In England, Bar Hill’s ‘Skull Comb’ Is an Iron Age Mystery

The unusual artifact hints at how ancient communities may have treated their dead.

Fens and farmland dominate England’s Cambridgeshire. The A14 runs the length of the entire county and, just a few miles northwest of the ancient university town of Cambridge, it passes by the small village of Bar Hill. There, during excavations a few years ago, archaeologist Michael Marshall and his team found something extraordinary: a piece of ancient human skull, carved to resemble—almost, but not quite—a comb.

It’s not unusual to find artifacts in this corner of England, which has been inhabited for millennia. In particular, Cambridgeshire was home to several Iron Age settlements, dating from around 350 BC to the arrival of the Romans about 400 years later. Marshall and his colleagues knew they would turn up some interesting things when they began digging in 2016 ahead of a planned A14 expansion. Two years later, after excavations at about 40 sites, they had collected more than 280,000 artifacts.

Of all the tools and bits of bone unearthed, the skull comb stood out. It’s one of only three ever found, worldwide—the other two were discovered at nearby sites decades ago—and was a career first for Marshall, the prehistoric and Roman finds specialist at the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA). It was also an item of intrigue: something that could easily fit in the palm of one’s hand, but which clearly carried great value. Someone had carefully carved nearly a dozen teeth along one edge, and then drilled a hole at the top. Was it a tool? An amulet? Something else entirely? Figuring out the comb’s purpose required understanding how it might have fit into Iron Age Britain.

According to Bangor University archaeologist Kate Waddington, this was a time of big communities living in hilltop settlements called hillforts. “This is very much an agricultural-based society where ritual and religion are deeply embedded within people’s homes and settlements,” she says.

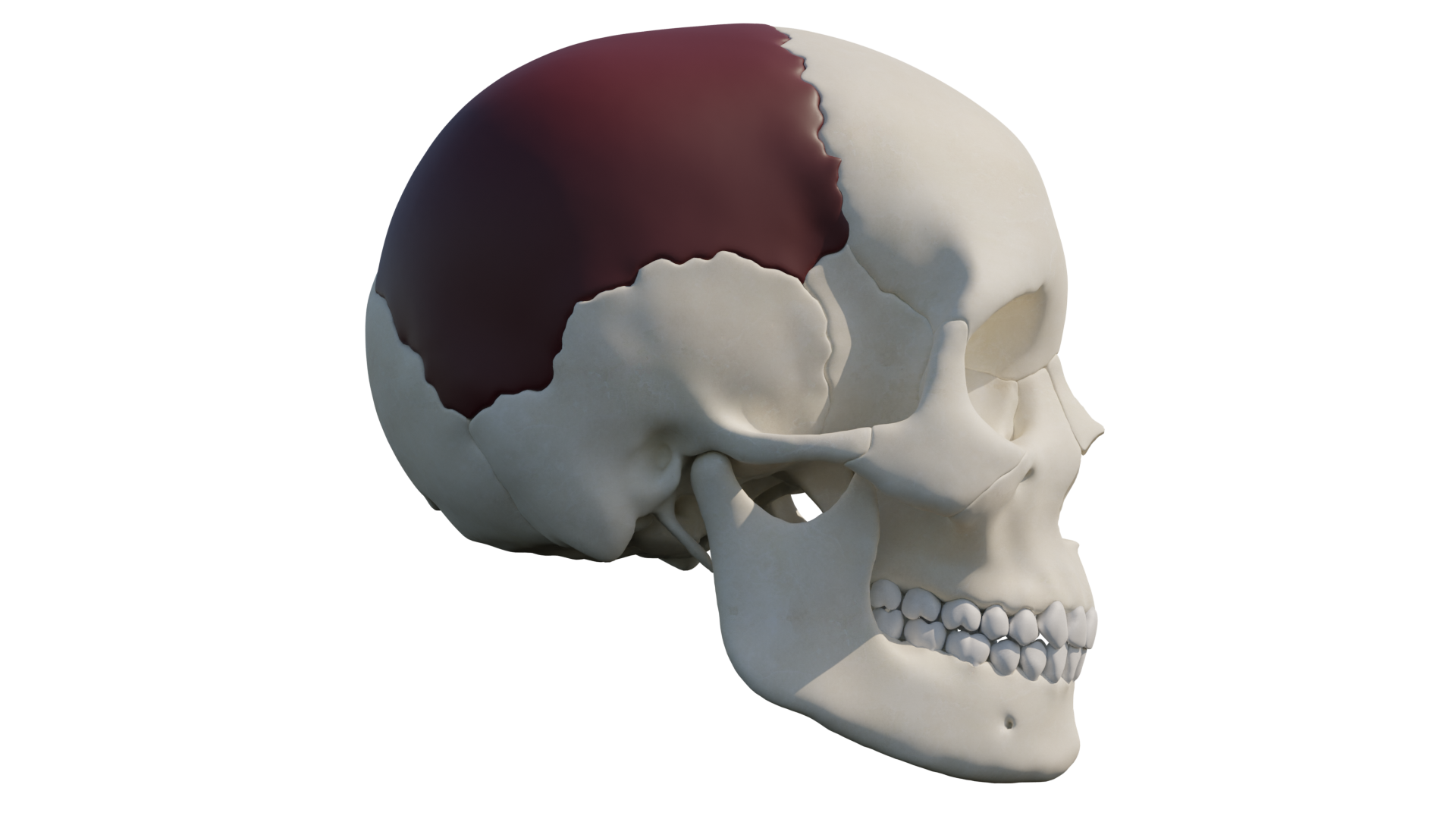

Those rituals included treatment of the dead. According to Waddington, the burial tradition of excarnation was practiced by most Iron Age societies in Britain. “The bodies of the dead are laid out for defleshing, and after the flesh has started to rot away, the bones become disarticulated and you can pick them up,” she says. It appears, however, that only a select few had their bones actually repurposed in some way—most remains, believes Marshall, may have been cremated or dumped in rivers, essentially disappearing from the archaeological record. The discovery of the Bar Hill comb and the two other similar artifacts so geographically close to each other suggests some unique, local tradition, and a particular value attached to the skulls used to create the combs.

In fact, while multiple archaeological finds around Europe show that human limb bones were often used to make various kinds of tools, the human skull seems to have been particularly significant to several Iron Age cultures across the continent. In Southern France, for example, during the Iron Age, warriors would decapitate their enemies and then embalm and display the skulls in front of their homes as a symbol of victory.

“We know that headhunting was a phenomenon in Iron Age Europe,” Marshall says. There’s also, he adds, “a recurrent phenomenon of Iron Age skulls in particular with holes drilled into them.” That includes entire skulls that have several holes drilled at the top; some archaeologists believe the skulls were suspended or hung, says Marshall, “in doorways, rooms, or in a shrine.”

The hole drilled in the Bar Hill comb suggests that it may have been displayed in some symbolic way. The teeth carved into the piece of skull, however, initially suggested another possible—and more practical—function.

“The most unusual thing about the Bar Hill comb that really distinguishes it from the broader context of curated and modified human bones, in Iron Age Britain at least, is the fact that along the bottom edge, it has these sorts of teeth cut into the edge,” Marshall says. The other two skull combs also have teeth, and Marshall first thought it was possible that all three objects were actually used to comb through hair.

“I wondered if it was a sort of ritualized thing, preparation for ceremonies or important events,” Marshall says. Or, he thought, it might have been a way for people to honor ancestors, using the comb for grooming as a symbol of having someone you love looking after you on a daily basis from the afterlife. The comb’s owner may have worn the comb as an amulet, perhaps using the drilled hole to string it like a necklace.

“If you cast around, you can find other examples of this sort of thing,” says Marshall, “things like Victorian mourning jewelry.” Eventually, he concluded it’s unlikely the comb was used for grooming, as its relatively short teeth lack signs of wear consistent with being pulled through hair repeatedly.

There may have been another utilitarian use for the object, he says: as a hide scraper. While it would be a first to find a skull fragment used this way, human limb bones, whittled down for use as tools in hide preparation and leatherworking, have been found at Iron Age sites in the nearby towns of Trumpington and Bedfordshire.

Regardless of how the Bar Hill comb was used, it’s likely that it had some symbolic meaning for the user. Waddington says that the transformation of the skull into a comb-like object reminds her of human skull fragments found at a ceremonial feasting site in Potton, about 20 miles southwest of Bar Hill. The site is a few centuries older than Bar Hill, and the fragments were shaped into small squares. Waddington believes that both the Potton and Bar Hill fragments may have been considered powerful objects linked to the deceased.

The researchers acknowledge we may never know the significance of the Bar Hill comb, or the two similar combs previously found in the area. The full story of these rare combs may have been lost with the communities that made them. “There are lots of little local traditions that distinguish people,” says Melanie Giles, a University of Manchester archaeologist whose research focuses on Iron Age Britain and Northwestern Europe.

Marshall and his team continue to study the Bar Hill comb and other finds from the excavations, looking for clues to regional variability in the ways human remains were treated in the Iron Age. They’re now focused on other human remains found at the A14 site, and hope to extract and analyze ancient DNA from the material. “This might tell us more about mobility within those communities, and may help us get answers,” Marshall says.

While the evidence currently points to the skull combs being a local custom, Marshall believes that, eventually, additional discoveries may connect it with broader traditions throughout Iron Age Europe.

“I think it’s really interesting that this is a recurrent way of treating the dead,” Marshall says. “It’s happened at least three times—and that’s just the times we’ve dug the holes and found them.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook