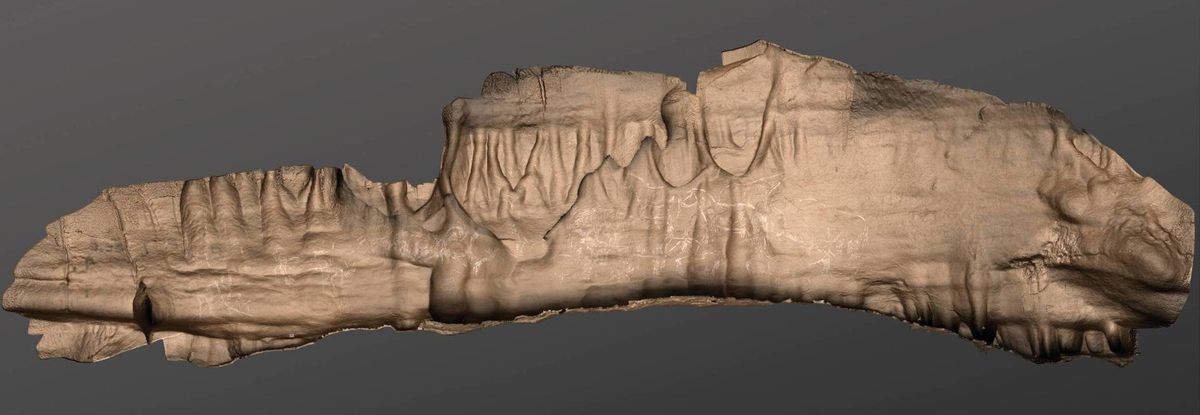

In 2015, two scientists rediscovered this masterpiece, now known as the Ledge of Horses, along with dozens of other carvings and paintings in other hard-to-reach corners of Atxurra Cave. Faded by time, some figures had nearly vanished. Researchers flooded the chambers with LED lights and took photographs, which they ran through software to detect elements not visible to human eyes. They recreated the art in digital form, allowing the modern word to behold it.

A technical achievement, yes, but the ancient artists never saw their works in the static, white light of electric bulbs, or via computer screens. As researchers continue to discover engravings and paintings deep underground, they also want to understand how—and why—past people made and viewed the images. Now, new experiments are providing important insights on the logistics of creating ancient cave art, and perhaps a glimmer of the intent behind it.

Roughly 38,000 years ago, Paleolithic people in Western Europe began braving dark caves to create some of humanity’s earliest art. Famous sites in present-day France and Spain, including Lascaux and Altamira, feature stunning geometric designs, handprints, and paintings of Ice Age beasts up to 17 feet in length. In a 36,000-year-old scene in Chauvet cave, lions grimace and pant as they chase a herd of bison.

Such cave art has long puzzled researchers: These works were concealed in darkness, and probably viewed by an occult few, yet the figures took considerable time and technical mastery to render. Why would Paleolithic people, already occupied with finding food and other necessities, devote precious time and energy to creating art hidden hundreds of feet from daylight?

“The debates are huge. And everybody has these great arguments and all sorts of interesting things to say about it,” says archaeologist Holley Moyes, an expert on subterranean rituals and professor at the University of California, Merced.

Over the years, archaeologists have proposed that Paleolithic societies created the art as part of hunting rituals or psychedelic drug trips, or as historical records, teaching devices, or graphic novels, where a series of panels conveyed a continuous narrative. In some caves, animals or parts of their bodies are rendered several times, juxtaposed or superimposed in different positions. The light and shadows thrown by flames may have created the illusion that these figures were moving, according to some researchers, who call this art form “proto-cinema.” At Chauvet for example, the painting of an eight-legged bison might have appeared, by torchlight, to be a four-legged animal striding across the wall.

Marc Azéma, an archaeologist and filmmaker, made this case in his book La préhistoire du cinema [The Prehistory of the Cinema]. In 12 French caves, Azéma identified more than 50 animal figures that might have been drawn to look as if they were galloping, tossing their heads, or swishing their tails.

“The flickering light, the dancing shadows, the warm glow from the fire, many people have argued that this creates a sense of theater, that you’re looking at an ancient version of cinema,” says University of Victoria archaeologist April Nowell.

Nowell and colleagues have designed electric lamps to emit light with the same color, intensity, and flicker as Paleolithic flame lamps. The research is ongoing, but Nowell was awestruck when they tested the devices in Koonalda Cave, Australia. There, after a “terrifying” climb up a 260-foot slope, they gazed upon a wall as long as a football field that was covered with streaks and swirls made at least 20,000 years ago.

Then they shut off their conventional lights and switched on the flame mimicking lamps. Nowell still marvels at the effect: “I don’t even know how to put it into words.” The lamps “gave this feeling of intimacy and warmth in the cave that is just missing with our modern technology.”

Scientists don’t use actual flaming torches in archaeological sites because soot could damage artifacts and other material. So, while some researchers develop devices that mimic ancient torches and lamps, others test their hypotheses in caves that don’t have archaeological remains. For example, Iñaki Intxaurbe, a doctoral student in geology at the University of the Basque Country, recently analyzed how much effort the Atxurra artists expended just to access spots where they left their mark—the ancient art is found only in the cave’s deeper passages, 600 feet or more from the entrance. The most elaborate scenes were also along ledges up to 16 feet above the cave floor. To reach them, “you need to climb,” says Intxaurbe, who has a special interest in Atxurra: He and University of Cantabria archaeologist Diego Garate were the duo who discovered the Ledge of Horses there in 2015.

For his recent paper, published in January in the Journal of Archaeological Science, Intxaurbe tracked the pace of more than 20 cavers and scientists as they moved through a cave similar to Atxurra but without archaeological remains. Based on that data, he was able to estimate how long it would have taken to reach the Ledge of Horses and other Atxurra artwork. His results confirmed that the artists chose areas that were particularly difficult to access. The art was meant to be hidden.

Artists and any audience for their work would have needed light to reach the sites, and to view the art. As part of her doctoral research at the University of the Basque Country, archaeologist M. Ángeles Medina-Alcaide and colleagues built torches, stone lamps, and a bonfire, modeled after artifacts recovered from rock art sites. They tested the replicas in another art-free cave near Atxurra, measuring light properties and monitoring air quality.

The experiments, published last month in PLOS ONE, revealed that torches worked best for traveling through the cave, but lasted an hour, tops. The grease lamps, which burned longer with less smoke, were ideal for extended stays in small corridors. A bonfire built on the cave floor cast the most light, but filled the chamber with smoke (and ended the experiment) within half an hour.

“This is fabulous data,” says Moyes, who was not involved in the research. “They’ve done such a good job of quantifying the different types of light and the different light sources, and no one else has really done that.”

Medina-Alcaide’s team then applied the findings to Atxurra. For the 40-minute trek to the Ledge of Horses, and the return trip to daylight, the Paleolithic people would have needed at least two torches. While engraving and painting, they probably used lamps. Using a virtual model of Atxurra, the researchers found that the Ledge of Horses art would have been barely visible to people standing on the cave floor. However, fires built directly on the ledge, eight feet above the cave floor, would have illuminated the entire scene, with smoke collecting above, rather than around, people standing below.

The paper’s conclusions fit with archaeological evidence at Atxurra. Ashes, charcoal, and other signs of a hearth were found on the ledge, indicating multiple fires had been built there. More charcoal fragments and smudges suggested torch use in the passages leading to the decorated chambers.

Azéma welcomes the research and considers it to be a step that’s “essential to understand this art… the placement, the composition, the movement.”

During the experiments with flames, Intxaurbe says he and colleagues also experienced the movement of images that Azéma wrote about in French caves. Perhaps that was the artists’ intent, to transform the cave into a cinema where the bison wink and the horses trot.

“We don’t know why [Paleolithic people] put these paintings in the backs of caves,” says Moyes. “We may never know.” But, she adds, these kinds of experiments provide critical insights, as do archaeological remains, including pigments, fire traces, and the art itself. While the reason Stone Age artists rendered exquisite figures in these dark spaces continues to elude us, we can at least experience this art as our ancestors did—in warm light and dancing shadows.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook