The Tricky Business of Saving a Baby Beluga

For the first time, scientists were able to save a young whale stranded in Cook Inlet. What should happen next?

It was an unusually calm day in Cook Inlet, Alaska, on September 30, 2017, when Carrie Goertz got a call that made her heart sink: a baby beluga whale was stranded on a nearby mudflat. Noah Meisenheimer, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) officer, had spotted the calf from a helicopter. At first, he thought it was already dead. The body was in just a few inches of water, getting tossed around by the surf. But then, Meisenheimer saw the calf move. Immediately the helicopter touched down. Meisenheimer tried to push the struggling whale back into the inlet. Again and again, he tried, but each time the current would pull the desperate calf, gasping for air and inhaling water, back onto the mudflat. That’s when Meisenheimer called Goertz, director of animal health at the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward, Alaska. Goertz was nearby cleaning up from an unrelated whale autopsy. The helicopter was already on its way to pick her up and when she landed, she would have to decide whether to try to nurse the calf back to health or to humanely euthanize him.

No one had ever successfully rehabilitated a stranded beluga calf. Goertz knew that all too well. In June 2012 she had been part of the team that had tried to save Naknek, a baby whale that washed up after severe storms near South Naknek, Alaska. That calf, named after the Inuit community he was found near, died three weeks after his rescue. But this calf was larger and older than Naknek, and he didn’t seem to have any severe injuries. So Goertz decided to attempt the impossible again.

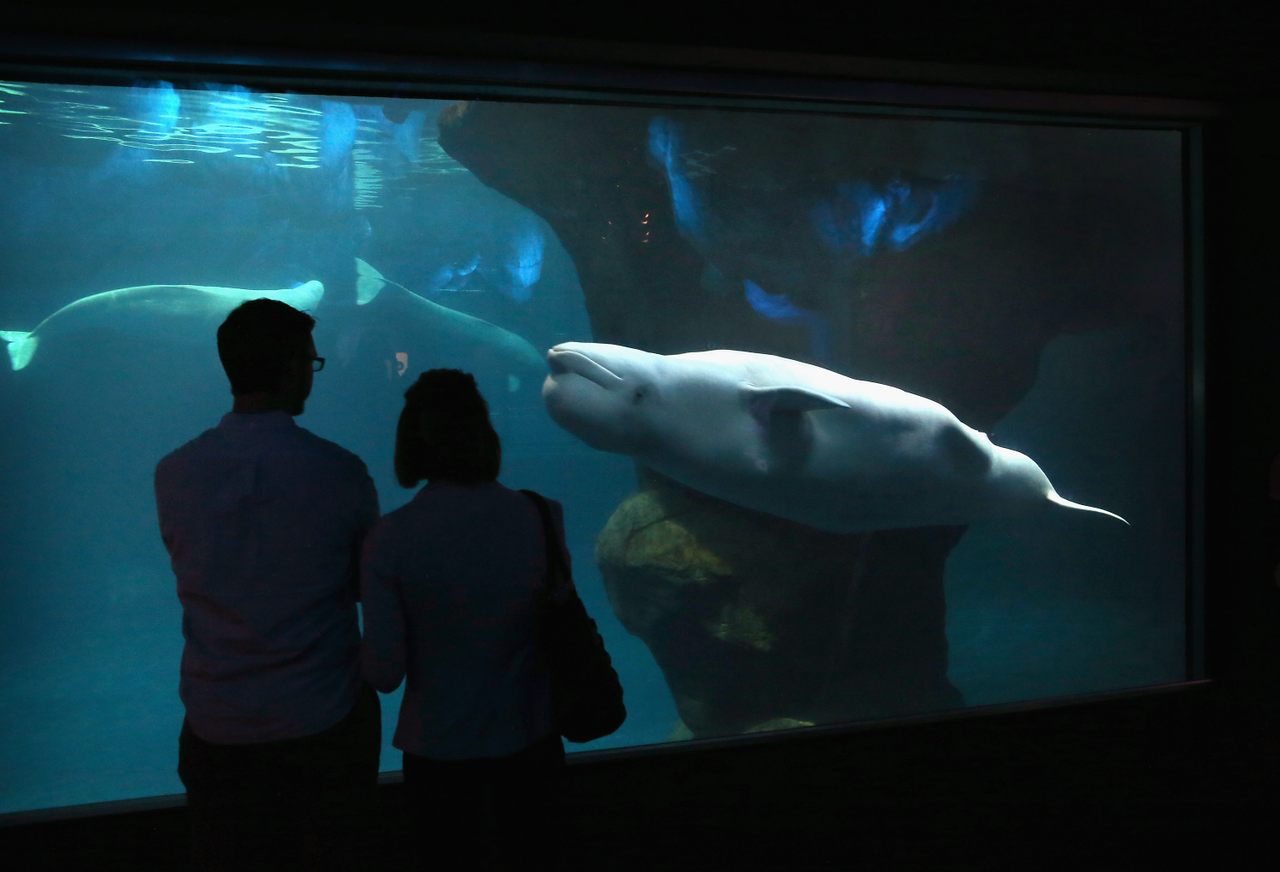

Today, Tyonek—who was also named for the Indigenous community he was found near—is alive and well, swimming alongside 11 other belugas at SeaWorld San Antonio. He is one of only 300 belugas from the critically endangered Cook Inlet population, and the only one living in captivity.

Naknek and Tyonek’s stories began quite similarly. It was a mild mid-afternoon when beach walkers came upon Naknek on June 18, 2012. Violent storms from the previous night had likely separated Naknek from his mother. There were no adult belugas seen nearby, and it quickly became clear that Naknek would need human veterinary care and rehabilitation to survive. That’s when Goertz and the Alaska SeaLife Center stepped in.

They flew Naknek 300 miles to the center, disrupting flight schedules in the process. When he arrived, the whale was placed in a 20-foot-diameter indoor pool and received around-the-clock care from ASLC and a team of beluga experts from around the country. He was tube-fed an artificial formula packed with ground herring, salmon oil, and nutrients that had been found in milk samples from nursing aquarium belugas. He didn’t seem to know how to suckle, something the two-day-old calf was probably only just learning how to do in the wild.

At first, Naknek seemed to be improving. He was gaining weight and becoming more playful. But a couple of weeks into his rehabilitation, Naknek started to deteriorate. He became increasingly disoriented, developed breathing issues, and ultimately died on July 8, 2012, 20 days after his rescue.

Fast forward five years and it was Tyonek’s turn to be airlifted to the center. Using life jackets and wet cloths, Goertz, Meisenheimer, and others were just able to fit the five-foot-long calf into the State Trooper helicopter that had taken them out that day. “It was definitely a MacGyver situation,” remembers Goertz.

When he finally arrived at the center, it was clear Tyonek was in worse shape than Naknek had been. Tyonek couldn’t even swim around the pool when he arrived and spent his first few days in a sling.

“It was a pretty intense several months,” says Goertz. At one point, Tyonek’s lung collapsed—something he eventually recovered from without treatment. There were concerns about him developing severe illnesses. But as the weeks went on, Tyonek started to improve. He was older than Naknek when he was found, at about 16 days old, and he had the advantage of having gotten crucial antibodies from his mother’s milk that likely aided in his recovery. He learned to bottle feed and slowly became more self-sufficient.

By week five, Tyonek was strong enough to move into a larger, outdoor pool. Susan Allen, a marine mammal supervisor at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, remembers just how playful the calf had become. “He was very interactive. I remember distinctly being in the water and bringing in some enrichment to play with him,” she says. “He would just kind of push along the toys and push me along in the water too.”

NOAA, which oversaw both Naknek and Tyonek’s care, eventually deemed Tyonek non-releasable, because of his reliance on human care. A call went out to aquariums around the country to volunteer to take in Tyonek. In the end, NOAA deemed SeaWorld San Antonio the “location best suited for Tyonek to thrive.” “It’s a great place for him,” says Goertz, with “lots of different belugas for him to get to know [and] a nice large facility.”

To help with future rescues, Goertz recently published a paper in Polar Research comparing Tyonek’s rehabilitation with Naknek’s. The detailed case study provides researchers with a roadmap to use in caring for young beluga whales.

Bill Van Bonn, vice president of animal health at Shedd Aquarium and co-author of the new study, says researchers don’t know definitively why Naknek didn’t make it. It’s “very likely that his immune system was not functional,” says Van Bonn. “Mammals need to nurse to get a lot of their antibodies from their mom and immune components, and it may very well be that he didn’t get enough of that.”

Naknek’s survival taught scientists a lot about rehabilitating a beluga whale calf. But an even bigger question looms: Should belugas like Tyonek be in captivity? Vann Boon believes that belugas—unlike some whales—can thrive in an aquarium setting, but other scientists believe it is unethical to have such intelligent animals in tanks. Whale researcher Dave Duffus from the University of Victoria would have chosen not to remove Tyonek from the beach, knowing it would’ve led to a lifetime in captivity. In an interview with CBC, he said, “I’d prefer to see animals live their lives and die in the natural ecosystems that they’re part of.”

But anti-captivity, cetacean behavior expert Lori Marino is glad little Tyonek was rescued: “where there’s life there’s hope.” And soon, thanks to Marino, the founder and president of the Whale Sanctuary Project, there will be an alternative to a life spent in a tank for whales who need human care. The Whale Sanctuary is a 100-acre, seaside sanctuary set to be completed in 2023, where whales will be able to interact with other sea life, like fish, birds, and crabs. They’ll be able to dive and explore with other belugas, says Marino, and most importantly they won’t be asked to perform or be on exhibition for visitors. While the whales will still need to be trained to comply with regular veterinary appointments and feedings, Marino says the importance of the sanctuary is in how it changes a visitor’s perception. Rather than whales being an attraction, here “it’s all about them.”

In the five years since his rescue, Tyonek seems to have adjusted to life in San Antonio. He’s even formed what SeaWorld animal care specialist Katie Kolodziej called “an indescribable and unbelievable bond” with a dolphin named Betty. Tyonek’s 4,000-mile journey from a mudflat in Cook Inlet to an aquarium in San Antonio proves that beluga whale calves can be successfully rehabilitated—something long thought to be impossible. For Van Bonn, rehabilitating animals like Tyonek is humanity’s “obligation.” “It doesn’t matter if it’s one of these pajama cardinalfish or a beluga,” says Van Bonn, “we have an obligation to every kind of animal to understand them and take care of them.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook