Before Ellis Island Existed, Castle Garden Welcomed Houdini and Typhoid Mary

How a one-time beer garden became an immigration hub.

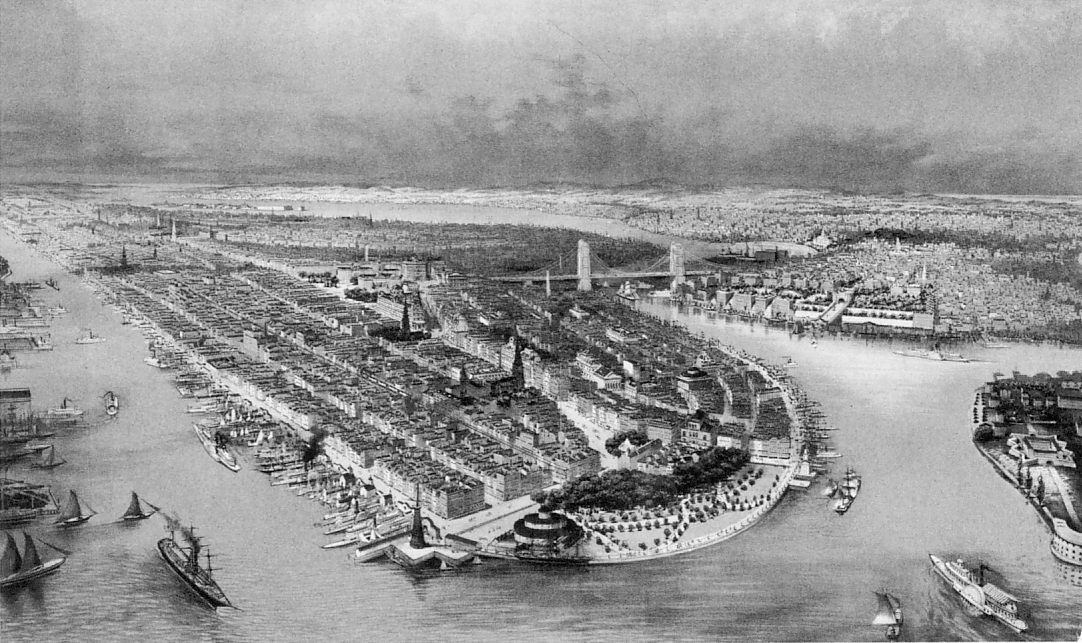

An aerial illustration of Manhattan, showing Castle Garden in the lower foreground, c. 1880. (Photo: Library of Congress)

At the southern tip of Manhattan, thousands of ships packed with hundreds of Europeans, weary from weeks at sea, entered New York’s harbor between 1855 and 1890. New arrivals sat on damp trunks and nursed their children or smoked pipes; city residents from the immigrants’ homelands brought American clothes so their kinsmen could change in the bushes. Unscrupulous tradesmen waited hungrily to take advantage of new arrivals, offering meaningless currency exchange rates, while agents scoped the crowd from the door of the labor office. Horse-drawn carriages carted the immigrants, many from Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Scandinavian countries, to their prospective neighborhoods on the Lower East Side.

But this was decades before Ellis Island, the most famous gateway to life in America, ever opened its doors. Before Ellis Island was built, over eight million immigrants began new lives in America after walking through Castle Garden, a former beer garden and fort turned immigrant safe haven during a time of open immigration to New York City.

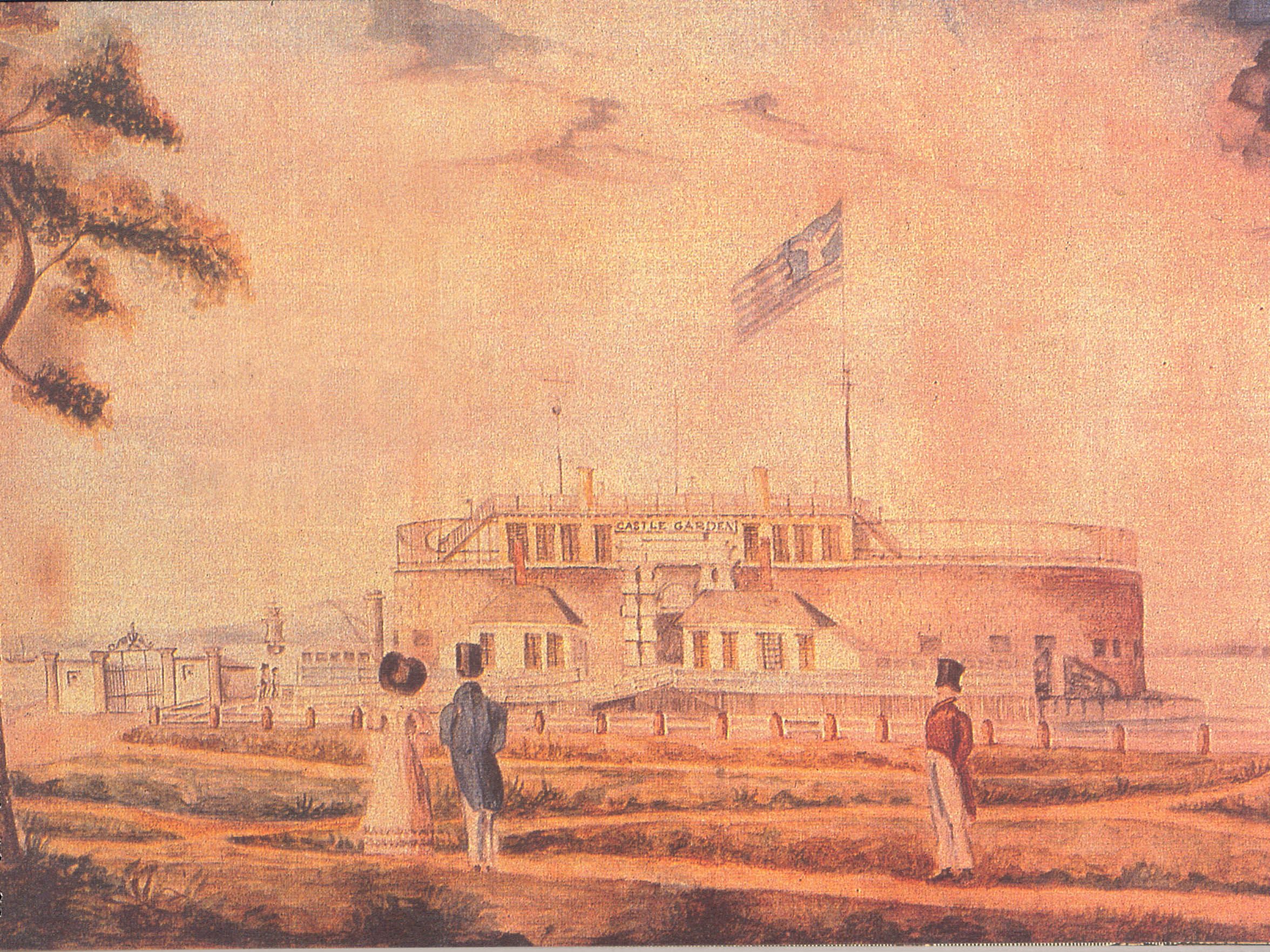

Castle Garden 1825-28, by Alexander Jackson Davis. (Photo: Courtesy of the Battery Conservancy Collection)

Originally called the Southwest Battery, the sandstone fort that is now Castle Clinton National Monument in lower Manhattan was built in preparation for the War of 1812, one of five forts meant to deter the British from the city’s southern waters. However, the British chose to attack other ports instead. Over the following decades, the Southwest Battery took on several new identities. It was briefly named Castle Clinton (after Mayor DeWitt Clinton), and in the 1820s it became Castle Garden, a raucous beer garden, opera house and theater that one New York Daily Tribune article from 1845 says had so many concert-goers that they “tested it to the utmost.”

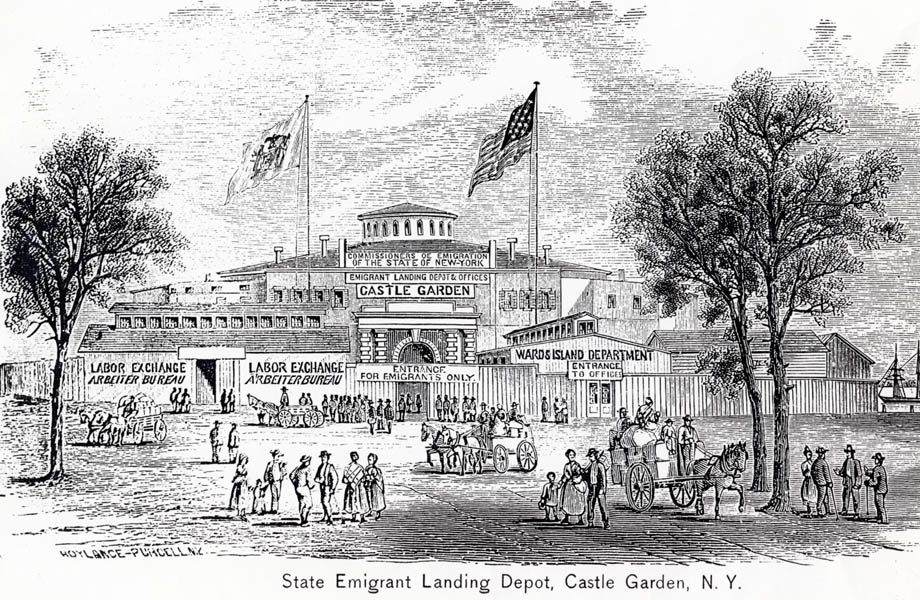

Immigrants started arriving in larger numbers by the 1850s, and New York City needed a more official place for them to go. By August of 1855, Castle Garden had become a state-run immigration portal, and at the time it wasn’t just the main point of entry for immigrants to the U.S., it was the only organized immigration station in the entire country.

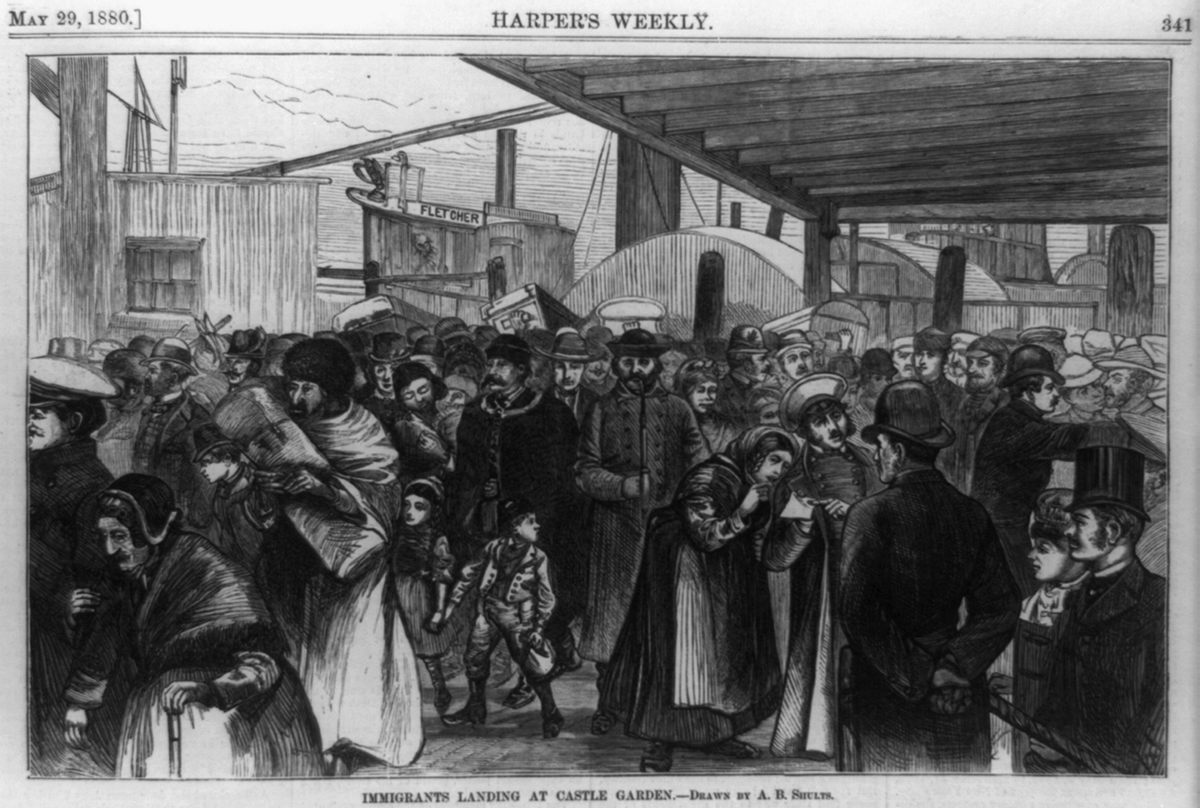

Immigrants arriving at Castle Garden, 1880. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-99403)

Castle Garden, as run by the state government, was intended as part of a new effort to track disease, and give immigrants a place to convene before going onto to their new, confusing lives.

Still, people who arrived through Castle Garden found themselves in a disorienting hodgepodge of people, beckoning them in multiple directions. This was so much the norm that the Yiddish noun kesselgarten, which means “disorder and chaos”, comes directly from a pronunciation of Castle Garden.

“As much as we were trying to safeguard the immigrants’ interests, [New York residents] were taking advantage of the immigrants who did not know the language,” says Warrie Price, the founder and President of the Battery Conservancy, which maintains the park where the former Castle Garden stands. Con artists often sold new immigrant families train tickets for imaginary trains, naturally giving them terrible exchange rates for their foreign money.

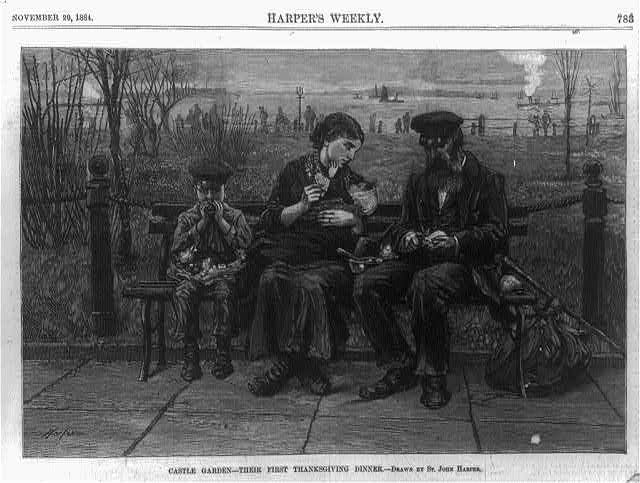

Their First Thanksgiving Dinner, from an 1884 issue of Harper’s Weekly. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-99401)

Local aid programs popped up around the bustling port; a nearby church set up classes to teach young Irish women to be housemaids, and immigrant aid groups waited for new arrivals to guide them safely around opportunists who hoped to take advantage of them, and on to neighborhoods where their languages were spoken, and jobs. Thanks to the open immigration policy, there were no visas, health checks, or governmental red tape to navigate; if you made it to New York, you got to stay.

“Many people, because we were in the middle of the Civil War during this period, went right into the Union forces,” Price says. “We had a Union group of people that would sign you up—we’ll feed you, we’ll cloth you, sign here.”

Of the approximately eight million people who sailed into New York’s first immigration port between 1855 and 1890, an enormous amount settled down in New York City. Ninety-seven percent of Irish immigrants stayed in the city, forever changing its culture and heritage; Emigrant Savings Bank near Grand Central station was established by Irish immigrants who came through Castle Garden.

Castle Garden in 1853. By 1855, it was a government-run immigration portal. (Photo: Courtesy of the Battery Conservancy Collection)

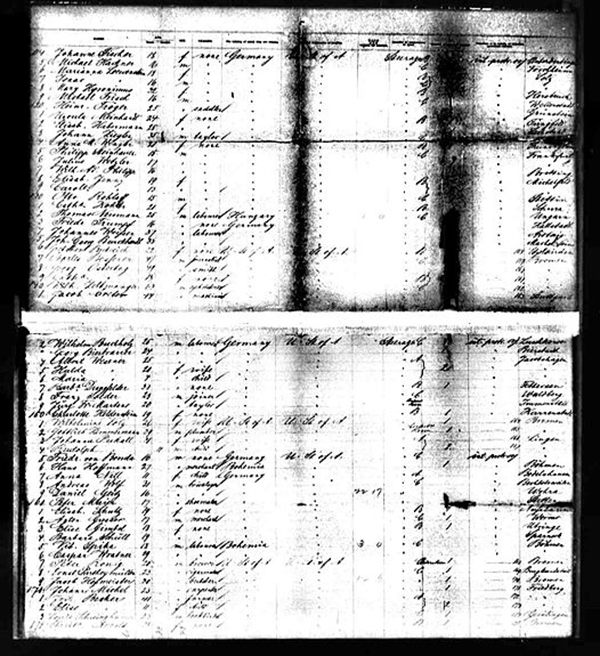

Others became permanent fixtures in American culture. Mary Mallon, later known as “Typhoid Mary”, first walked off of a ship from Ireland into Castle Garden in 1883 at the age of 15; Nikola Tesla’s first steps on U.S. soil took place the next year, and Harry Houdini, Emma Goldman, and Joseph Pulitzer all began their lives in America the same way. In 1885, a 16-year-old runaway barber from Germany named Friedrich Trumpf came ashore at Castle Garden, and began to build the real estate empire later inherited by his grandson, Donald Trump.

By 1890, New York City had grown to 1,515,301 inhabitants, up considerably from the 629,904 residents of 1855. A similar population swell around the United States gave the government pause, and federal agencies stepped in to regulate the burgeoning immigrant population. In 1890, Castle Garden was closed and immigrants were accepted at the Barge Office, where the New York Coast Guard is today, until Ellis Island was finally built and put to more permanent use.

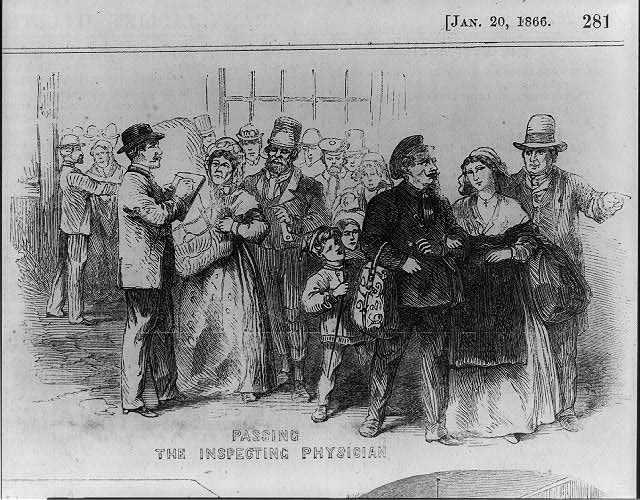

Immigrants at Castle Garden with the inspecting physician. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-37828)

Ellis Island’s service dwarfed Castle Garden in subsequent years, and completely changed the way New York dealt with immigration. Up until this point, immigrant workers were welcomed, no questions asked. While very ill immigrants who arrived at Castle Garden were taken to hospitals until they were well, immigrants on Ellis Island were pre-screened for possible health issues, and could be quarantined at the gate.

If you were a little too winded when running up and down stairs, as part the health exam, “they would put an “H” on your [armband], meaning you might have a heart condition,” says Price. You could be sent back home if you didn’t pass some medical examinations. Information on new potential citizens was recorded and stored centrally; the days of open-door immigration was over.

A postcard from 1917, showing the aquarium and Battery Park. (Photo: Courtesy of the Battery Conservancy Collection)

In 1896 Castle Garden reopened as New York’s first municipal aquarium, and the building was expanded considerably. A Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine article from 1897 describes it having a 20,000-square-foot building with “graceful archways”, a glass-paned roof, and tanks surrounded by plants and shrubs where “his majesty, the whale, swims and blows as only whales can; a rookery for the sea-lion, and a pond for the seals, complete the central view.” The aquarium’s marine life and education programs lured an average of 5,000 people per day, but in the 1940s, a full 130 years after it was built for war, it became part of a heated battle.

In 1941, the powerful New York City parks commissioner Robert Moses pushed to build a new bridge from Brooklyn into the city, creating a public outcry. Preservationists of the time believed a bridge would ruin the residential park in the Battery Park City neighborhood where Castle Garden had flourished, and with the help of President Roosevelt, fought for a tunnel instead.

When they won, Robert Moses was obliged to move the aquarium to Coney Island—but he didn’t just move the sea life, he decided to dismantle the building. Bit by bit the glass roof, decorative lighting and ornate second floors were ripped away.

The ‘State Emigrant Landing Depot’ at Castle Garden, 1870. (Photo: Courtesy of the Battery Conservancy Collection)

A group of preservationists stepped in again, and stopped Moses from destroying the original walls of the fort; Congress declared it a national monument in 1946. “It was one of the first successful preservation fights in New York, the saving of the original brownstone walls of the West Battery,” says Price. In the 1970s, the monument was restored to its original form as a military fort.

Until recently, finding records of people who were received at Castle Garden was a challenge. Many of the ship manifests from New York immigration vessels were burned in a fire on Ellis Island in 1897, and while some records survived, they lay dormant in Temple University and the National Archives for years. For the 150th anniversary of Castle Garden’s time as an immigrant entry-point, the Battery Conservancy coordinated the digital transcription of the documents previously held at Temple University.

The immigration records from 1885 that shows, on line 33,”Friedr. Trumpf” - grandfather to Donald. (Photo: US Government/Public Domain)

It’s possible that some of those records did not survive the ages or that the online archives aren’t yet complete, as names of specific passengers and families processed at Castle Garden are still difficult to track down. If you’re interested in looking for records from Castle Garden, you can search the Battery’s store of digital copies at castlegarden.org, or see them firsthand at the National Archives. The genealogical websites stevemorse.org and immigrantships.net also have searchable manifests from Castle Garden’s immigrant vessels.

What once was Castle Garden still greets visitors to Battery Park City; its protective walls still rise into the air at the edge of the sea. Now attended to by the National Park Service as the Castle Clinton National Monument, the structure is surrounded with plaques and an actual garden, part of a major revitalization project run by the Battery Conservancy. It now hosts everything from urban farms to a trippy carousel with fish-shaped fiberglass seats.

“The Battery always adapted to the needs of New York, and it’s very much reflected of the lives of the Castle. The park changed to really respond to the needs of the citizens,” Price says. “I think that’s the interesting thing about the Battery—it’s seen the footsteps of all of our history, and we hope it will continue to do that.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook