Ground Truth

When Cameroon and Nigeria settled their long-standing border dispute, it was just the beginning. Then a 21st-century border had to be laid down.

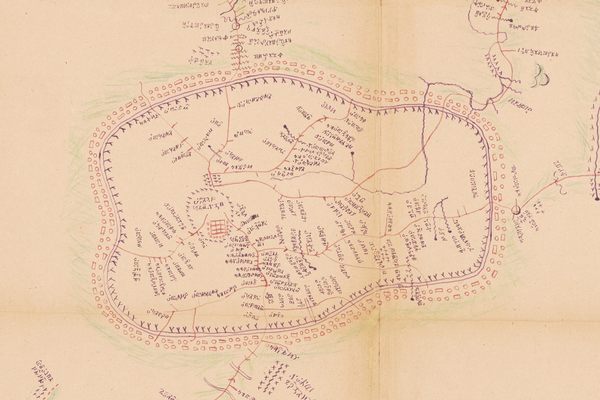

They talked about Ishmaelia. “No one knows if it’s got any minerals because no-one’s been to see. The map’s a complete joke,” Bannister explained. “The country has never been surveyed at all; half of it’s unexplored. Why, look here,” he took down a map from his shelves and opened it. “See this place, Laku. It’s marked as a town of some five thousand inhabitants, fifty miles north of Jacksonburg. Well, there has never been such a place. Laku is the Ishmaelite for ‘I don’t know’. When the boundary commission were trying to get through to the Soudan in 1898 they made a camp there and asked one of their boys the name of the hill, so as to record it in their log. He said ‘Laku’, and they’ve copied it from map to map ever since. —from Scoop, Evelyn Waugh, 1938

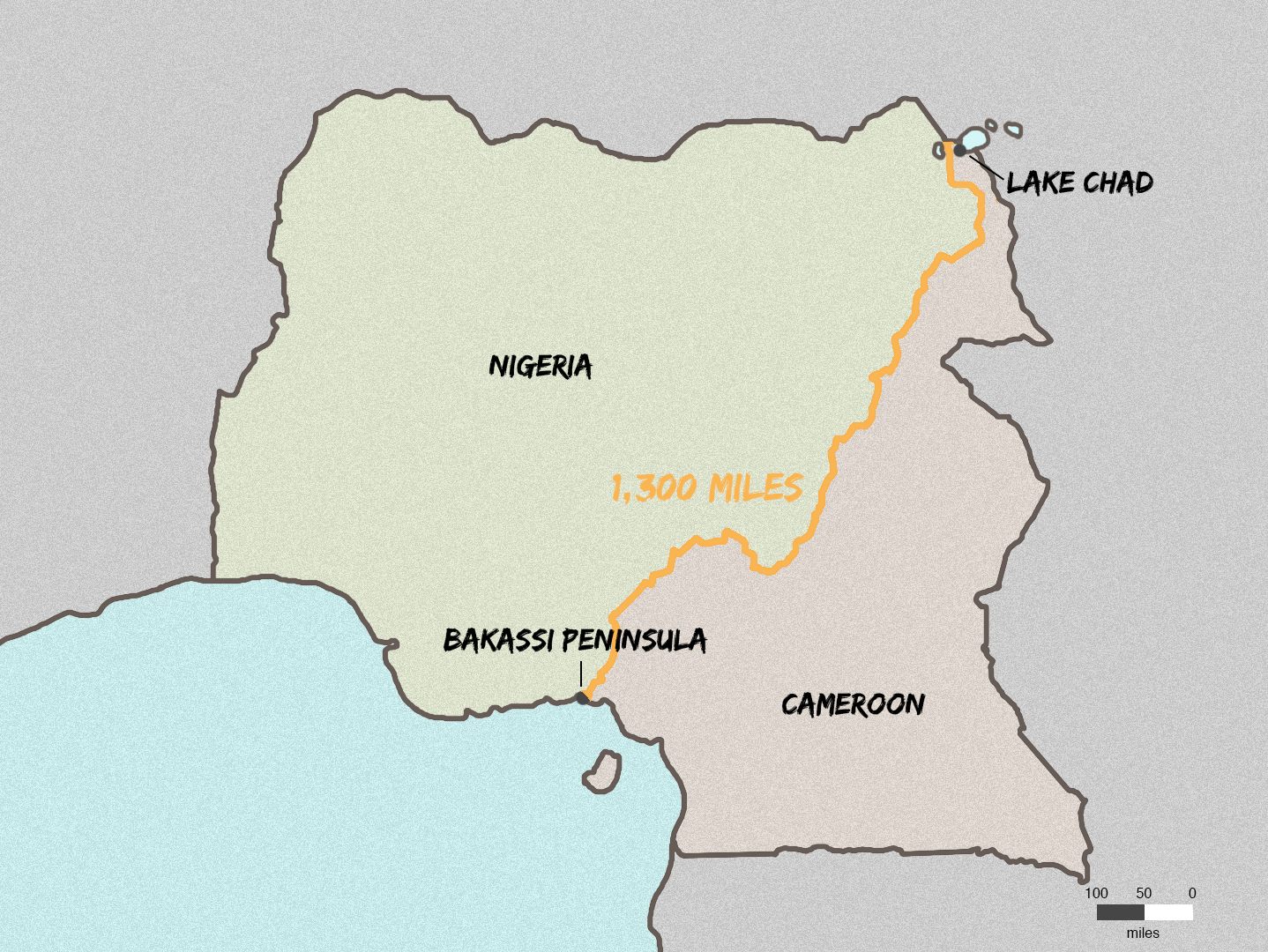

The trouble started between Nigeria and Cameroon in 1981, with the growing belief that the Bakassi Peninsula and the depths beyond it might harbor untold wealth in the form of oil reserves. Or rather, the trouble truly started a century before that, during what is now called the Scramble for Africa. It was November 1884 and representatives from 13 European nations, and the United States, got together at German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s Berlin residence to share cigars and divvy up a continent among themselves. During the following months, a collection of white men—most of whom had never set foot in Africa—split the continent into dozens of colonies that would eventually become more than 50 countries, sketching out borders using a strange alchemy of old maps, geographical landmarks, and collective avarice, with little or no regard for longstanding tribal boundaries or land-use practices.

Britain and Germany, who had been in a pissing match over where to draw the border between their coveted territories in West Africa, came to agree on “a line passing through Yola, on the Benoué, Dikoa, going up to the extremity of Lake Chad.” And that is, roughly, the story of how the border between Nigeria and Cameroon came to be. But that border was not real—it was rough, amorphous—and it wouldn’t be real for more than a century, well after the colonies became independent nations. How that happens, how a compromise dashed off on an old map becomes something else, a set of precise coordinates, concrete pillars that define a landscape, the governing geopolitical concept of modern statehood, is another story entirely.

There would be further agreements on the border, between Britain and Germany and later, after Germany’s defeat in World War I, between Britain and France. There would be some surveying, some mapping, and a general sense that a border had been fixed. For the purposes of the African colonial powers, it had been. But in the wake of African independence (1960 for both Nigeria and Cameroon) the previous borders lost legitimacy, given that the autonomous nations had never signed off on the described (and rather rough) colonial lines. And of course, one can argue, they never had been legitimate—or precise or adequate enough—in the first place.

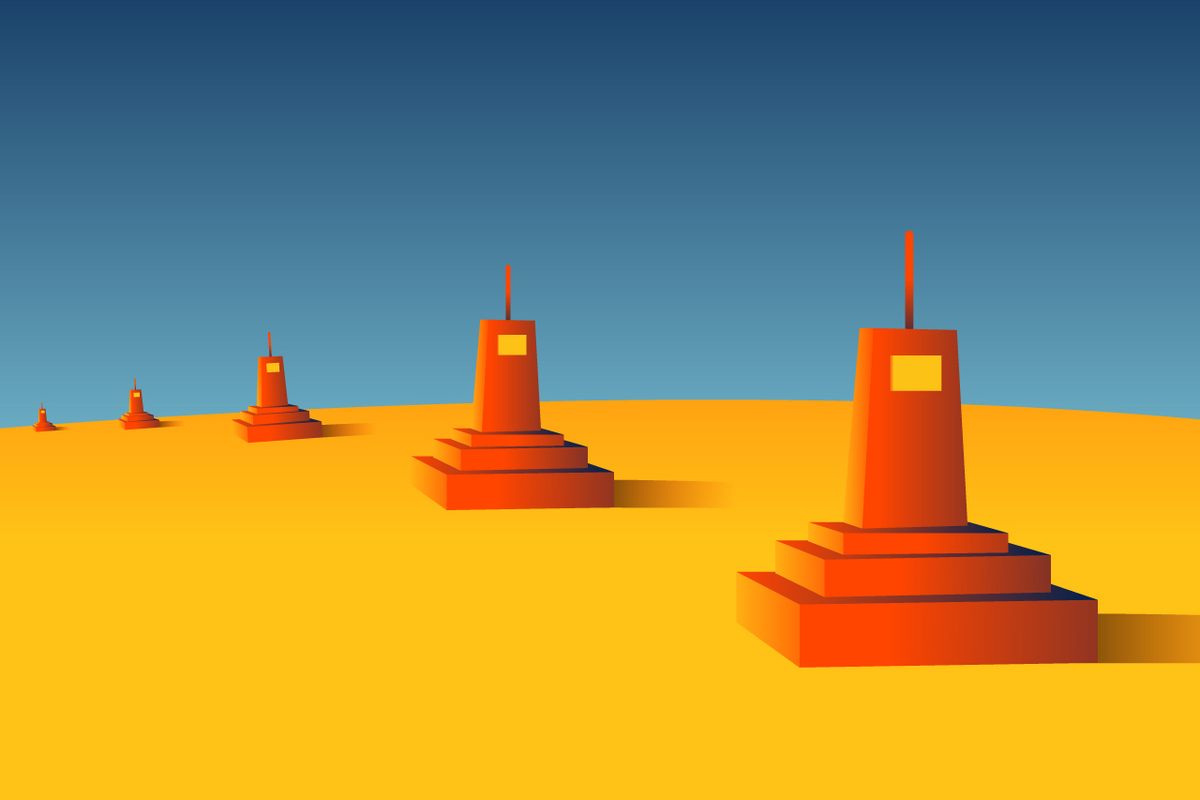

Today in sub-Saharan Africa, only one third of all borders have been delimited—the formal term meaning that they are properly fixed, that the countries on either side have agreed to the exact physical location of the border, and that the coordinates of that physical line have been thoroughly and accurately documented. That is what a border is, fundamentally. An agreement. They can be soft or hard, built on trust or enmity, between equals or prescribed by the powerful. Even fewer miles of border in Africa have been fully demarcated, meaning physically marked on the landscape, with reinforced concrete pillars of various heights and shapes anchored by underground footings. Of course, that is not so surprising. It can be extremely difficult to erect a pillar on a mountainside or within a mangrove swamp or in a warzone. They may not be needed, or worth the sweat, expense, and danger.

There are many reasons, too, for Africa’s lack of delimitation. In places where borders are both porous and somewhat ephemeral to the people who actually live near them, delimitation is less of a priority than, say, economic development, education, or safety. And there are cases in which it’s politically beneficial not to delimit a border at all.

“Sometimes vagueness is in everyone’s interest,” says Philip Steinberg, director of Durham University’s Centre for Borders Research (also known as IBRU based on its previous name, the International Boundaries Research Unit). Steinberg, an American, describes his interests as focused on, “the historical, ongoing, and, at times, imaginary projection of social power onto spaces whose geophysical and geographic characteristics make them resistant to state territorialization,” which is as good a reminder as any that the entire notion of borders is nothing if not complex, contingent, and downright fluky.

“If you’ve got two countries that are kind of getting along OK and they agreed to disagree, it can just create unnecessary tension,” Steinberg says of delimitation. “Diplomacy is filled with sort of agree-to-disagree, ‘don’t ask–don’t tell,’ arrangements like that… Of course, that’s not our image of the border, you know, the fence and the border guard.”

In the case of Cameroon and Nigeria, “agree-to-disagree” had been working to some extent. Their border stretches from the increasingly dry Lake Chad Basin in the north, through desert lowlands, up over the Mandara Mountains and their needle-like rock spires, between wildlife-rich Faro Reserve in Cameroon and Gashaka-Gumti National Park in Nigeria, then veers northwest to follow the Donga River, and back south into the dense rainforests of the Cross River National Park (Nigeria) and Korup National Park (Cameroon), before sliding into the Cross River itself. If there is a place where this ambivalence breaks down, it is over sovereignty of the last bit, the Bakassi Peninsula, a 400-square-mile wedge-heeled boot that juts tentatively into the Gulf of Guinea. Over time, both countries have claimed the Bakassi, and the potential resources off its coast, as their own. Summits between the countries in the 1970s produced declarations that placed Bakassi in Cameroon, but the Cameroonian government maintained a fairly hands-off approach to the region, whose inhabitants were primarily Nigerians who made their living in the fishing industry.

By the early 1980s, oil accounted for 90 percent of Nigeria’s revenue and, to some extent, its place on the world stage. In May 1981, its interest in the Bakassi region led to action. Nigerian military patrols traded fire with Cameroonian forces in the peninsula. That, along with a dispute over the Lake Chad Basin, nearly brought the two countries to war. Cooler heads prevailed for a time but in 1994 bloody clashes on the peninsula killed 34. That was when Cameroon’s president, Paul Biya, decided to do something fairly unprecedented: He appealed to the United Nation’s judicial arm, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, to settle the question of sovereignty over the peninsula, which would include a determination of the maritime border. Two months later, Cameroon amended its request, asking after the disputed Lake Chad Basin as well, and while the court was at it, could it please definitively outline the entire border between Cameroon and Nigeria once and for all.

For the first few years, the ICJ wrangled with jurisdiction and claims and counter-claims about which historical documents or unofficial practices would inform the law. In 1999, Equatorial Guinea entered the fray to stake a claim on some of the maritime real estate. Documents and arguments were presented and dissected in minute, sometimes excruciating, sometimes snippy detail.

A document from April 2002, Comments of the Federal Republic of Nigeria on the answers to the Judges’ Questions submitted by Cameroon on 10 March 2002, gives a sense of how subjective and confounding it all was. “Cameroon states that from Point V, the boundary as described in the Thomson Marchand Declaration follows the course of the El Beid (Ebeji) River,” one of the Nigerian comments noted. “This is an impossibility. Point V is not the mouth of the Ebeji, nor does it lie on that river, or any other river.” Another states: “Cameroon appears to be alleging that the 1946 Order in Council boundary is shown on Moisel’s map of 1913. This is clearly a ridiculous assertion. The draftsmen of the 1946 Order in Council used the words ‘an unnamed tributary of the River Akbang (Heboro on sheet E of Moisel’s map on scale 1/300,000).’”

Countless lawyers and country officials and a forest of documents dropped into the maw of this process until, finally, on October 10, 2002, on the basis of Anglo-German agreements from 1913, the court officially gave sovereignty of Bakassi to Cameroon. Using those and other colonial documents, particularly the Thomson-Marchand Declaration of 1931—as well as some horse-trading—the court decided where the entirety of the border would lie. But the judgment was still just a rough outline: a description of a border using latitude and longitude, and natural markers such as mountains and rivers, to get the general idea across. The real, hands-dirty, on-the-ground work would soon kick off back in Africa. It’s like the difference between deciding to cycle across the United States and then actually going on the damn ride.

In September 2002, a month before the ICJ released its findings, then-Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan arranged a meeting of the nations’ presidents in Paris, where they agreed that they would respect and implement the findings, and participated in the kind of handshake photo-op that mediators always hope will create a legacy of good will. The handshake was, in many ways, the easy part.

The Nigerian government was, overall and not so surprisingly, very unhappy about Bakassi and the loss of its still-theoretical potential. Losing the peninsula in a specific, international way—for good—did not sit well. On the ground, however, it was the fishermen who truly couldn’t believe what they were hearing. Around 90 percent of the peninsula’s estimated population of 300,000 was Nigerian, and most of them made a living off the rich fishing grounds of the area, which is so crisscrossed with inlets, rivers, and creeks that it looks like the back of a very old person’s hand. In the course of the hearings, Cameroon had pledged to protect Nigerians living on Bakassi, but the residents themselves doubted Cameroon’s intentions, given past animosity. In fact, it would take another presidential summit, this time in Greentree, New York, in 2006, to fully hammer out the details of the handover.

Annan tapped Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, a Mauritanian diplomat who had worked on tricky African missions before, including as a Special United Nations Representative in Burundi during that county’s civil war, to head what became known as the Cameroon-Nigeria Mixed Commission (CNMC). The idea was that representatives from both countries would work with United Nations staff and private contractors to oversee the proceedings.

This was when the notion of the border left the realm of the abstract and crashed down on African turf, when an inexorable machine of measurement and mapping and marking, gassed up in a European courtroom, began to roll across hundreds of miles of land and the people who live there. After the handshake, people would be hurt and displaced, or reassigned nationalities. Some people who had believed all their lives that they were Cameroonian would now find themselves living in Nigeria, and vice versa.

Abdallah understood that the CNMC had to start by selling the idea of the delimitation to the people who would be most affected. Instead of requesting military peacekeepers to ensure a peaceful handover, Abdallah took the unusual step of asking the United Nations to provide observers—a sort of diplomatic dream team of lawyers, professors, military representatives, government officials—to go to the villages and reassure the population that they would be treated fairly and that their new sovereign governments would not just force them to the other side of the new border. And he decided to start in the north, leaving the hard part—Bakassi—until later.

None of this ever had to happen before because the border was so undetermined and imprecise. That’s the political advantage of leaving a border fuzzy—people need not be beholden to it. Sometimes it is fine to leave a line imaginary, but this one was going to be settled, and that would not happen without a little upheaval.

There was the local Cameroonian representative in Bourha Wango who lost his entire constituency when the border moved, much to the delight of his rivals. And the Boki tribespeople, who learned that a boundary pillar was supposed to be placed in the middle of a sacred forest. The Nigerian village of Danare 1 became 75 percent Cameroonian, resulting in the loss of critical grazing land. Villages were formally handed over from one country to another; as early as December 2003, Nigeria passed 32 Lake Chad Basin villages to Cameroon with so little fanfare that there is very little record of it at all. Administrative structures had to be dismantled or abandoned; customs and immigration services replaced. In some cases, people stayed where they were under the new sovereignty; in others, they chose—or were forced—to leave.

Etinyin Etim Okon Edet, (former) Paramount Ruler of Bakassi and chairman of Cross River State Traditional Rulers’ Council, describes how he and his fellow Nigerians on the Bakassi Peninsula initially believed the ICJ ruling to be a joke. The people of Bakassi had not been consulted. It was like, he told Nigerian daily The Punch, “Our heads had been shaved in our absence.” Also on Bakassi, Chief Etim Okon Ene, who now lives in an internally displaced persons camp, says that, in 2008, Cameroonian soldiers came to demand that he hand over control of his village—his ancestral home. He says that the border change stripped them of their heritage and dignity, in addition to the land. Today his village belongs to Cameroon and is abandoned. He says that homes and buildings were burned and the inhabitants violently forced to leave for not agreeing to submit to the Cameroonian government and become Cameroonian.

But the work of delimitation is ultimately not about people: It is about process. It is about signposts that say that this land here, though it may look the same, is different than that land there. It is an idea 1,300 miles long—the distance from New York to Havana—that has to be turned into a thing. It has taken years and hundreds of people—lawyers, diplomats, politicians at every level, tribal chiefs, surveyors, cartographers, geospatial engineers, construction workers, laborers, security guards. Even now, nearly 17 years after the ICJ judgment, the work is not complete.

Of course, the land doesn’t know and doesn’t care. In geologic terms, this line is meaningless. But once countries have agreed to delimit a border, they have kickstarted a quest for accuracy that cannot and will not be compromised. The line must be discovered. The line must be recorded and those recordings must be very, very correct, and then the process is not going to stop until there is an official scar on the continent.

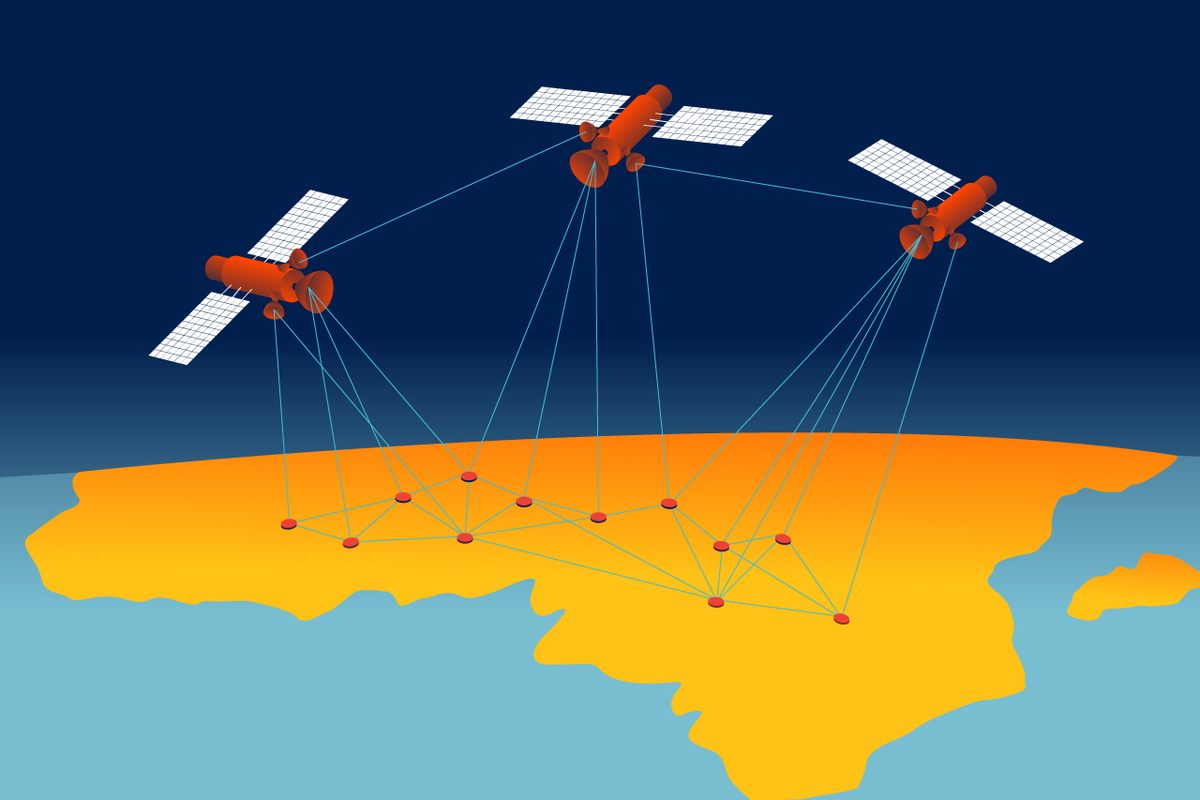

The advent of the Global Positioning System, which became fully operational in 1995, has dramatically changed our ability to locate ourselves, or any given spot, on the planet. You would be right if you believe that it has revolutionized the modern mapping process. “GPS” is as commonplace and ubiquitous a term as “Kleenex,” “Xerox,” or “Google,” though like those it’s technically incorrect to use it to refer to every satellite mapping system. GPS is just the American version. At some point after 1995, other nations began to wonder: Wait, what if the Americans turned off their system? So they started developing their own. Now there is the Global Navigation Satellite System or GNSS, which refers to a number of satellite constellations including GLONASS, the Russian system; Galileo, European; and BeiDou, Chinese. All told, there are more than 100 satellites orbiting our planet, continually transmitting blips at the speed of light. Your GPS device (even most GNSS users refer to satellite navigation as GPS) receives these packets of data and calculates how far away it is from a satellite based on the amount of time the information took to get to it. When it has information from at least four satellites at a time (and it pretty much always does) it can pinpoint where you are based on the difference in the data’s arrival time. This is known as trilateration, even though four satellites are needed to ensure precision.

This technical capability might suggest that delimiting a border should be a simple task, but the problem is that there is accuracy and there is Accuracy. GPS is not infallible. Satellites may not be completely correct and, as IBRU director Steinberg points out, data are open to interpretation. When it comes to delimiting a border, good enough is not good enough.

Peter Merrett was in his 20s and working as a civil engineer in the United Kingdom for a big firm that specialized in tunnels when he realized he needed a change. The work was both tedious and taxing. He saw how his 45-year-old manager was super-stressed and getting a divorce. Merrett fled that future and found a job with a company conducting oil exploration in Libya. Before he knew it, he was bouncing across the Sahara in a Land Rover. He had found the sort of job he wanted to be doing the rest of his life.

When Merrett returned home, he got married and started his own business, first providing survey services to local architectural firms and then later, with a business partner, doing international survey work. Merrett is attracted to geology and geography, but he also has the disposition for bringing meticulous method to adventurous endeavor. “I’m a bit pedantic about things. Accuracy is… good,” he says in a way that makes it abundantly clear that inaccuracy is very… bad. In 2005, his company, Merrett Survey, put in a bid with the United Nations to work on the Nigeria-Cameroon border and it was accepted.

Merrett Survey was not, however, hired to work on the border itself. Before true delimitation can be done, you need to establish a network of highly accurate geodetic control points, known as survey stations, whose coordinates are so precise that they then can act as the primary fixed points from which all other measurements are made. These can vary in how they look, but typically involve an underground concrete block, about three feet square, that secures a ground-level metal plaque containing reference information about the station, as well as a mark that a surveyor can use to line up either the plumb bob of his old-school level or his GNSS receiver. (If you start paying attention, you may notice similar survey plaques embedded in sidewalks or on mountaintops.)

For all their precision, the survey stations are fundamentally arbitrary. They can be almost anywhere, so long as we know precisely where that anywhere is. The number of them and distance between them vary from project to project, based on needs. Merrett and his team were tasked with installing 10 primary stations (five in each country) and 20 secondary stations (10 in each country), which could be between about six and 40 miles from the border. They began their work in 2007. Four surveyors from his firm—Merrett himself was not there for the duration—also trained Cameroonian and Nigerian surveyors in their methods, as part of the contract with the CNMC. On any given day, the group woke up in a small guesthouse or home allocated by a local chief and split into four teams—two on either side of the border. Each team filled a convoy of pick-up trucks filled with GNSS equipment, concrete, concrete mixers, surveyors, laborers, and country representatives. Two teams went ahead to approve locations and scout for construction materials, while the other two followed behind to dig a hole, pour concrete, and affix the critical plaque.

The CNMC and country representatives had chosen sites for the stations in advance, often inside a local chief’s or administrative office’s compound so that the markers would be relatively undisturbed and unnoticed. That these control markers are frequently, of necessity, in the middle of nowhere is both a problem and a benefit. Isolation offers protection, but there are times when someone stumbles across a marker and decides that it must mean that there is something of value buried underneath. So, logically, that person decides to dig it up. What they find embedded in the concrete beneath the plaque is a metal reference pin in the same horizontal line as the marker itself. Its sole purpose is to act as a backup to the marker on the station’s plaque, though of course the pin, too, might get dug up. During a project in Nepal, Merrett and his team went by helicopter to the top of a mountain to use a previously established control marker as a survey point. The marker—including its substantial cement footing—was missing and they soon found it in the local farmer’s wall. He offered to give it back, but of course it’s not the marker that matters, it’s what it marks: a spot that says, “This is the exact place you are on Earth.”

Obtaining that accuracy isn’t easy. After Merrett and his team built all their markers, they returned to the United Kingdom for a few weeks, for the Christmas holiday, but also to give the concrete time to set and settle so it wouldn’t move after they obtained coordinates of the spots. That’s the first step in obtaining precision on the scale of hundreds of miles: making sure that nothing changes, even a little bit. The next step we might consider more probabilistic, the product of repetition and rigor.

When they returned, the teams had to go to four stations simultaneously, two in each country, and take coordinated observations from the control marks for 24 hours straight. They were measuring differential GNSS—the difference in position between point A and point B (and C and D)—over and over. Your car’s GPS, when it’s working properly, has an accuracy of between three and 30 feet. When a company such as Merrett Survey takes on a job, the level of precision is specified by contract. The CNMC contract stipulated that the coordinates of the survey stations must be precise to within 50 millimeters, or less than two inches. The more accurate and precise the control point, the more accurate and precise the border coordinates. The margin of error between Cameroon and Nigeria, more or less, was the length of your thumb.

To get this accuracy, each team set its GNSS receiver over a survey station and attached it to several car batteries to ensure a continuous supply of power. They were using Leica dual frequency GNSS, which is sort of the hot-blooded thoroughbred to the stubborn donkey that is your phone’s GPS. The activity tended to gather interest from locals. Occasionally crowds formed with plenty of questions for the surveyors about what they were doing and how it all worked. The surveyors didn’t stay with the equipment for the whole 24 hours, but hired local guards to keep an eye on things. Theft was less a concern than overactive curiosity. If anyone touched or, god forbid, moved the GNSS, they would have to start all over.

“All work with GPS is an exercise in statistics,” Merrett explains. (Like almost everyone, he defaults to GPS when referring to GNSS.) “The software is working out the most probable answer, trying to get an accurate distance to each satellite, all 20,200 kilometers away and moving at 14,000 kilometers per hour, and then using that to compute the 3D difference in position to the other three survey stations occupied at the same time, to an accuracy better than 50 millimeters. So, the more data you have, the better chance you have of getting the right answer.” The true location of any given point on Earth, for measurement purposes, is a dot at the center of a cloud.

While Merrett’s team was putting in control points, another group had already begun taking initial steps toward delimitation. Delimitation is not a one-off job. It is a process of several steps, each with the aim of increasing both accuracy and precision. First came the ICJ’s rough description. Next a team assessed where that line became a reality, including choosing sites for future boundary pillar points. That line would be documented and mapped and then, later, fine-tuned towards absolute precision using Merrett’s controls.

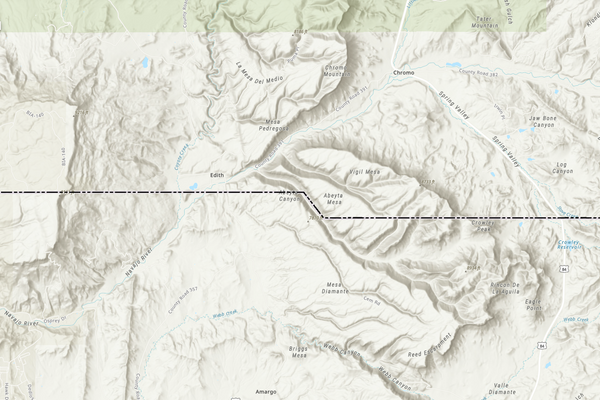

Starting in 2005, a Joint Technical Team consisting of the Geospatial Information System Officers who are full-time staff members of the United Nations, along with delegates from Nigeria and Cameroon, all of whom are technical experts, formally trained as civil engineers, surveyors, or cartographers set out to begin the assessment. The UN cartographic department in New York used satellite imaging to create 131 map sheets at a scale of 1:50,000 that showed a rough outline of the border as described in the ICJ’s findings. The team’s job was to traverse the length of the entire border—using jeeps, motorbikes, helicopters, and even canoes—armed with these maps plus the old colonial maps and treaties and descriptions of ancient German border pillars. (Abdallah says that the German reputation for engineering is reflected in the fact that their colonial pillars survived better than those made by the French and British.) The goal was to find spots for future border pillars that could ensure the permanence of the entire project.

Some of the descriptions from old documents but preserved in the final ruling were vague at best and unhelpful at worst: something like, “a hundred feet east of the largest tree west of the village,” says Merrett, who had spoken with surveyors working on the technical team. It was as much a matter of diplomacy and history and instinct—even art—as it was science. The assessment was done in stages, from north to south, through deserts, over mountains, in rain forests. At every point, both countries’ officials needed to be in agreement. Occasionally, in villages, residents would protest the line and that section would be set aside until it could be resolved higher up the political chain. That is one reason that, to this day, around 60 miles remain undelimited—places where the two sides have yet to agree.

Imagine, for a moment, trudging around some mountain on a scorcher of a day. Your only guidance is the following directive: “The Court accordingly concludes, first, that paragraphs 35 and 36 of the Thomson-Marchand Declaration must be interpreted as providing for the boundary to pass over Hosere Bila, which it has identified as the ‘south peak of the Alantika Mountains’ referred to in paragraph 35, and then from that point along the River Leinde and the River Sassiri ‘as far as the confluence with the first stream coming from the Balakossa Range’.” Having parsed and agreed upon what this might actually mean, the team would record its coordinates using a differential GPS instrument accurate to about three feet. Those coordinates would be sent back to the CNMC headquarters in Dakar, Senegal, where GIS officers would plot them in mapping software to create a record that continues to be updated and honed and fine-tuned to this day. The coordinates were subject to political approval and then, later, survey teams would use Merrett’s control points to ramp the precision ever higher. So it took history, law, diplomacy, and linguistic decoding to find a spot and then science and engineering to fix it in the world.

Next up came demarcation—a projected 2,696 concrete pillars. The CNMC had decided that pillars should be placed at 500-meter intervals in open country and 100-meter intervals in villages and towns (that’s about three and 16 per mile, respectively). None were needed for areas where rivers denote the border. Most would be rectangular cuboids 20 inches tall, with a buried concrete footing, but every five kilometers (three miles or so) would be “primary pillars,” obelisks poking 6.5 feet high. Borders are many things, including, eventually, a form of highly regimented land art.

Sani Nuhu worked on the CNMC in 2009 and 2010, as a project manager for the placement and construction of boundary pillars in a section of the border toward the north, after winning the contract from the United Nations. As a Nigerian surveyor, he was used to working in difficult geographical areas and this was no exception. His Toyota Tundra pickup bounced along through scrubland as he followed his GNSS to the general site of the next proposed pillar. Behind him was a small convoy carrying about 40 men: diggers, brick layers, cement pourers, metal workers, country representatives (always the country representatives), and the critical security detail. For Nuhu, the hardest part of the job was the constant fear of rough terrain and bandits. He says that because Cameroon and Nigeria had a relatively robust cross-border trade, there were a lot of very desperate people looking to steal the goods moving back and forth. Nuhu believes the bandits he worried about during his pillar construction contract eventually joined the ranks of the terrorist group Boko Haram, which has made much of the northern border area even more dangerous.

Because of the bandits, Nuhu informed his workers that when they bought supplies in a local town, they should always ask to buy on credit, and he regularly refused to pay the workers in cash. That way word would get around that the visitors didn’t have cash, and everything could be settled later. Nuhu also made a point of dressing in plain, worn clothes so he wouldn’t stand out as the boss and a possible target for kidnapping. He was not wrong to be afraid. On January 31, 2017, an armed group attacked a demarcation team near the Cameroonian town of Kontcha, killing five. The United Nations has since increased the amount of security it provides to such teams.

Generally, though, villagers were happy when the demarcation convoy came to town, because it brought a boost in commerce. Nuhu and his team stayed for a while at a hotel in the town of Waza and their bill provided the hotel’s owners with enough money to replace all their air conditioners.

In addition to the bandits, the pillar team had the terrain and weather to deal with, in no particular order: mountains, waterways, overgrowth, unpaved roads, heavy rains, and more. That was why it was so important to have those representatives of both countries on each team. Sometimes they needed to agree on a spot that was very close to, but not on, the delimited coordinate. Those representatives also needed to sign off on every phase of the pillar construction. This became even trickier in towns, where the border might run right through a building. The town of Banki, Nuhu says, is still missing some of its border pillars because the countries could never come to terms on what accommodations should be made to avoid going straight through a school and other buildings. These days, the residents of Banki have more to worry about than pillar placement, as it is the site of ongoing attacks by Boko Haram, as well as a growing camp of refugees fleeing, mainly, the terrorist group.

Since demarcation began in December 2009, 1,326 pillars have been put up—around half the expected total. Work has been slowed or halted over time for security reasons, to accommodate the rainy season, and regime changes, though Merrett says he saw that the United Nations just awarded a contract for another push of pillar construction. Merrett believes that the sort of border you decide to have is really a matter of trust. When he was working on the Cameroon-Nigeria border, a local surveyor asked him what sort of border pillars are used to mark the separation between England, Scotland, and Wales. Merrett said there are no pillars. Everyone just uses a map and trusts what it says. The surveyor was astounded. He felt physical markers were essential to make sure both countries were being held to their mutual agreements. Maps, after all, are not the real world. Merrett also says that his firm gets calls all the time about boundary disputes between neighbors. His firm tries to avoid that work. It’s never really about figuring out where the fence used to be, it’s about the people, about tracking a decay in trust. It’s easier to deal with Cameroon and Nigeria.

The CNMC is still active, currently chaired by Ghanaian special representative Mohamed Ibn Chambas, which is a testament to just how hard it is to delimit and demarcate any border, especially one that can be as remote and dangerous as the Cameroon-Nigeria line often is. The project won’t be over until demarcation is completed and final mapping and a “boundary statement” are developed using Merrett’s control points to record the most accurate coordinates of the pillars. The original estimate for the work was $12 million, with Nigeria and Cameroon each contributing $3 million, Britain and the European Commission kicking in a further $1.4 million, and the United Nations covering the rest. It’s not clear where the budget stands now but the project has taken, to date, 17 years, required countless man-hours, and contributed to the displacement of thousands. Despite this—in particular the upending of lives on the Bakassi Peninsula—the ICJ ruling and the CNMC have generally been considered a success internationally: The countries never went to war. The boundary, when all is said and done, will be a model for the kind of accuracy a modern border can have. Sadly, when you delimit an international border, there will always be people who get screwed. On the other hand, it can halt bloody, ongoing disputes by giving people one less thing to fight about.

This is why, in 2007, the African Union launched the African Union Border Programme to help increase the number of delimited borders. Most of the work that Steinberg and the staff of IBRU conducts is made up of training sessions to help countries around the world work on these issues. They do three or four a year, where they teach civil servants—primarily midlevel foreign ministry officials—the basics of boundary research and settlement. The trainings occupy this strange overlap of law and international geography. Instructors include lawyers, surveyors, and political geographers such as Steinberg. Recently, they held one in Addis Ababa, in partnership with Germany’s international development agency, GIZ (which is also providing support to the African Union Border Programme), dealing with river boundaries in Africa. The idea is that the officials at the training will learn enough to share with other members of their governments. “If there’s a conflict brewing,” says Steinberg, “somebody needs to become an expert really fast.” They often get people from countries with boundary disputes at a single training session. This gets tricky when they do practical exercises, which might involve dividing into two teams and formulating legal arguments and maps to decide, say, the boundaries around islands off a coast. They’ve learned that they have to use imaginary countries and geography because otherwise a benign exercise can go sideways quickly.

Merrett’s firm has worked in 61 countries and every continent except Antarctica, but it’s become hard for his firm to get work overseas for the simple reason that most countries increasingly have highly qualified surveyors of their own. Merrett sees this as a good thing (his company has aided in IBRU training sessions) and of course, it is. African borders were born of outsiders drawing lines that they had no business drawing. Those lines created countries and conflicts, divided people arbitrarily and made strange bedfellows. Now those countries are taking ownership of the lines and the hard decisions that accompany them, even if, sometimes, they have to call in the rest of the world to broker the handshake. Perhaps the main job of delimitation in Africa and other places is to finally exorcize the ghosts of those colonialist European boundaries. One measurement at a time.

Additional reporting for this story was provided by Victoria Uwemedimo.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook