Destroyed by Fire in 1849, Canada’s First Parliament Building Gives Up Its Secrets

Odor control was a significant concern.

The story of the building that housed Canada’s first provincial parliament is one of political turmoil, fire—and odor management.

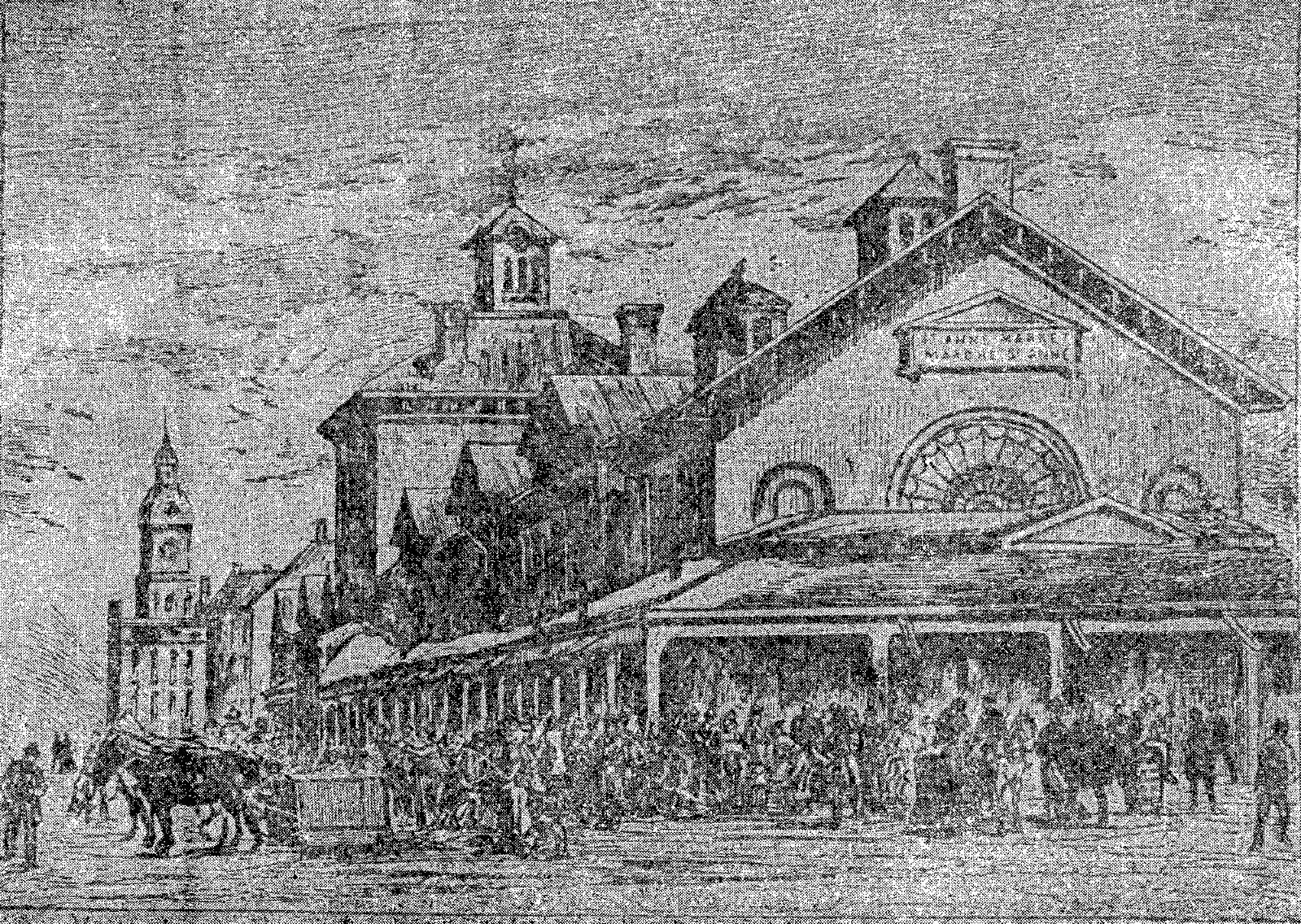

The structure was originally built between 1832 and 1834 to host the city’s first indoor market. St. Anne’s Market, as it was known, was also one of the first public structures in North America with an enclosed sewer beneath it. “Back in the mid-1800s, Montreal’s rapid population growth was putting pressure on the nearby Saint Pierre River, which basically became an open-sky sewage,” says Hendrik Van Gijseghem, Archaeology Project Manager at Montreal Pointe-à-Callière Museum, which has been leading archaeological investigations at the site of the parliament building over the last several years.

Concerns about health risks from the river—at the time the miasma theory, which posited that diseases such as cholera could be carried by “bad air,” held sway—led Montreal’s government to channel part of the river into a collector sewer under the new, 330-foot-long Georgian building. “It was, at the time, an extraordinary feat of civil engineering,” says Van Gijseghem.

After 10 years as a produce market, the building was converted to host the Province of Canada’s first unified parliament, in 1844. Five years later, on the night of April 25, 1849, it burned to the ground.

At the time, politics there were dominated by fierce debate over whether Canada was to be autonomous or remain a British colony. It was as polarized as could be, and following the passage of a controversial piece of legislation, loyalist rioters burned the building down.

A new market was built at the site after the fire, but it was destroyed in 1901 and later turned into a parking lot, though the sewer remained functional until 1989. This infrastructure kept the site sealed and undisturbed for decades. Archaeologists started to unearth the site once the sewer was closed off, but the big finds came starting in 2011, when a team led by Louise Pothier, an archaeologist and curator at the Pointe-à-Callière Museum, discovered the “spectacularly well preserved” foundations of the building, along with a trove of artifacts from its last moments as the seat of Canada’s provincial government.

“Urban archeology usually deals with trash, objects that appear in a scattered way after they have been thrown away,” says Van Gijseghem. “In this case objects were left in their context of use, because people had to leave quickly during a fire.” The unusual fate of the building—burned then sealed away, created the “perfect archaeological conditions.”

The collection of artifacts includes tobacco pipes, liquor bottles, glasses, and oyster shells. Other notable discoveries are dozens of burned books that were, counterintuitively, preserved by the fire, carbonized like scrolls found in Herculaneum after the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Two very rare sealing stamps also survived, one from the legislative assembly and one from the council library. The stamp that bears the seal of the legislative assembly is so far the only known surviving example. What’s particularly exciting about this find is that Pothier and her team also found, on an online auction site, a letter bearing the seal that had been sent to Britain just a week before the fire. “It was a really magical moment,” says Van Gijseghem. “I was sitting by my computer, holding the stamp in one hand and looking at a screen displaying a letter that had been sealed with that same seal 170 years ago.”

Though it’s known that the fire was caused by rioters, its exact cause is a mystery. The fact that these items were left probably exactly where they had been used suggests the fire was “quick and violent.” Historical accounts of the igniting incident vary. One theory is that it was accidental, caused by a thrown brick that knocked over a gas lamp. But last summer, Montreal’s Grey Nuns, housed across the street from the site, examined their archives and found a previously undisclosed account of that night that mentions “maniacal mobs, armed with sticks and torches, purposefully setting fire to all corners of the building, even adding accelerant and fuel.” But there are enough contradictions in the various accounts to make the exact events hard to pin down.

Another group of finds, and perhaps the most unexpected, has to do with the reasons for the construction of the building’s sewer in the first place—fighting odors.

Van Gijseghem calls it a “fantastic collection of Victorian-era sumptuosity,” including personal hygiene items. “We found soap dishes, toothbrushes, balm, perfume containers, shoe polish, all of which we did not expect, as it was mostly men who used the premises,” he says. These finds suggest that lawmakers spent a lot of time in parliament and had to freshen up from time to time.

They also show that upper-middle-class Victorians were very concerned about odors, and this, as much as its central place in Canadian history, thematically defines the building. “First it gets built out of worries of bad odor causing disease, then we find all of these hygienic products, it actually got us wonder about the actual smell of the building back then. After all, it was built on top of a sewer,” says Van Gijseghem. “But we haven’t found any written account. For now, it’s only pure speculation.” Smell, it turns out, is a powerful trigger for memory.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook