How the ‘Queen of Thieves’ Conned French Riviera Wealthy

The cat burglar and fake countess swindled and stole her way through La Belle Époque.

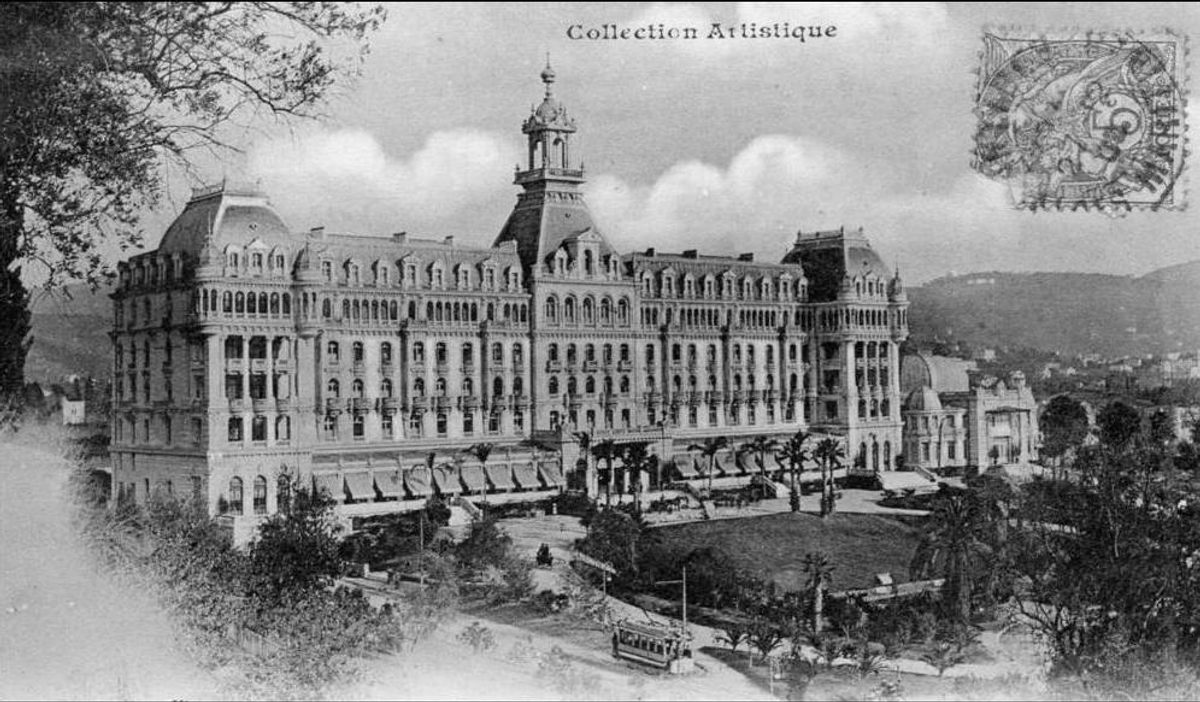

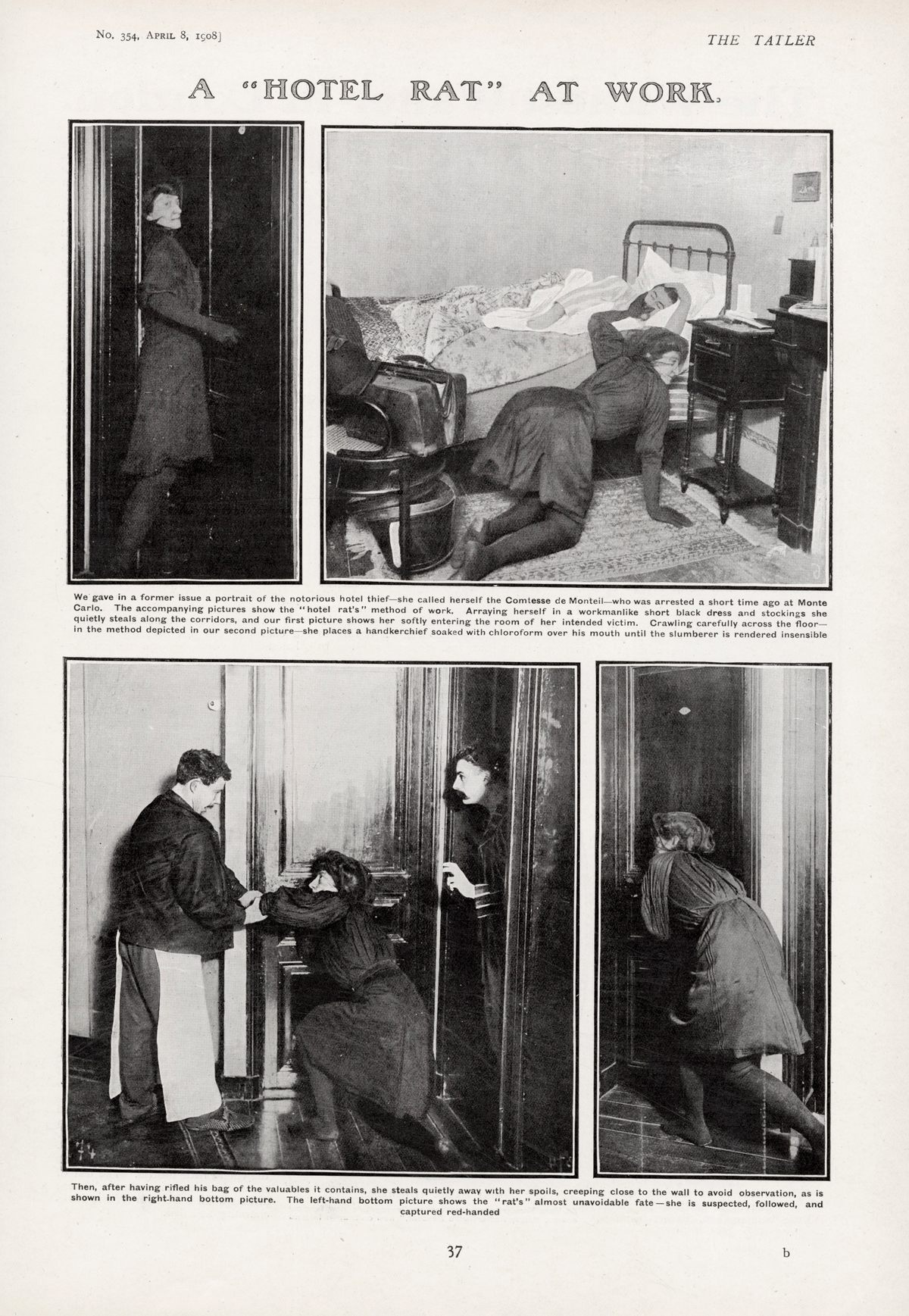

In the predawn hours of March 8, 1908, Nice’s famed Promenade des Anglais, bustling during the day, was quiet. So too were the corridors of the Hôtel Impérial nearby. Down one plush hallway, a woman in black moved noiselessly in felt-soled shoes, melting into the shadows. She wore a black veil that shrouded her features, and carried a set of silver lockpicks. After years of pursuit, French police were about to catch the so-called Comtesse de Monteil in the act. The “pseudocomtesse,” as newspapers dubbed her, was a jewel thief, cat burglar, and con artist, as well as the alleged leader of a ring of thieves that stretched across the Mediterranean’s most opulent tourist destinations.

The capture of the Comtesse de Monteil was an immediate media sensation, making international headlines. Reports emphasized her beauty and cunning, calling her “The Spider” and “Queen of Thieves.” Exhaustive coverage detailed her lavish lace evening gowns and state-of-the-art luggage, which transformed into a full-size armoire. It’s no surprise that the arrest, and most of her crimes, took place in Nice, one of the most famous cities of the Côte d’Azur, which includes the principality of Monaco and French Riviera, “a sunny place for shady people,” as novelist W. Somerset Maugham called it. For a jewel thief and con artist, the atmosphere at the time would have been irresistible, full of wealthy marks attracted by the area’s popularity with royals—Queen Victoria visited nine times—and the casino at Monaco’s Monte Carlo. During this period, casinos were banned in several neighboring countries, and Monte Carlo created “this ethos for elite people to aspire to, which is not only are you able to move freely, but by doing so you are able to flout the laws of your home country,” says Mark Braude, historian and author of Making Monte Carlo: A History of Speculation and Spectacle. “And that’s not seen as dishonorable, that’s seen as enviable. And glamorous.”

The glamour of the Côte d’Azur was a far cry from where the future queen of thieves, born Amélie Condemine, grew up. Her father was a butcher in the rural town of Mâcon, in the Saône-et-Loire region of Central France, which is chiefly known for its vineyards. At 18, she married Ulysses Portal, a wine merchant 14 years her senior, and the couple moved to Paris. Little is known about this period of her life, but the press reported that, after ten years of marriage, the couple separated and she moved to the United States. The only clues to her activities there are photographs police later found among her belongings, which showed her in the company of New York’s elite—and even aloft in a hot air balloon—according to news reports. In 1888, she returned to France, calling herself the Comtesse de Monteil.

She lived in a Paris apartment for part of the year, but apparently restricted her criminal activity to locales associated with elegant leisure travel: Geneva, Alexandria, Monte Carlo, and, chiefly, the towns of the French Riviera. At the time, French nobility were a “very closed society,” says Caroline Weber, a historian at Barnard College who studies French society during the Belle Époque. The pseudocomtesse risked giving herself away “just by not knowing how to pronounce a particular name,” Weber says. The aristocracy rarely visited the Riviera during this period, so she could execute her deception undetected. In fact, hoteliers and wealthy foreign tourists welcomed the Comtesse de Monteil, delighted to host a supposed member of the elite who deigned to rub elbows with them.

By 1892, the Comtesse de Monteil had come to the attention of the French police due to strangely coincidental thefts at hotels where she was a guest. Despite that, this stylish swindler continued to operate around the Mediterranean for another sixteen years before her arrest. She reportedly controlled a group of thieves who took on similarly grand identities, posing as an Italian diplomat or the son of a wealthy shipowner. While staying in a hotel or traveling on a steamship, she would observe fellow travelers and calculate their value as targets—a notebook detailing her assessments was discovered in a search of her Paris apartment following her arrest. In the wee hours of the morning, she would break into her target’s hotel room, pocket their valuables, and then slip out again, entirely undetected. At trial, none of the jewels in her possession were identified as stolen, suggesting that she and her network of thieves worked with underground jewelers who would either buy the stolen goods or place the gems in new settings unrecognizable to their owners.

After her arrest, the comtesse became something of a folk hero in the media. Newspapers emphasized her pluck and daring, such as when she robbed the same Swiss banker three times. The third time, he awoke and raised the alarm, but she sprinted back to her room, where she pretended to be asleep and was never suspected. On another occasion, in Alexandria, the hotel accused her and an accomplice of theft; the pair fought the accusation in court and won a defamation suit against the hotel. While she was a criminal conning the wealthy, she was also portrayed as a woman of the people. Le Petit Parisien noted that her maid liked and respected her, and that she was a generous tipper.

Income inequality in turn-of-the-century France may have colored her image. “It seems like every time society is in a state of economic crisis and flux, the burglar suddenly becomes this iconic, glamorous villain character,” says historian Eloise Moss. “I think it acts as a really important political commentary, a dissatisfaction with economic inequality, and also a way of imagining yourself into a different, more illicit, adventurous lifestyle.”

The pseudocomtesse never confessed to her crimes, insisting throughout her trial that her jewels and money were gifts from a Spanish grandee and an Egyptian pasha, among others. After being convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison, she slipped out of public consciousness and back into the shadows. Although records confirm that she was released from prison in 1918, her fate is unknown. The once-grand Hôtel Impérial where she practiced her craft, and was finally arrested, is now a public high school.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook