Remembering the London Refuge for South Asian Nannies Far From Home

Abandoned by their employers after a months-long sea voyage, countless women found shelter here.

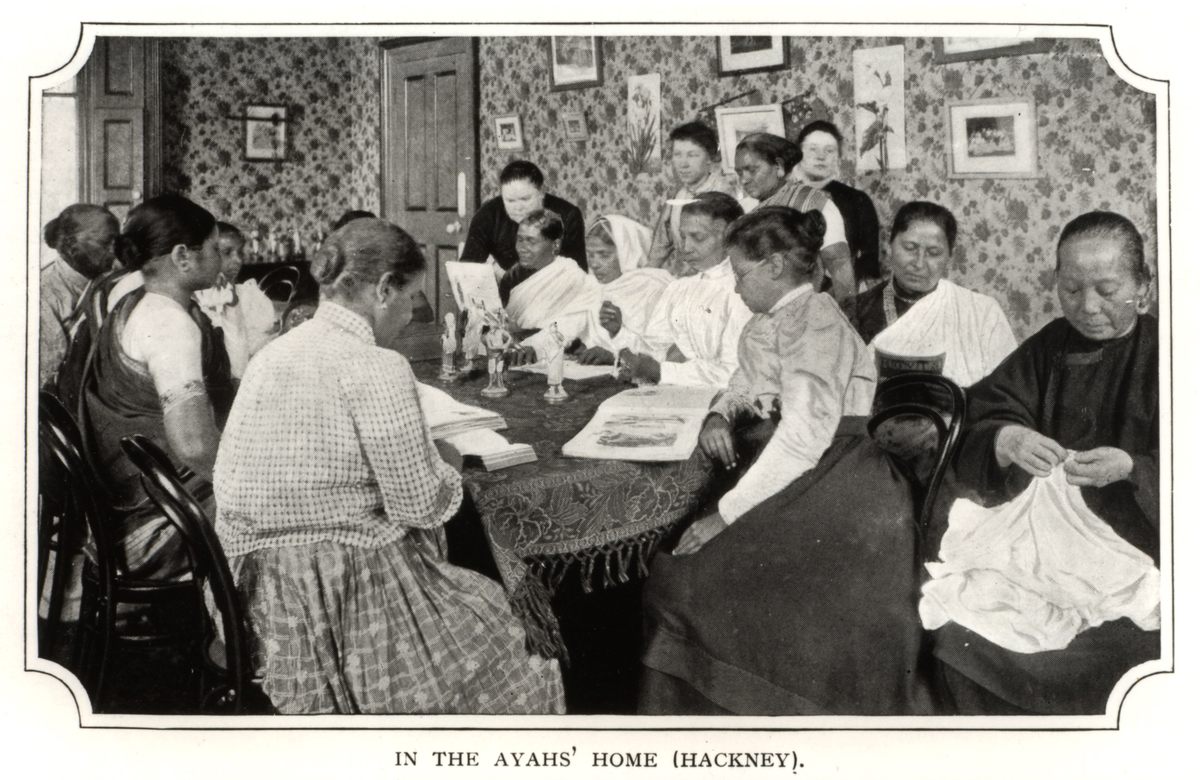

Sunlight pours into a room with floral-patterned wallpaper, where a coterie of women sit around a large table. Dressed in collared blouses and plain skirts or saris, the women sew and read with immense focus, aware of the watchful presence of other women standing behind them. This moment, possibly staged, was captured in a photograph in 1904, in the borough of Hackney. It is one of the rare records of the Ayahs’ Home, a refuge in East London for colonial South Asian ayahs who had crossed oceans caring for British children, only to be abandoned in a foreign country far from home.

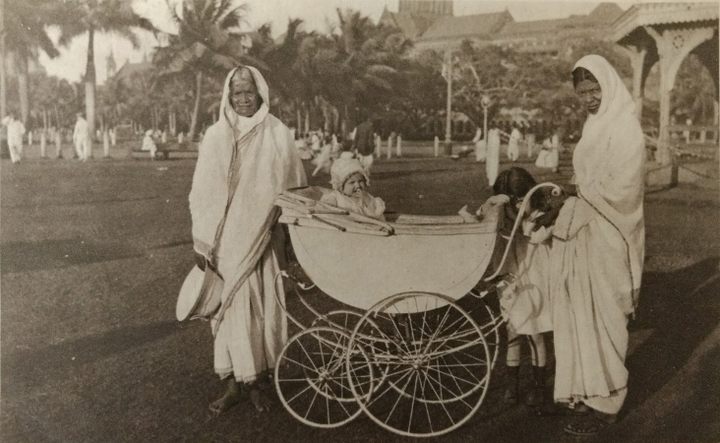

Ayahs were once the backbone of British households in India. Colonial families hired the women as nannies and expected them to be quintessential caregivers: soft-spoken, maternal, faithful, capable, and attentive. Draped in plain white saris, their heads often covered, the women sang lullabies to their charges, rocked them to sleep, and narrated enchanting fairy tales. In return, the ayahs were cherished by their little masters, and were indispensable for British mothers, particularly at sea.

Between the late 1700s and mid-1900s, countless ayahs traveled under the employment of British families. Maritime voyages were long and arduous, marked by bouts of seasickness and dangerous storms. The ayahs relieved memsahibs of their childcare duties by tending to their young and often anxious charges, and keeping them entertained for hours, day after day. Upon disembarking in London or other port cities, however, their services no longer required, a number of the ayahs were unceremoniously discharged. There are no records documenting how many ayahs found themselves in this position, or how most of them fared.

Some of the women found their way to the Ayahs’ Home. Established in 1825 in Aldgate, near the Tower of London, the Ayahs’ Home eventually relocated to a building on King Edward’s Road around 1900 before moving again, a few doors down the street. Run by Christian missionaries from the London City Mission, the home’s name was painted in bold white letters on the arch over its front door. Here, Asian governesses and nannies, steamer trunks in tow, trickled in from all parts of the sprawling Empire, including Hong Kong, British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Burma (Myanmar), Malaysia, and Java.

“The home had very high ceilings,” says historian Rozina Visram, author of Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History. “It was bright and colorful.” Visram began researching the ayahs more than three decades ago. Within the home, there were 30 rooms, she adds, noting that the sleeping quarters were divided by ethnicity and nationality.

Little is known about the ayahs who stayed there; their personal stories were rarely recorded. The London City Mission, however, routinely published articles about the Ayahs’ Home in its magazine. “In fact, the materials which have survived about the ayahs are mostly from these magazines,” says Satyasikha Chakraborty, a historian at The College of New Jersey. “So, you have to be cognizant of the fact that the magazine was a kind of propaganda tool, where the London City Mission would normally write good things about the institution.”

Other publications noted the home. Chakraborty shared a September 1923 article from the Yorkshire Post that described how the ayahs spent their days at the establishment, engrossed in intricate embroidery work, playing cards, or trading stories. Chewing betel leaves was one of their “simple pleasures,” according to the article, as the women sat cross-legged on the ground, indulging in a game of pachisi and tossing cowrie shells in the air as dice.

The ayahs belonged to different cultures and backgrounds, yet a common thread that bound their experiences was the lengthy sea voyage. “While the idea of going to the motherland of the Empire may have been exciting for some, for others it would have been traumatic, because some were leaving their own children behind,” says Jo Stanley, an independent historian who has written extensively about gender and maritime history. “Moreover, some ayahs would have felt very uncomfortable crossing the dark waters, especially since the sea was still a mysterious element back then. In the early 19th century, some believed they would lose their caste by sailing. Not many women, of any color, traveled much in that period.”

Over time, some ayahs appeared to have mastered ocean crossings. British mistresses sought out these “good sailors” by placing advertisements in the newspapers. An ayah whose name was recorded as “Mrs. Antony Pareira” reportedly made 54 voyages. Silver-haired with round, dark eyes, Pareira is described in the London City Mission magazine in 1922 as a “plainly self-reliant” woman with a calm disposition and maternal aura.

“What’s interesting about Pareira’s voyages is that she, like about half of the traveling ayahs, travelled deck class, which meant sleeping out on deck on a little mat, while her British family travelled first class,” says Stanley. “In fact, this was one of the ways families saved money, by transporting the ayahs on cheap tickets.” The duration of a sea voyage from India to England took up to six months, depending on the route.

“I managed to track down two voyages that somebody named Pareira had done around that period,” Stanley adds. “But I don’t think she could have done 54 trips—there’s no evidence of that. I think maybe the reporter misunderstood her. Perhaps, she might have said, ‘five, four trips,’ or maybe she was exaggerating.” The trips she did take may have been set up through the Ayahs’ Home, which also served as an employment agency, connecting the women with British families who were traveling to India or other colonies. The establishment’s priority, however, was something else.

“The home’s main concern was to Christianize the ayahs,” says Visram. “The attitude towards them was very colonial.” The women were taught hymns and escorted to church, and encouraged to talk about Christianity in their quarters. While there is no record of how many ayahs were baptized, Chakraborty speculates that some women may have agreed to convert for certain benefits. “My sense is that conversion probably meant warmer blankets or better treatment,” she says. “If a British family was sailing to India and wanted to recruit an ayah, maybe a Christian ayah would get a preference.”

Hackney resident Farhanah Mamoojee has been single-mindedly working towards raising global awareness about colonial ayahs, and bristles at what the women may have experienced at the home. “We don’t know if they were allowed to practice their own religion or if they were demonized in any way,” she says.

With the collapse of the British Empire in the mid-20th century, the need for ayahs dwindled, and so did their numbers. The building at 4 King Edward’s Road is now home to private residences. Mamoojee first heard about Ayahs’ Home while watching a documentary that briefly mentioned it. In September 2018, she visited the site and discovered there was no sign indicating its historical and cultural importance. “That just really touched a nerve,” she says. As a South Asian woman living in East London, Mamoojee felt connected to the ayahs’ untold stories. The home symbolized their collective struggles and shared but nearly forgotten histories. “I thought the Home was something which was deeply significant and would really mean something to the local community here, because it meant something to me.”

Mamoojee applied for a blue plaque—a sign placed at historically significant sites in the United Kingdom—to recognize, celebrate, and honor the Ayahs’ Home. In February, she received approval for it. She also started an Instagram page to collect what little information exists about the women. However, she says it’s been next to impossible to learn the ayahs’ fates or trace their descendants, “especially since the ayahs were not recorded in ship ledgers under their own names, but (those of) their employers, like, Ayah Smith or Ayah Jones,” says Mamoojee. “So, we actually don’t know who they really were, where they settled, or what happened to them. They really got lost in history.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook