When Trippy Black-Light Murals Brought the Cosmos Down to Earth

The paintings once dazzled and enlightened mid-century planetarium-goers.

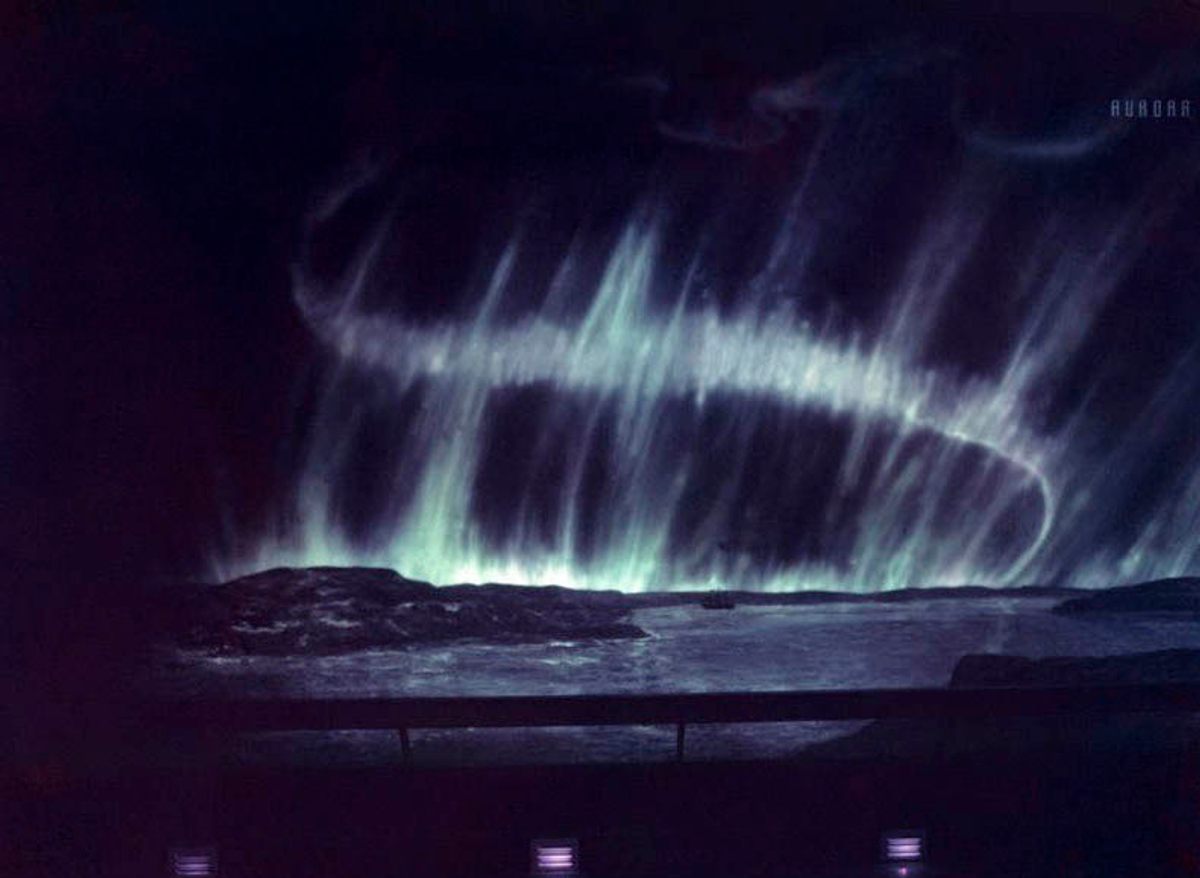

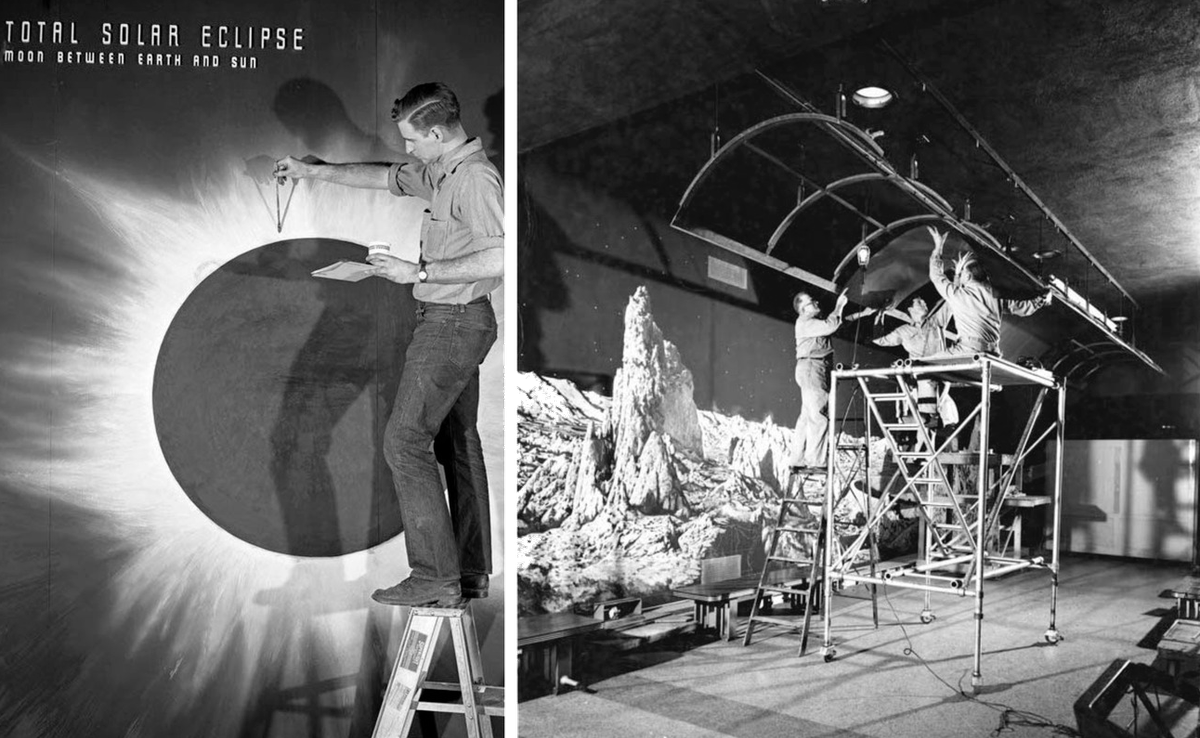

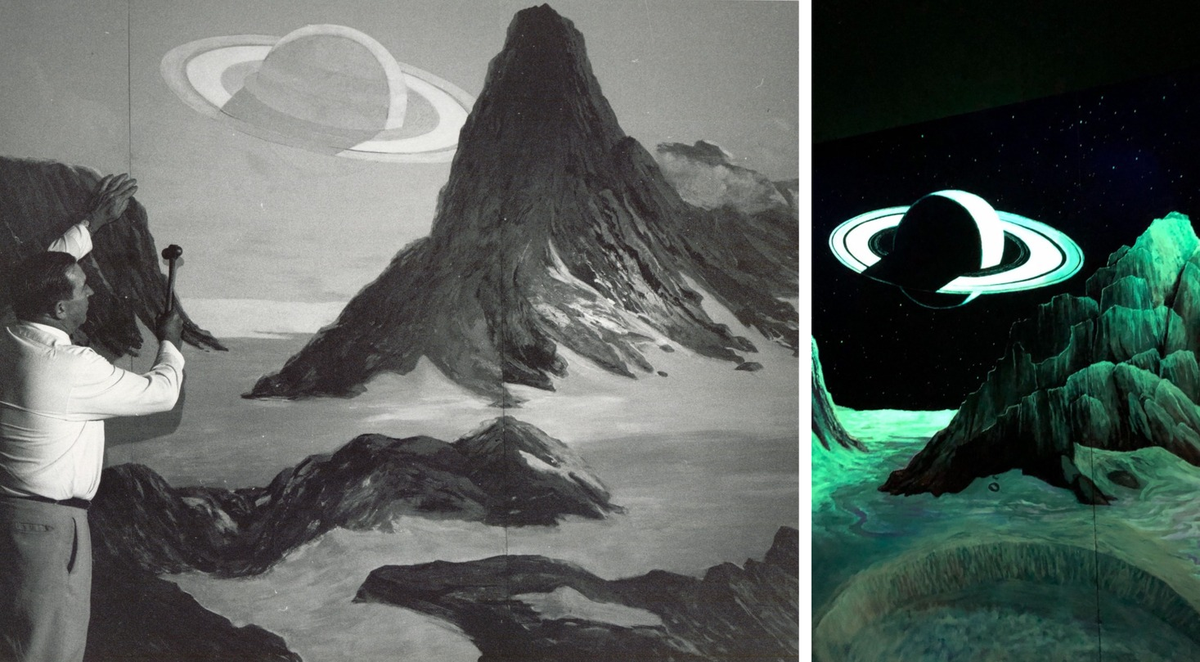

One day in the 1950s, Thomas Voter pulled a mask over his nose and mouth, reached for an airbrush, and attempted to make the aurora borealis dance across a darkened sky. The particular paint he was using contained ingredients that would fluoresce under ultraviolet light, also known as black light. These lights near the mural would be designed to sweep across the image, making the aurora shimmy, quiver, and astound.

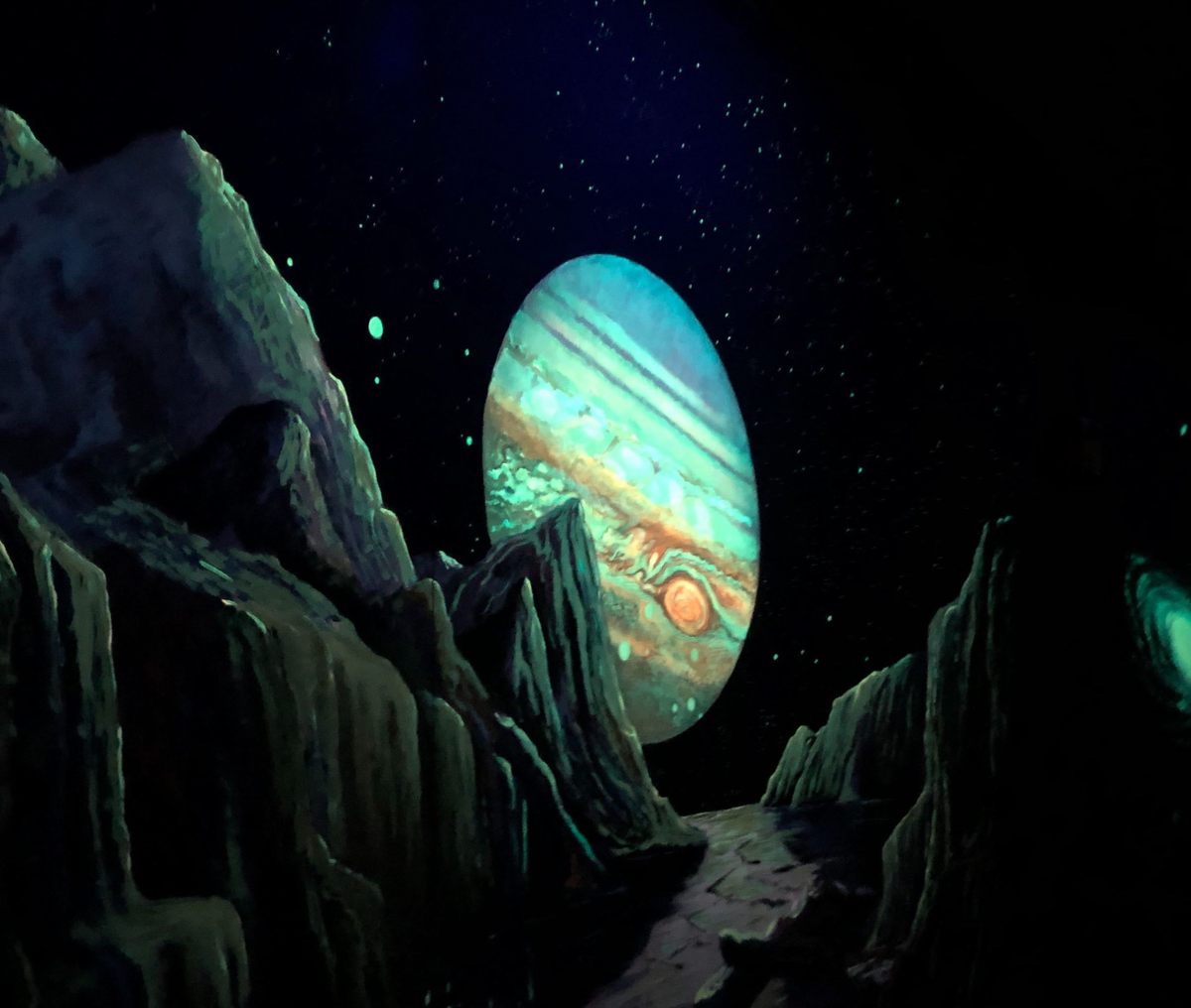

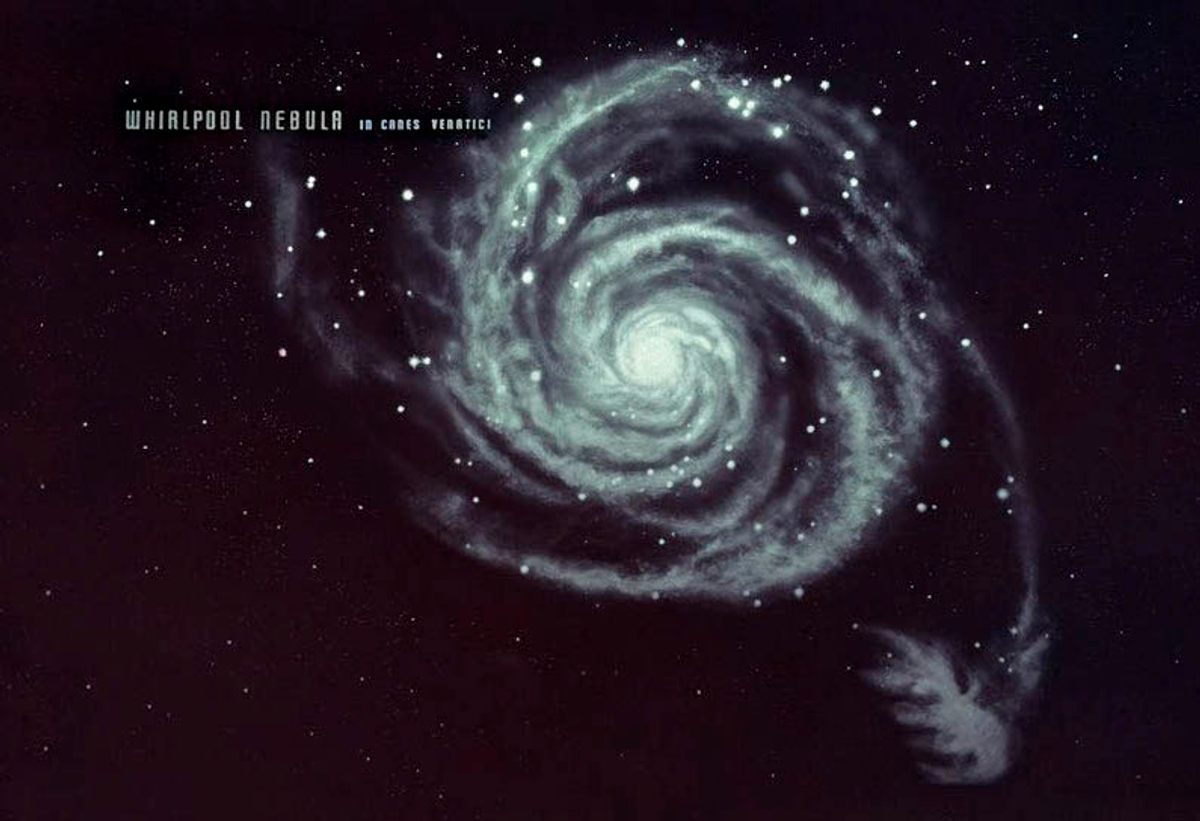

Along with his team, Voter, an artist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, was finalizing 14 astronomical murals for the first floor of the museum’s Hayden Planetarium. Long before scientists could use reams of data to digitally reconstruct planetary surfaces or send someone virtually soaring through a distant constellation, these paintings were mainly based on photographs, drawings, and written reports. They depicted, among other things, Mars, Saturn, the 1833 Leonid meteor shower, the Horsehead Nebula, and a solar eclipse, Sky and Telescope reported in May 1953. The murals’ designer, Joseph M. Guerry, told the magazine that the fluorescent-paint technique was “like painting with fire.”

The Hayden’s black-light gallery debuted in the ’50s, “before the hippies figured out they had something to get stoned to,” says Carter Emmart, now the museum’s director of astrovisualization. A space nerd since a toddler-age trip to the futuristic 1964 World’s Fair, Emmart began taking classes at the planetarium at age 10, by which time rock bands and poster-makers had embraced the black-light aesthetic, leading to its long association with psychedelics. The young Emmart found himself especially mesmerized by the lyrical mural of the Horsehead Nebula, which sits on the belt of the constellation Orion. “I lusted after getting a black light, but mainly I was interested in astronomy,” he says. “I wanted to have my own black-light hall in my room at home.”

It was the heyday of black-light galleries in planetariums across America. The space race was heating up, and the time saw a boom in “space art.” In her book Destined for the Stars: Faith, the Future, and the Final Frontier, University of Miami historian Catherine Newell traces the work of Chesley Bonestell, a godfather of modern space art, back to the longer tradition of swoon-worthy-but-relatively-accurate landscape art. Bonestell’s paintings have the feel futuristic versions of New Deal–era posters of America’s National Parks, with sweeping vistas and craggy rock formations. Bonestell’s work “sells a vision of outer space not necessarily as utopic, but as the natural next step humanity was going to take,” Newell says. Newell sees obvious traces of Bonestell’s artistic DNA in the black-light paintings that appeared in the Hayden and beyond—they all encouraged viewers to get excited about discovery, exploration, and a future among the stars.

There’s no formal tally of how many planetariums once had these fluorescent illustrations, says Mike Smail, director of theaters and digital experience at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium (which didn’t have one). Even without an official roster, he adds, it’s clear that they weren’t uncommon. Black-light murals were “a weird little niche,” Smail says, “and big and small places started doing it.” In the United States, they decorated planetarium walls from New York to Texas to Florida. The Manitoba Museum, in Winnipeg, Canada, had black-light art, too. “There’s always a lot of cross-pollination of ideas,” Smail says, and it’s likely that these displays were mentioned and discussed at conferences for the planetarium community. Staff from across the planetarium world may have swapped tips, or even artists; a decade after Voter painted the scenes at the Hayden, he also signed his name on the ones at the Abrams Planetarium at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan.

For planetariums, which traffic in education, hard data, and slack-jawed awe, black-light galleries “just made sense,” Emmart says. Nebulae and galaxies, in particular, practically begged to be painted this way, massive and bright, immersive and attention-snaring. And, Emmart adds, they were a little bit magical.

These galleries also often served a practical purpose. Planetariums have to be dark, and black-light galleries gave guests something to look at while they wandered through “light-lock corridors,” the spaces between the bright light outside and the darkened dome of the planetarium itself. At the time, star projectors were dimmer, says John French, the production coordinator at the Abrams Planetarium, and it could take visitors’ eyes 15 or 20 minutes to adjust enough that they could fully appreciate the details they were about to see.

Black-light murals also took a cue from the panoramas that provide the backgrounds to many of the animal dioramas in natural history museums. The painters of those murals sometimes journeyed to the locations they were depicting to be sure they were faithfully capturing the setting and the quality of light. The artists working on space murals weren’t trekking to Mars, but they were similarly “sensitive to the details,” Emmart says. The painting of the Horsehead Nebula, for example, included the subtle gradations in the colors of the clouds of hydrogen gas and dust.

The image of the Horsehead Nebula, like the rest of the Hayden’s black-light murals, came off display in the late 1990s, when the planetarium was renovated and modernized. The Hayden is now inside the Rose Center for Earth and Space, which opened in 2000, and the paintings are in storage. While they were on view, though, they were transportive.

The black-light murals that have been preserved—mostly in photographs, though some survive—are time capsules of the state of scientific knowledge at the time they were made. In the 1950s, scientists could only see Mars through telescopes, says Emmart, and that meant that Earth’s atmosphere was always in the way. “It’s sort of like looking down a road on a hot day,” Emmart says. “Air is in motion, so you have a mirage or a distortion.” The planet’s polar ice caps were discernible, so those made it into Hayden’s mural, but many other fine-grain details that we know today hadn’t yet come into view.

Sometimes the murals needed to be revised, too. Between 2010 and 2012, when she was a senior planetarium educator and staff artist at the Edwin Clark Schouweiler Memorial Planetarium at the University of St. Francis in Indiana, Jackie Baughman “fixed some anatomy issues” on the mural depicting the constellations of the zodiac. Scorpio looked more like a crayfish, and Pisces had some issues, too. The orange liquid spewing from the fishes’ mouths was supposed to be water, but “every child who walked by thought they were puking,” she says. Changes sometimes followed space missions. After the Voyager spacecraft approached Jupiter and Saturn in the 1970s and ’80s, “we had much better ideas of what they looked like, and repainted those planets to give them more of an updated look,” says French, of the Abrams Planetarium. And the rocks were scaled back in the Saturn mural to provide a clearer view of the rings.

Broadly speaking, black-light murals “were popular until the late ‘90s, and then digital technology took over,” Smail says. Planetarium projectors grew brighter, so visitors didn’t have as much time to kill while they waited for their eyes to adjust, and some planetarium staffers were probably happy to trade nostalgia, which sometimes veered toward the charmingly gaudy, for more cutting-edge stuff. Now there are fewer murals and more screens, and the images on them are generated by precise data. “Robots have sent back so much data that we can effectively create Mars in front of you in motion, and move about it,” Emmart says. Smail adds that it’s much easier to update a database or computer program than it is to repaint a mural: “We can add a new comet or planet to our system and have it up on our dome in a matter of hours.”

As a result, many black-light galleries have vanished. Some of the paintings have been discarded, or donated to other institutions. The mural Baughman worked on was lost a few years back, when the building was demolished. Still others went into storage, like the Hayden’s. But a few other planetariums, such as the Ho Tung Visualization Lab at Colgate University, are relatively new to the black-light game. Their mural has only been around for a little over a decade. The Abrams Planetarium in Michigan still displays its examples, and a few years ago even repainted the faded black walls to make the murals pop once again. Though black-light paintings aren’t as alien as they once were when Emmart first saw them, they still have the capacity to amaze.

French gets a front-row seat to the wonder when he runs the planetarium Show at the Abrams. Before he does his velvet-voiced spiel—sometimes accompanying himself on the ukulele—he takes tickets at the door, where he can see people mosey around the gallery. “Younger kids, you hear them ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh,’ just fascinated by it,” he says. “It’s just a different visual experience than most people now are used to.”

Standing in that dark gallery, it is easy to imagine, for a moment, that one is perched on an alien landscape—the rim of an asteroid crater, maybe, or another planet’s moon—with looming celestial neighbors and stars all around.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook