Revisiting Detroit’s Black Bottom Neighborhood, Decades After Demolition

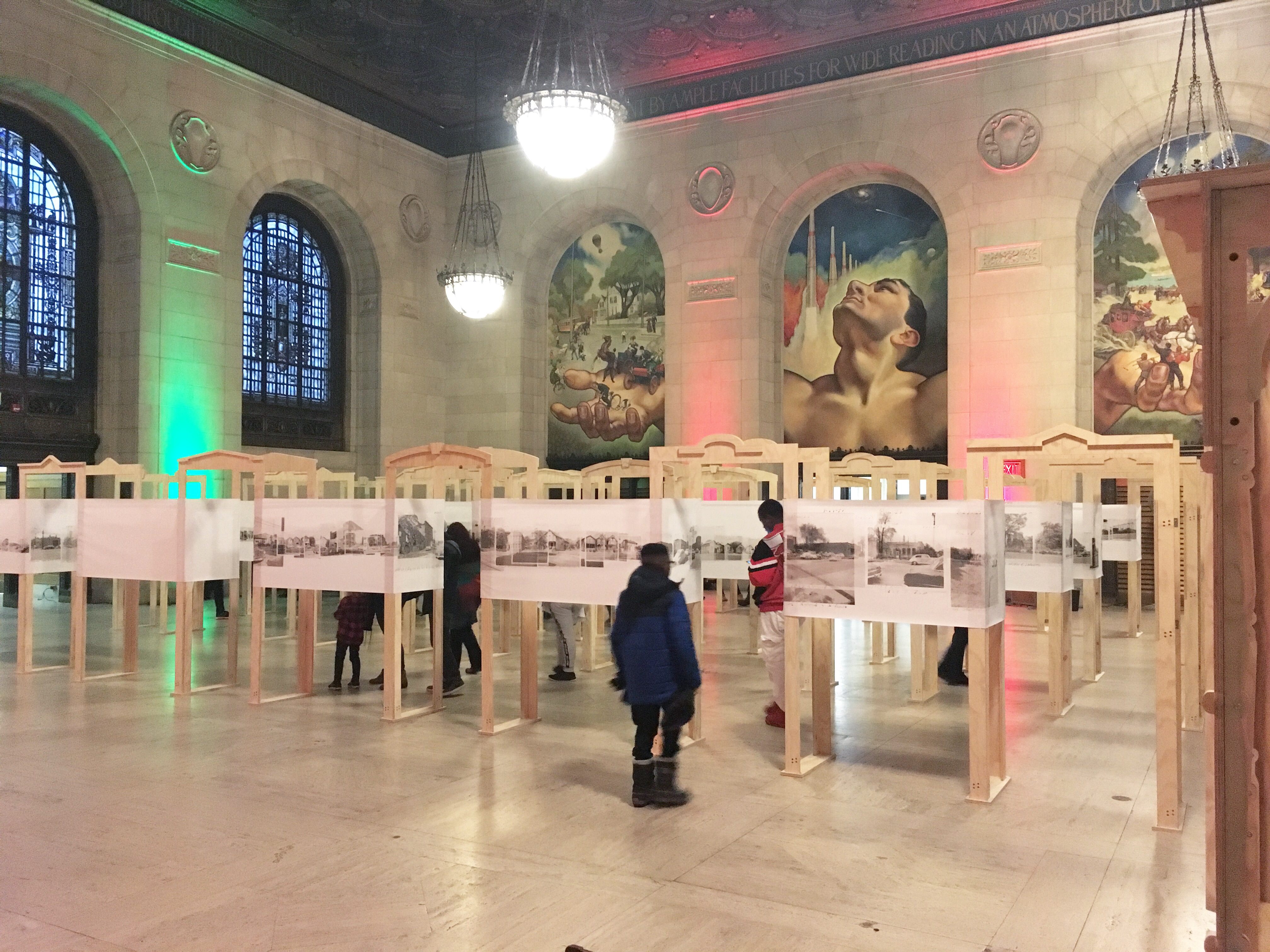

A new installation at the Detroit Public Library conjures a lost community.

The plywood frames are skinny and shallow, like the featherweight facades of a stage set. Look closely at one, and the next, and the next, and the shapes of windows and doors will appear. Over time, they begin to conjure a block, and then a whole neighborhood.

Inside the main branch of the Detroit Public Library, visitors can now walk through a photo installation that recreates the streets of Black Bottom, a Detroit community that was razed more than half a century ago. The plywood frames, part of the Black Bottom Street View project, on view through March 2019, occupy almost all of the library’s soaring Strohm Hall and are laid out to recall the street grid of the old neighborhood. For the exhibition, Emily Kutil—an architect and scholar at the University of Detroit Mercy—wrapped the frames with layered photographic montages of the streets as they appeared in 1950, just before the neighborhood was dismantled. The result evokes the sensation of strolling through the community house by house, paying tribute to a place that has left few other traces on the landscape.

Before Black Bottom became one of the first U.S. neighborhoods knocked down in the name of midcentury urban renewal, with funding from the Federal Housing Act of 1949, it was full of people, of homes and cars, lawns and porches. In the early 20th century, Detroit’s African-American population swelled as families streamed out of the Jim Crow–era South. Between 1910 and 1940, the city’s black population climbed by more than 34 percentage points.

Many of these newcomers settled in Black Bottom, where races and socioeconomic classes mingled. “Black people lived here, yes, but so did immigrants from Ireland, Poland, Greece,” says Jamon Jordan, a historian who leads tours of the area. “In the teens, 20s, and 30s, you had a black doctor living next to a family that had just arrived in the city,” Kutil says. (Coleman Young, who would go on to be the city’s first black mayor, moved there from Alabama as a young child.) Some say the neighborhood’s name was a nod to its dark, fertile, soil, while others suggest that it was a snide comment about the demographics of its residents. “In its heyday, it was a thriving African-American community,” Kutil says, “in a time when the forces that be were doing their darnedest to prevent the African-American community from thriving.” Though the neighborhood’s struggles are well documented—overcrowding, absentee landlords, and some dilapidated buildings—Black Bottom was vibrant.

After World War II, city leaders came to see the neighborhood as a bad thing for the city, and officials laid out an economic case for destroying it, estimating that, after redevelopment, the value of the land and new buildings would soar by 725 percent. With Federal Housing Act funding in hand, officials moved forward with eminent domain. When wrecking crews leveled the existing homes and businesses beginning in the 1950s, in the name of removing a blight on the city, many residents viewed the project more as a way to eject and stunt the black community.

The city government offered a little more than $6 million in total to buy up the land. As part of the eminent domain process, officials photographed each parcel, and every image was labeled with the address and date. Civic organizations, shops, and churches had flourished alongside the homes, and some of the houses of worship are still standing on the distant edges of the historic neighborhood. Closer to the core, almost nothing was spared, Jordan says. “Most of the institutions that were in the center, no matter what religious group or culture, they’re gone.”

After residents were removed and buildings demolished, the area sat fallow for a few years—Kutil says locals recall vacant land dotted with handsome old trees and roamed by feral dogs—before new roads were laid down and high-rise housing built up. Ultimately, the neighborhood was replaced with the Chrysler Freeway and a slew of new buildings that went up in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, including Lafayette Park, a cluster of mixed-density housing designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Now, “everything in that area is post–Black Bottom,” Jordan says.

Decades later, boxes of these Black Bottom photos, other eminent domain documents, and more were found in library storage, and then digitized by the Burton Historical Collection, where researchers recognized the materials as an accidental archive of a neighborhood’s final days. The pictures that remain only account for about one-fifth of the homes that once stood in the community, Kutil says. But cataloging, digitizing, and mounting them “is like bringing to life the Lost City of Atlantis,” local writer and activist known as Marsha Music recently told the Detroit Free Press. Kutil, who also does activist work around current development projects in Detroit, initially planned to draw the neighborhood and stitch her sketches together. But then she realized the potency of the photographs, as a true visual account of the yards, the balconies, the faces.

Though the neighborhood’s physical traces are largely gone, its legacy remains. Many people with deep roots in the city can trace their families back to Black Bottom, and commemorate the vanished neighborhood in art or exhibitions. When Jordan’s tour groups visit the former neighborhood, they juxtapose information about the past with realities of the present and try to grapple with the gulf between the two.

Plans are also now in the works for a historic plaque to pay tribute to Black Bottom. When a team at the Michigan History Center, which triages applications for such historic markers, read through the application, they thought, “Well duh, yeah, it’s significant!” says Tobi Voigt, the community engagement director, who previously worked at the Detroit Historical Society. At the same time, the group thought that “a marker for a community this big shouldn’t be created by a commission or one applicant,” Voigt says. So they convened a discussion with the Michigan Historical Commission, the Detroit Historical Society’s Black Historic Sites Committee, and residents, to gather personal stories and start to figure out where the marker ought to go and what it should say. “We’ve got 1,000 characters,” Voigt says. “We have to sum up 150 years of history in two paragraphs.”

Talking to community members, Voigt says, she realized that the marker alone—which will join 1,700 others across the state, on everything from lighthouses to relics of the timber industry—felt like a tangible validation. “It’s a symbol that ‘My story matters,’” Voigt says, even if the footprint of the community is long gone. While conversations are ongoing, both Voigt and Jordan, who is active in the discussions, are optimistic that it will go up in the next year or so.

Meanwhile, Kutil hopes that the Black Bottom Street View installation—and future iterations, including a website made in partnership with the Black Bottom Archives, where people will be able to contribute personal histories—will be useful for both old timers and people who don’t have a direct connection with the neighborhood. For those who remember growing up there, Kutil says, “it can be kind of cathartic to put yourself in that place again.” Outsiders “may have a skewed conception of what it is,” she adds, “and still talk about it as though it was a terrible place that needed to get destroyed. I hope it myth-busts some of that, too.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook